Alice Guareschi is a visual artist based in Milan.

Yuri Ancarani, Ravenna 1972, lives and works in Milan, Italy. He is represented by Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin and ZERO…, Milano. Yuri Ancarani is an Italian video artist and filmmaker. His works come from a continuous mingling of documentary cinema and contemporary art, and are the result of a research aimed to explore regions which are not very visible in the daily life, realities in which the artist delves in first person.

Yuri Ancarani: Actually, there were three complementary exhibitions: Bologna, Milan, and just before that the retrospective at the Kunstverein in Hannover, which had a different configuration but also featured many videos and films. The two Italian exhibitions were almost simultaneous because museum programs had been pushed forward due to the pandemic: an inconvenience, however, that turned into an interesting and simultaneously very dangerous opportunity, because there were thousands of square meters to set up and give meaning to. I found myself having to create a dialogue with the spaces, whereas often those who work with videos or films only have to deal with a rectangular screen. And it is by looking at the spaces that these two very different projects were born, precisely because the situations were different. The space at MAMbo in Bologna is almost claustrophobic, even though it is much larger, and there the path related to Atlantide unfolds. Not only the film, but also a lot of extra material created during the shooting, because with the technique of video-making you don’t always only shoot what you have decided to shoot: if I saw something happening that I thought was interesting, and a bit magical, I would take the camera and shoot it.

AG: In your vocabulary, do you call your way of working “video-making technique”?

YA: The quintessential video-making technique is still that of Dziga Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera from 1929, although 16 mm cameras were used then, with all the problems associated with time management. Video-making allows you to move very lightly and record infinite times: with a digital camera today you can shoot the same footage at zero costs, you can record at the same time you’re watching the real thing, without the fear of not having enough film available… So yes, it is very similar to the 16 mm camera that was used in the early days—however, video-making as I understand it is also something more, it is something really new, because you know that you can aspire to producing great images as well. In fact, video has always had these same characteristics, but it has always been confined to very small devices, like monitors or low-quality video projections, whereas today it is completely different: you can make a real film using this technique.

AG: I am curious about your definition. What this type of practice means is very clear to me, I have experienced it directly in my work, and we can find its theoretical roots in experimental cinema, in Astruc’s idea of caméra-stylo—in short, let’s go back to the 1950s, if not earlier. I am interested in understanding how you define your way of working precisely at the lexical level… That’s why I emphasized the expression “video-making”: I was curious about your choice. There is a direct relationship with time that opens itself up to improvisation, to change, to the unplanned, and to the unexpected.

YA: It is also possible to work on several materials at once: in the Bologna exhibition, for example, there were videos that I shot and edited even though I knew they would not make it into the film, but I had in mind that I would realize a project related to Venice sooner or later. The sort of things that you can store away in the drawer, because they will find their time and place on their own, like it happened in this instance. Then, of course, compared to experimental cinema, today cameras are different: they record at 8K and can film at night, with only moonlight. These possibilities used to be science fiction, and today they allowed me to shoot some key scenes in Atlantide.

AG: We can say that the Bologna exhibition starts from a film, Atlantide, and articulates around it, holding it as its central core. It becomes almost an explosion of the film, if I can use this image: it draws towards its center and connects things that were around, before and after the film, or that maybe were excluded from it. As if to broaden the field of vision, of the experience of what then you see in the film. While the Milan exhibition seems to me to have more of a classical structure, like a retrospective, since practically all of your film works are presented. Perhaps some are missing, but the main ones are there and are installed almost all on their own, in dedicated spaces. Besides the inconvenience of the benches, that I found a bit punitive, you can watch them in small, specially set up, projection rooms…

YA: Benches give you a dignified position for the enjoyment of an art work. I don’t like to see people in museums sinking into poufs. Better to stand sitting with a straight back, or on the floor.

AG: It depends on how your back is…

YA: Benches force you to keep your back straight, on axis, with your head slightly raised: like in church.

AG: Exactly, stretching the spine, like during yoga. However, moving on from this detail, we can say that you have recreated isolated environments, also on a sound level, and that this allows for a so-called focused and frontal view of the work.

