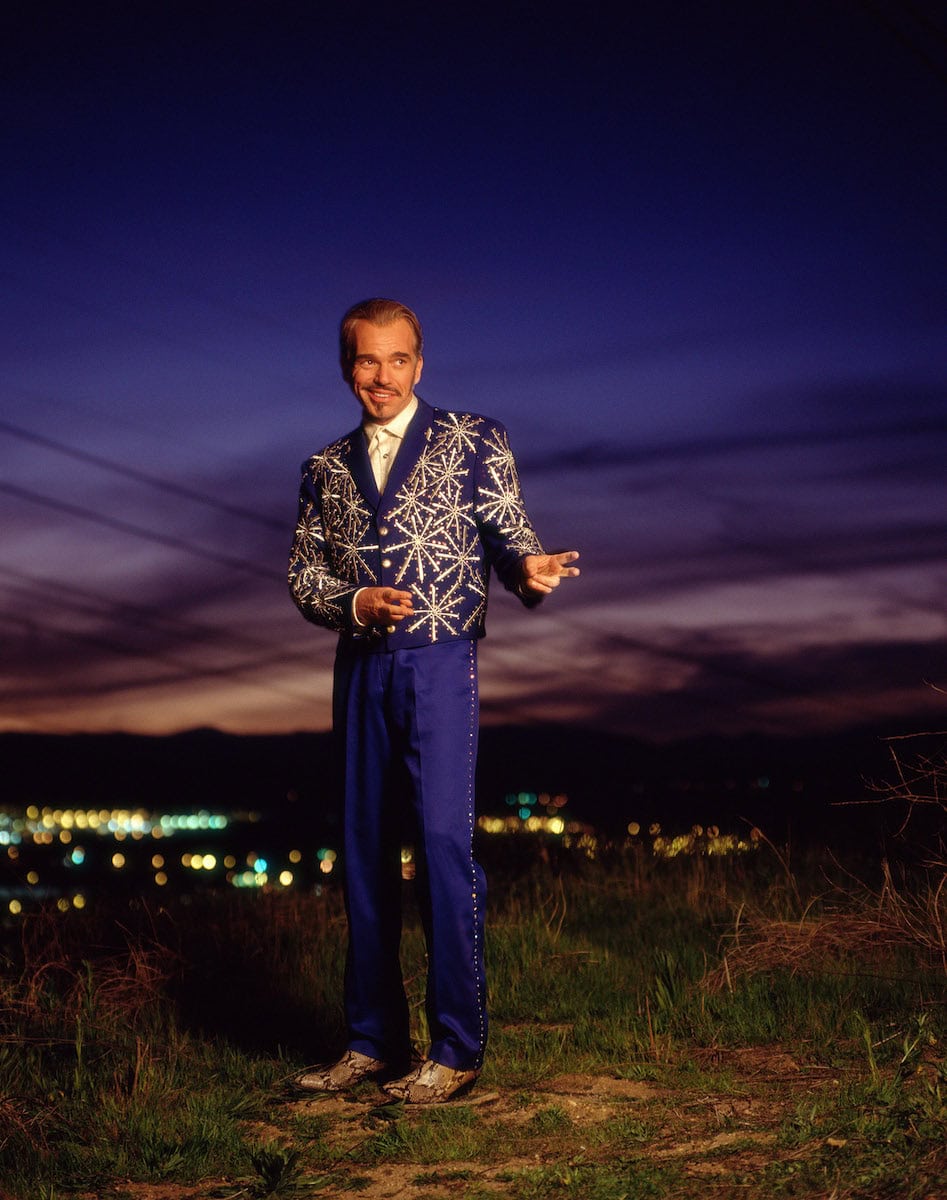

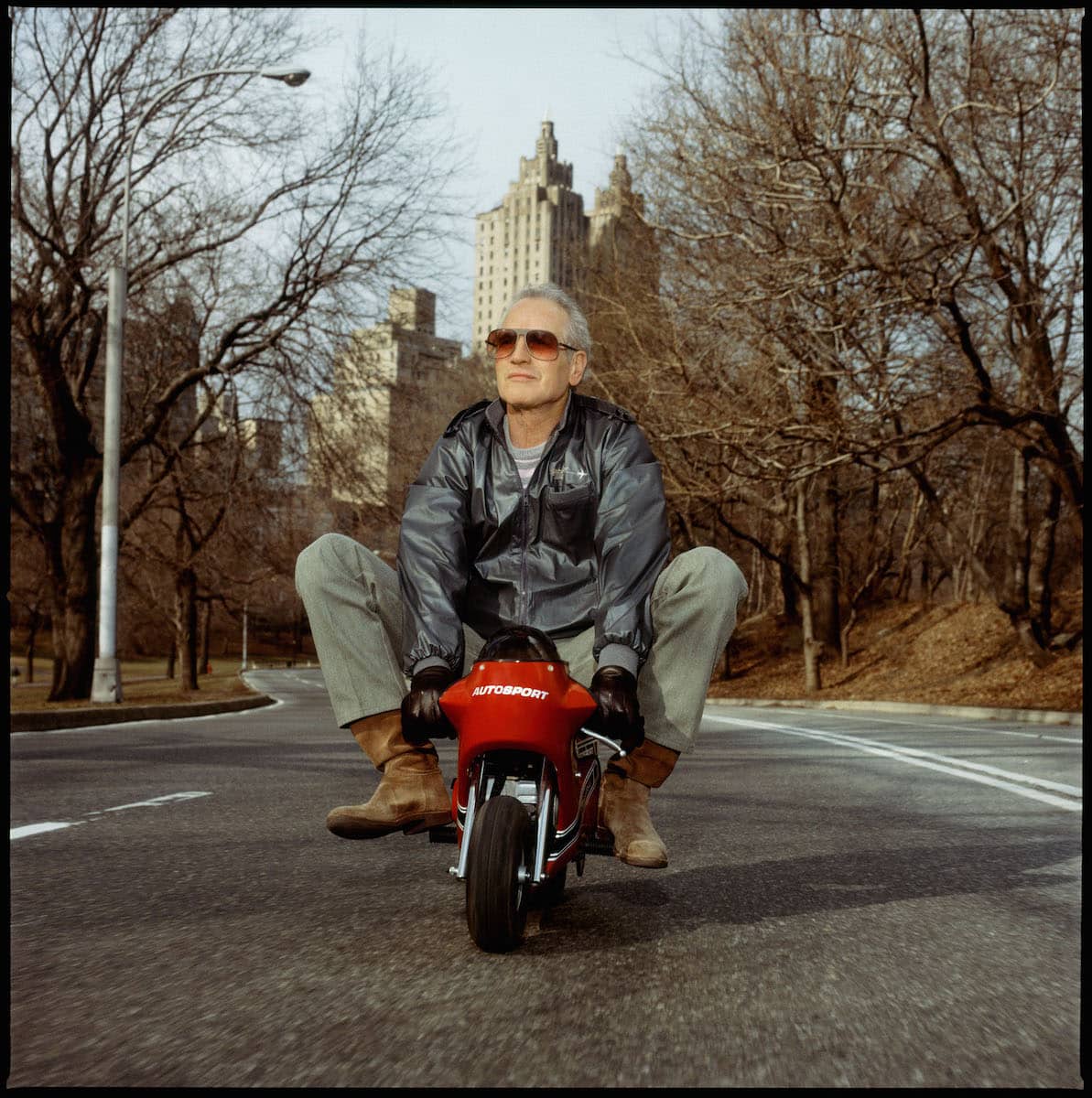

A nocturnal Los Angeles sets the backdrop. A space of freedom with uncertain boundaries yet clearly delineated by the cast shadows. Spiral staircases, entrance hallways, and streets to be mastered by the most diverse means, this is where the staging of a portrait begins: with deciding one’s set. The word ‘set’ is not used lightly when it comes to Timothy White, a photographer who has immortalised Hollywood’s greatest stars, capturing the final glory days of a generation of icons such as Audrey Hepburn, Shirley MacLaine, Paul Newman and Liz Taylor, and accompanying a new bunch of stars—perhaps the last to be so transgenerational, in a cinema that is becoming increasingly infantilised—such as Harrison Ford, Mel Gibson, Denzel Washington, Billy Bob Thorton, Bill Murray, Bruce Willis, Nicolas Cage, and Julia Roberts. The photographer seems to have a clear objective: render them immortal, eternalising them in their ‘aura’, a concept that is gradually fading away in today’s world of Hollywood.

