In these times of low liquidity, many people in Italy are looking at the Milan-Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics as a potential flywheel. An event with two energy and urban poles between which there is, semi-secretly, a small third world, which, as befits every third world condition, collects desires, needs and hopes on a thin ridge: in this case on the slopes of Mount Antelao, the highest peak in the Dolomites. In 1956, while Cortina d’Ampezzo was preparing to host the first edition of the Italian (winter) Olympics, a few kilometres further down the valley, in Borca di Cadore, the ENI Residential Village was growing on a stony and steep terrain of about 200 hectares: a social and political experiment realised at the desire of Enrico Mattei, who was then ENI’s President and who followed its growth until his unexpected death in 1962 (due to an aeroplane accident, over the circumstances of which there is still a heavy black cloud today). The architectural and urban project, designed by Edoardo Gellner, includes a huge summer colony, a campsite with fixed tents, a church (designed in collaboration with Carlo Scarpa), two hotels and 280 single-family cottages, today mostly inhabited. At the moment, the Village seems to be suspended between the utopian aura of the original foundation project and the vibrant actions of the new artistic experimentation project, commissioned to Dolomiti Contemporanee, careful not to fall into determinist optimism or the self-referential rhetoric of abandonment.

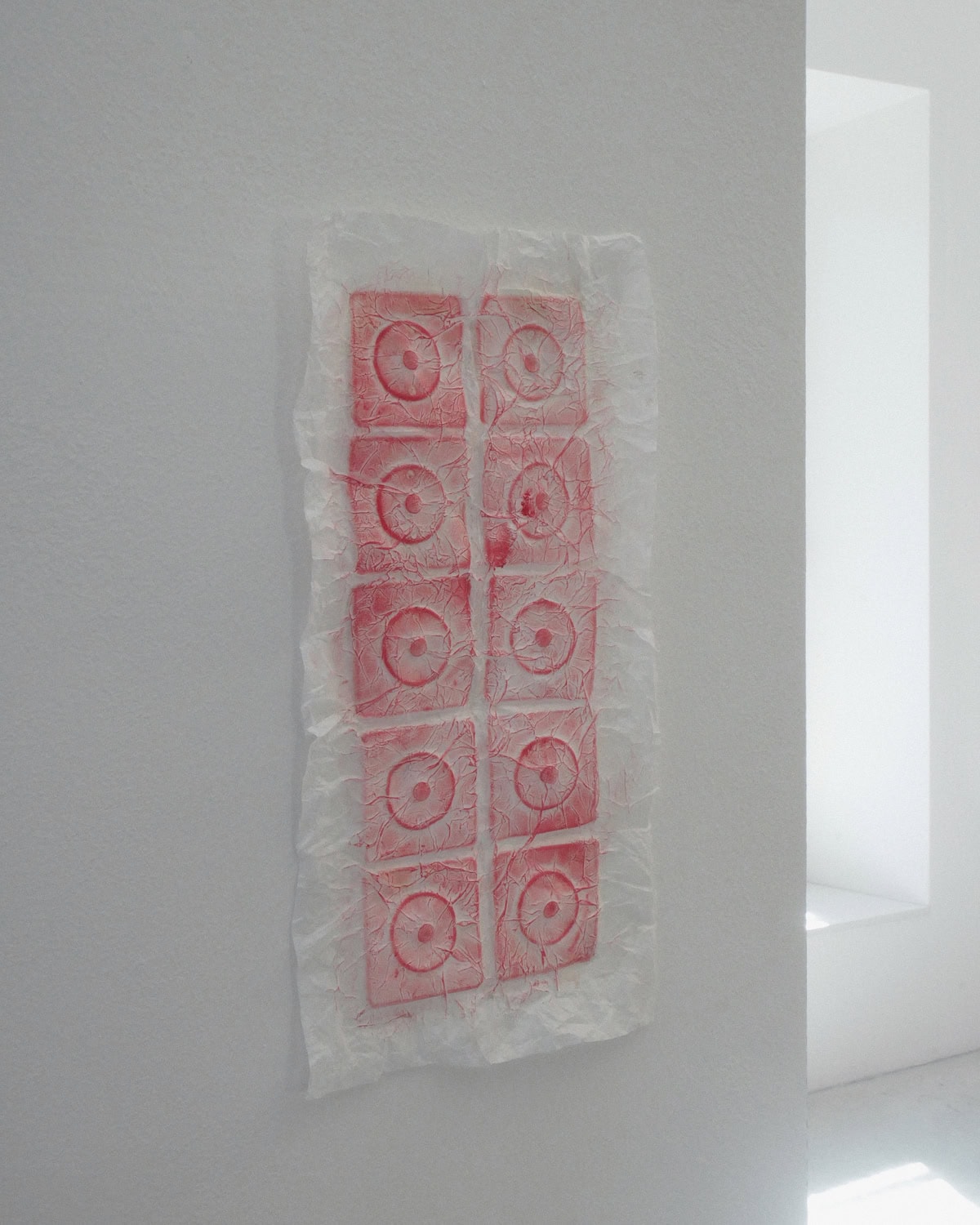

The opportunity to see the Village was given to me by an invitation to visit “Who Killed Bambi”: a collective art exhibition curated by Gianluca d’Incà Levis, Deus ex machina of Dolomiti Contemporanee, and hosted in Casso di Cadore, a village about 50 km from Borca. Acting as a connecting link between Borca and Casso, a clue: a tear in the landscape–a kind of chiselling–taken in the former location by a Veneto artist, Roberta Busato, and rolled up, like a primordial sleeping bag, to be transported further down the valley. An analytical operation, if it is true that the exhumation of that piece of soil and grass represents the first step of an investigation, a sort of “biopsy”, whose aim is to highlight the fragment’s transitory condition of “second nature”, having been previously exhumed from another context and replaced as the native soil and nature of the Village. We will therefore say second nature as the objectifying and primordial condition of art, thus recalling Hegel’s actuality (just for a moment) in order to leave behind the all too weak thought of the French third landscape, so dear in recent times to the chicest architects, even if ancien regime. If the negative trace left on the ground by Roberta Busato’s action may remind one of a burial (without a body), on the object level her “Prato a rotoli” offers the vision of a semi-living body, almost threatening, directed to the stomach like a piece of arte povera (with something more) and complicated to decipher like an object trouvé (with something less).