YA: I started from the assumption that no one wants to see a video exhibition. No one, despite the fact that everyone now spends their time in front of some screen. The exhibition Lascia stare i sogni was based precisely on this. You had to have the feeling that you could leave at any time: if you wanted to go in and watch a video you could, but it was your choice, not an obligatory step of a predesigned path, and this in my opinion was the strength of this exhibition.

AG: So you also considered the possibility that people would not enter the individual rooms?

YA: One can do whatever they want. They are even free to not go to the cinema, nobody has any kind of obligation. And it is precisely because of this clear idea that the exhibition went well. People ended up going in, and once inside they watched everything. The moment you enter a room, you are eaten up, devoured by the moving images, and it is difficult for you to get out afterwards: you begin out of curiosity and end up watching the whole film. But at the same time, it was very important for the space to be bright and not oppressive. The PAC is incredibly bright and that’s how it had to stay: it’s very different from MAMbo and, as I said, I wanted the spaces to participate in the dialogue. Atlantide is my latest film, but when I think about these two exhibitions my filmography actually should be looked at in reverse. It is as if Atlantide is the first episode of a research I’ve been conducting for a long time, a research on male behavior in all its forms and which, despite being a man myself, I really struggle to understand. I observe men, I have learned to look at all their facets, exploring personal dimensions or investigating workplaces. Atlantide is a first “reverse” episode because it starts from observing boys, in the crucial moment when they become adult men: it is still crucial today to educate young males in a different way than the current one, which forces them to be successful at all costs, and instead often causes irreparable personal and social damage. In this backward path we go back to Il Capo (The Boss), which chronologically is my first film, where a grown man has completed his path marked by strength and almost violence, and indeed is proud to destroy a mountain.

AG: Was this intention somehow clear and recognized by you from the beginning? Or is it an awareness that you matured after accumulating a series of works, that is, did you find this fil rouge between the various works, between the different films, at a later point?

YA: An example of how I conduct my projects are the Ricordi per moderni (Memories for moderns) videos: now I present them all together and they seem incredibly coherent, but in fact I shot them over a very dilated time, over almost ten years: I had no explicit plans to put them together, nor did I explicitly want them to follow a specific theme. But, when I presented them for the first time in an exhibition at the Marino Marini Museum, we decided to bring them together: it was an experiment, trying to bring out the great coherence that I myself was discovering in those videos that I had shot individually, sometimes unconsciously. I realized at that moment that even when I was working intuitively, I was actually already following my own line.

AG: In a sense, do you not think that what holds them back together is the title, and therefore the cut you give, the point of view through which you present again, or present for the first time, these fragments?

YA: The title is yet another level of reading an art work, and in an art work there are many levels of reading. Sometimes the title is a decision of the curators.

AG: I’m talking about the title Ricordi per moderni…

YA: To explain the title Ricordi per moderni, I must tell you an anecdote that is dear to me. Many years ago I happened to meet Fulvio Panzeri, the curator of Pier Vittorio Tondelli’s literary works. At that time, he was working on a publication titled Rimini, where he collected stories, fragments and memories of Pier Vittorio’s trip to the Riviera. Fulvio invited me to participate in a group exhibition curated by him, titled Sei di speranza (Six of hopes). He was one of the first people who believed in me—we’re talking about a long time ago, and it was perhaps one of the first exhibitions I participated in. On that occasion he told me, “In a completely different way, using another language, you are carrying on the narrative of the Riviera as Tondelli did.” The title Ricordi per moderni came precisely from a newspaper article that appeared in that collection. This story is little-known and very personal: the meeting with Fulvio Panzeri was very important to me, and I think his passing was a great loss.

AG: He paid you an extraordinary compliment, I would say…

YA: At first I did not grasp his insight, but then I realized that he had been right. He had also asked me for stills from my videos to include in this publication. At the time I had shot only three, I was just starting out, and I wondered, “What do my videos have to do with it?”. He had already figured it all out, while I still didn’t know that those videos had taken—or were taking—their own path.

AG: Before I interrupted you, you were talking about the title of the exhibition at PAC.

YA: The title of the Milan exhibition is a curatorial decision that I found very intriguing, because it almost ironically reversed the reasoning I had made when I shot Atlantide. In the film, in a conversation between the two young protagonists, Daniele scolds Maila for her “bad habit,” that of having too many dreams: “Now,” Daniele tells her, “forget about dreams”. When the two break up, Maila confesses that she has stopped having dreams: but considering that she is only sixteen years old, this statement is chilling, the trauma is very strong. The theme of dreams has been explored and interpreted by Diego Sileo and Iolanda Ratti in a very interesting perspective: it highlights that we are living in an age in which entertainment operates in a devastating way on people’s psyche, almost worse than the privately-managed TV we have endured in Italy for so long. And since cinema is now pure entertainment, it is very complicated to make films d’auteur today, when we see so much overproduction of movies that you even start wondering how it’s possible for them to be produced.

AG: Then there’s Ghezzi’s film Gli ultimi giorni dell’umanità (The last days of humanity)… I don’t know if you’ve seen it, it just came out in theaters but it was presented at the Venice Film Festival last year. A film that clearly detonates this threat to pure entertainment in a three-hour long editing, with dirty, dilated, insistent frames, the use of voice-over…

YA: Our generation grew up with Enrico Ghezzi, we would skip school in the morning because we had been up at night watching his program Fuori orario. It was a great fortune, which protected us so much from commercial TV.

AG: Absolutely. And I find that this title, Gli ultimi giorni dell’umanità, is in line with what I mentioned before concerning Ricordi per Moderni. This is also a title that gives meaning to the images of the film; it’s as if it gave them meaning a priori, to the point that you can almost ignore their content. What I mean that the title ties the images together, and I think this observation also applies to the one you chose for your fragments, because in a sense it puts them in a very precise perspective. Offering a point of view, a perspective, it also gives them more strenght, don’t you think? But let’s get back to the exhibitions. You talked about the two spaces, MAMbo and PAC, which are two very different spaces, architecturally. As I said before, the exhibition in Milan is more classic, in a sense, because it allows the viewer to retrace your work linearly, but in reverse, as you said, in the sense that your intention is for it to be presented backwards. And yet the first video you see entering the exhibition space is Il Capo, which is from 2010, so if not the first, at least one of your first important jobs.

YA: Il Capo is the film that allowed me to travel around the world, and it was an important experience: with that film I went to Venice, then I traveled a lot, it opened many doors for me. If my audiovisual production was originally confined to classic electronic video-making devices, with that 15-minute film I entered the world of cinema. I remember being told, “Enjoy these moments, the life of a short film is fleeting” because film festivals always need novelty. But for me it was inconceivable to think that a short film must also be short lived, because as an artist you try to make things that last as long as possible, that live beyond the time in which they are shot.

AG: Il Capo seemed to me like the ouverture of the exhibition, its prologue. Together with the aforementioned Ricordi per moderni, it is one of the few works that are exhibited outside the individual rooms, visible even to those who do not intentionally choose to watch one of those other films. I am interested in the geography of the exhibition because not everyone who will read this interview has seen it, not everyone lives in Milan, so…

YA: Il Capo is at the beginning for several reasons. Firstly, it is considered my most important film, so for the curators it had to be seen first. For me it is also the film that nearly everyone must have seen a still, a trailer, or an edit of. So visitors immediately see images they already are familiar with, and even then they’re free to stop and watch the entire film or not. Ricordi per moderni, on the other hand, has a very strong visual impact in the space: visitors who want to continue watching can go down to the tank and watch the videos one after the other, and those who do not want to see them individually can watch them all together from a distance.