If the Village in Borca conveys suspended traces, the space in Casso welcomes visitors with a game of parts, in which the washed-out stones of the houses, an original 500 Sprint red car and the breaths of about twenty souls behind the shutters (including that of Luigina, who, if warned in advance, can offer hot soup) participate. The loss of innocence in the relationship with nature, heralded by the exhibition poster (a fawn with a bleeding hole in its forehead, which makes one think about Freud), assails us even before we enter the door of the former school overlooking the valley, striking us with the non-sense violence of a morphologically washed-out territory and a landscape as familiar as plastic surgery (the Vaiont dam is just a step away and the stuff still smells of dispersed energy, as it has for almost sixty years now). Once inside the exhibition space, the question arises again punctually: Who killed Bambi? Perhaps the hunters, who had already killed his mother. Or perhaps Bambi himself: a fawn that never lived, a symbol of a nature that is lost in its own representation. Seen in this way, the risk the project takes is remarkable: it may not be about the sex of angels but, at least implicitly, it prompts questions about the existence of an animal conscience. As punctual as the penguins of Madagascar, the lemmings of White Wilderness materialise in the mind, the documentary made by Disney a year before the release of Bambi in which–artfully constructed–he mother-scene of the “suicide” of a group of chubby rodents, with a collective leap from a high Antarctic cliff (actually, located in Manitoba) is famous. The myth of this ritual, constructed and performatively fuelled by the technicians of the Hollywood majors, has long distracted attention from the real significant fact. In the obsessive cartoonish vision of human-animal equality, the sense of their difference is lost, so well represented by the lemming: an extraordinary sensor of natural settlement limits, as opposed to man or other anthropised animals, such as boars or nutria.

Driven by the pressure of thousands of individuals running away from overpopulation, in their forced migrations, lemmings die en masse (usually by falling into cliffs or rivers). Where the chubby rodent transforms by its behaviour a limit of nature into the boundary between life and death, humans interpret this as a passage to be crossed, and create bridges and roads in order to found a new town or village on the next bank. In this way, in human and urban “dispersion”, every passage (between two worlds) is transformed into a landscape (a “third world”), according to a continuous design process of which art is the foundation: in Borca as in Casso, in Milan no less than in Cortina. At the time of the visit, the grass on the meadow was beginning to turn yellow, evidently due to a lack of water.