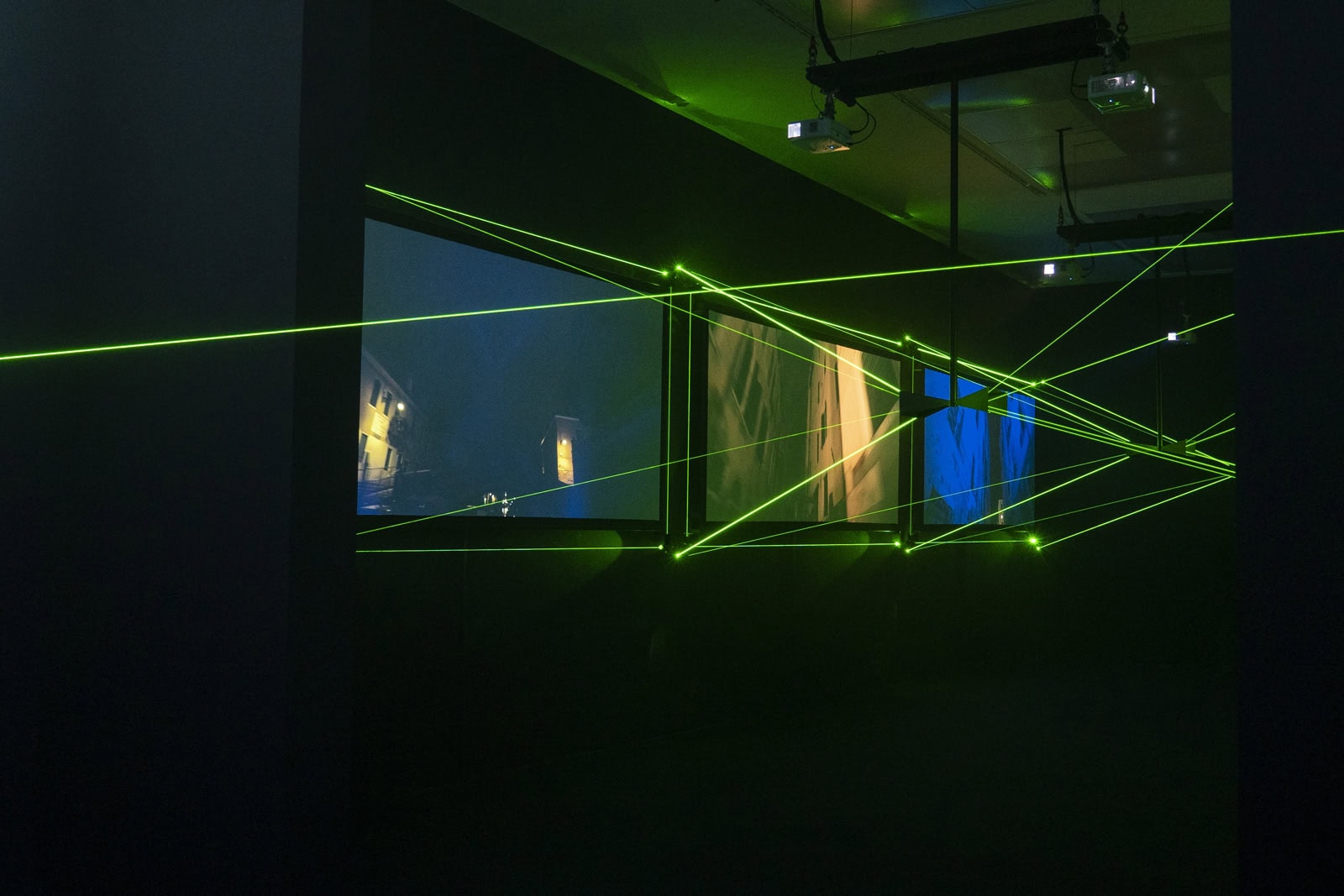

AG: The exhibition opens with this incipit, a reference to the beginning of your journey and precisely to a crucial turning point of your work. Then you enter the large hall, where there is a long sequence of screens displaying Ricordi per moderni, a strip that almost cover the big glass window overlooking the back garden. The window was darkened and turned into an extended LED wall, where the audio of the individual screens turns on alternately, without overlapping their sounds, right?

YA: The videos play the most iconic scenes in loop, and then randomly, from time to time, one of the videos is played entirely, so visitors will hear the sound of a random video. If they want to follow along they can, and then another will play, and another…

AG: Right, you turn on the sound of the video that is playing entirely, while the others continue to spin in loop. It is like a device with its own timing and internal rhythm, which ensures that the audios of the eight videos are never reproduced simultaneously, so don’t ovelap. This allows us to see a video in its entirety, with its sound, while continuing to have the perception of the others at the same time. Then there are all the other PAC rooms, which are closed off by red curtains, with a clear reference to the movie theatre.

YA: The red velvet curtain reminds of the entrance to movie theaters, but also of a theater stage. Each video is a performance in which theater and film can dialogue. And by lucky coincidence, the exhibition Lascia stare i sogni will move from PAC to a historic movie theater in Milan, Cinema Beltrade, where a red velvet curtain opens at each screening. In some way, Beltrade is our movie theater: once a small neighborhood theater, today it has become a landmark on the Italian scene.

AG: Yes, but not only that… I also think of other wonderful theaters in the world! However, visitors who choose to cross the threshold of one of the rooms immediately find themselves immersed in a rather dark space, and have the chance, helped by a timer at the entrance, to see the whole film from the beginning in a very classic viewing session, without interference from other images. And your work is also presented by series: Il Capo is indeed part of a trilogy.

YA: The first trilogy is called La malattia del ferro (The iron disease).

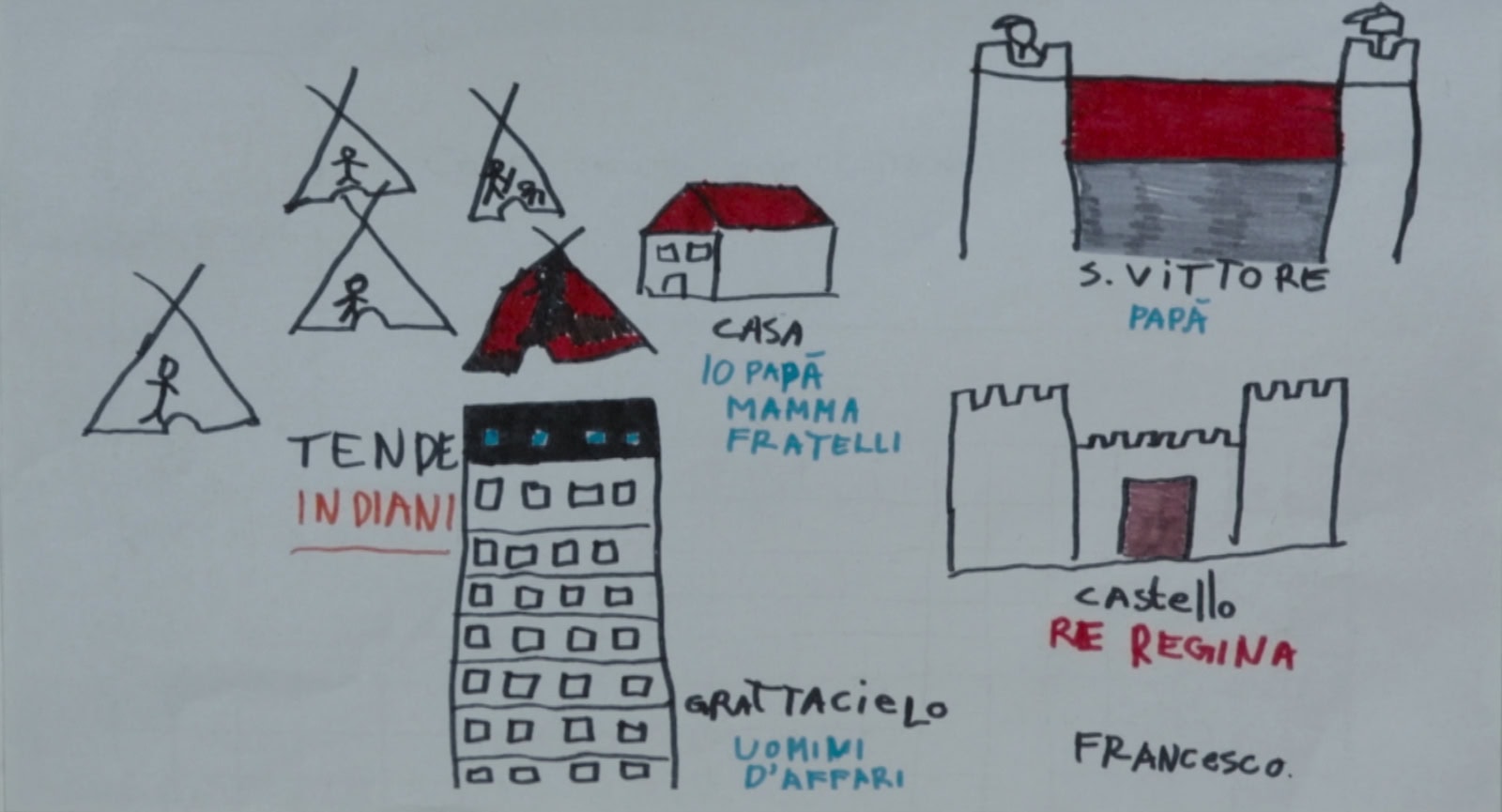

AG: This includes three works: Il Capo, Da Vinci and Piattaforma Luna (Moon platform). Then there is a second trilogy called Le radici della violenza (The roots of violence), which includes San Vittore, San Siro, and San Giorgio, films that have the names of three saints but refer to three iconic places of contemporary culture.

YA: The prison, the stadium and the bank.

AG: One thing that has struck me much—even concerning what you said before, namely your attention, observation and investigation of the male universe, with all its critical traits, question marks and shadows—is the presence of a work that has a completely different form from the others, on a filmic level. I am talking about the video you shot with Marina Valcarenghi, who is called Il popolo delle donne (The people of women). The most flagrant element is the binary view of the world, which highlights the differences between men and women. This is the only film in which there is a female protagonist, alone, and it is a person with a name and a surname, therefore with a declared identity, who speaks to the viewer, and even speaks for 50 minutes, while in all other films your male figures are almost masks, as they embody roles, dynamics, but do not have their own identity. Their personal stories remain completely off screen, sometimes even their bodies are dissected into details. They are protagonists only through gestures performed in function of something. It struck me how suddenly, in the course of the exhibition, a woman appears and takes the word for 50 minutes: it’s interesting to see the contrast that this creates, and the fact that in your body of works this gesture arrives in 2023.

YA: This is not the first time I have made a video of this kind: in Séance, from 2014, a psychic talks about art by invoking the spirit of Carlo Mollino. It is a séance, but it is also a monologue of about 30 minutes. In some ways, it’s a similar video, in others it is obviously very different, because the séance takes place in Mollino’s house and it’s an opportunity for a very refined investigation of the environment: after all, it’s not essential to know who is speaking.

AG: I remember seeing it years ago, don’t ask me where, but from a stylistic point of view, in my opinion it is more similar to your other works.

YA: There is a common element in the content: in all my films, the subjects are definitely dangerous places. The theme is also danger, the mythical test of a man facing danger, the idea of climbing higher and higher only to be taken lower and lower. The theme of Il popolo delle donne is also dangerous, and Marina is hypnotic, hypnotising: when I go into that room and she starts talking, I can’t get out myself. She talks for fifty minutes and you can’t stop listening to her: and what’s more, the one shown in the exhibition is only the short version, but I am working on an extended version of the film.

AG: Childhood memories: Edizioni dalla parte delle bambine, a wonderful italian publishing house releasing books between the 70s and 80s, which proposed a reversed look at the world from the point of view of the young girls, something rather exotic at the time. Marina Valcarenghi wrote Il pirata blu e altre storie (The blue pirate and other stories) which was one of my favorite books as a child, so for me, she is a figure from the distant past and it was very interesting to listen to her. But back to your film: from my point of view, filmically speaking, the main difference with your other works is precisely the fact that you find yourself in front of a character with a name and a story, who speaks about men, women, the relationship between the sexes, and even the collapse of the patriarchy, an architecture that has lasted for millennia and is now collapsing, with its violent aftermaths and its disjointed shocks.

YA: I felt the need to do something that was exactly the opposite of Atlantide, because in order to shoot that film, which is of fantastic nature despite dealing with real things, I got to know the young actors and I was confronted with an environment where culture is no longer a primary desire, no longer a goal to strive for. I confess that it was a disheartening revelation. I did not expect such a desert, and therefore I needed to see completely different faces: shooting Il popolo delle donne in the cloisters of the University of Milan also served as a cure, because I had been too long in touch with a really degrading subculture landscape into which I had to immerse myself for the sake of film. And also, in front of a challenging theme like gender-based violence, you have a duty to create a system that gives the viewer the maximum possibility of fruition: that’s why the plot is designed with great simplicity. For example, the beginning shows youngsters studying, meeting up, talking to each other, kissing. I really needed that, and I have to say that I am pleased with the way it offers an interpretation of the whole audiovisual landscape that surrounds it in the exhibition: it’s a well-executed contrast to exit the room of Il popolo delle donne and go into another room to watch The Challenge.

AG: Indeed, the counterpoint between these two registers is very interesting. The subjects change, but in general, there is a strong continuity in your work, precisely from a cinematic and even acoustic point of view: the presence of an unreal dimension within a totally real reality, that of a ritual and mystical dimension within the mechanical nature of repeated gestures, and then the sound that amplifies things and takes you in other directions, opens up to other times, dilated, which in this film instead are completely shut off. Here, there are few types of shots, more or less three distances from her and her face. The background, the cloister at the University of Milan, is a stationary scene, and this person speaks for 50 minutes, which never happens in other films.

YA: I was precisely looking for this effect: Il popolo delle donne and Séance are both masterful lessons, although in completely different ways. They really are two important lessons, I realize that I learned a lot: they were useful to me, and I share them.

AG: As I said before, I think they are very different from each other, as films… Anyway, returning to the exhibition space at PAC: there are all the various video viewing stations, and then on the second floor, on the balcony just above the line of screens displaying Ricordi per moderni, you have chosen to expose another tracking shot, that of the posters of all your films. A quiet hallway, where you have the opportunity to see the entirety of your work in a different form: in the form of posters. There are also two other rooms on the upper floor, with two more rather long films which may have deserved further isolation, namely The Challenge and Whipping Zombie.

YA: Although my films take you to another dimension and always make you feel like you are somewhere else, far away, in truth they are all shot in Italy, close to my home, close to my studio. Da Vinci, which looks like a sci-fi movie, was shot in Pisa; Piattaforma Luna was shot in the Adriatic Sea off the coast of Ravenna, which is my city. All my videos are related to places very close to me, around me. All except The Challenge and Whipping Zombie, which were a kind of personal challenge. These two films were shot around the same time, the former in what was then the richest country in the world, Qatar, and the latter in the poorest, earthquake-ravaged Haiti. Two completely different places, but on the same geographic parallel, gave me two very different films. By shooting them, I developed a growing interest in speed and movement, elements that are also central to Atlantide. The Challenge was cproduced first, I was interested in going there to see what the state of ‘cultural health’ was, and I saw some incredible displays of regression. Then came Whipping Zombie, which reflects on the presence of the past, on collective practices of processing of suffering derived from the slavery on the plantations of Haiti.

AG: This is interesting because it adds a geographical note to the exhibition map. I didn’t think of the fact that they were the only two films shot in very distant and very different places, and that’s why you chose to install them in a separate room.

YA: Since there is no dialogue, a lot of importance goes to the sound. The audio is the script of my films, it is what gives you the feeling of living that moment. This is why there was also the need to create rooms where you could keep a very high volume.

AG: To wrap up, a classic question: what are you working on now?

YA: I am working on an unusual project with the Santa Cecilia Orchestra in Rome. It is the opening of the theatrical season with a concert by Ottorino Respighi, who imagined places in Rome and wrote three themes: The fountains of Rome, Pines of Rome and Roman Festivities. I will go to all the places Respighi was inspired by, to interpret the images of his journey. It is a one-hour long film, very challenging, and the score will be performed live by the orchestra, of course. I will be an extra element of the concert. I am very curious to see what will come out of it.