The dichotomy of stardom was highlighted by French semiotician Edgar Morin, who interpreted the phenomenon (beginning in the 1910s and therefore strongly inherent to the rise of cinema) as oscillating between the symbolic level that these figures embodied, as though divine entities living in a new Olympus, and their transformation into objects of mass culture, something to be sold along with the catchy title of a film and used as merchandise rather than symbol. If rebelling against this concept meant clinging to the unconventional bodies of an intermediate generation (that of De Niro, Pacino and Hoffman), the 90s, on the other hand, with its cinema for all—engaging adolescents while elevating them in films that also appealed to their parents—saw a return to the actor not as a person, often even overtly political, but as a star: an entity that could embody new, easily recognisable social values. This return came with a new awareness (as do all successful comebacks) of the irony that characterises this generation. Two examples: Harrison Ford, the valiant and righteous actor of every self-respecting legal thriller, but equally the archaeologist-adventurer with whip and hat, who never fails to flash his winking smile; and Bruce Willis, the gruff strongman hero in a white tank top who can solve any extreme situation while delivering a lightning-fast joke at the same time.

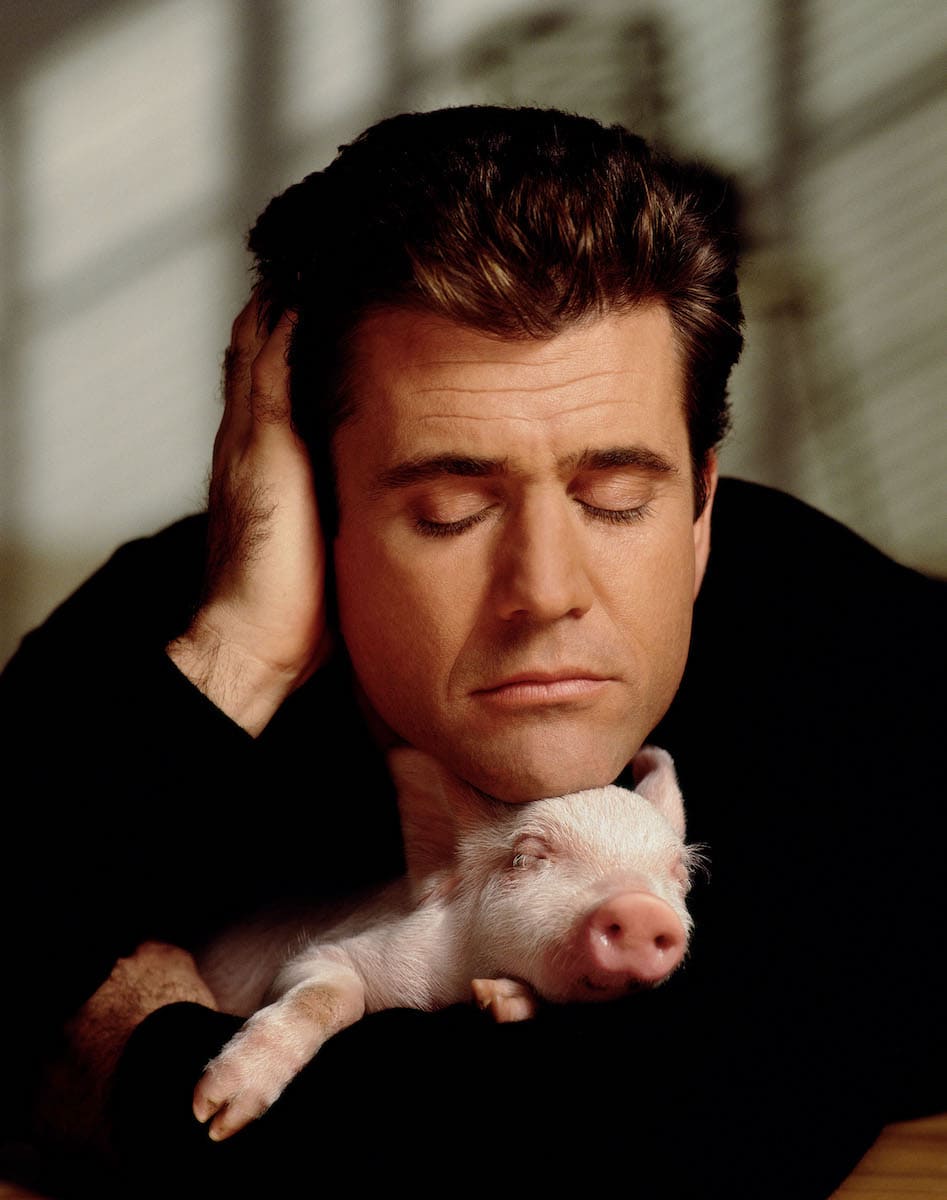

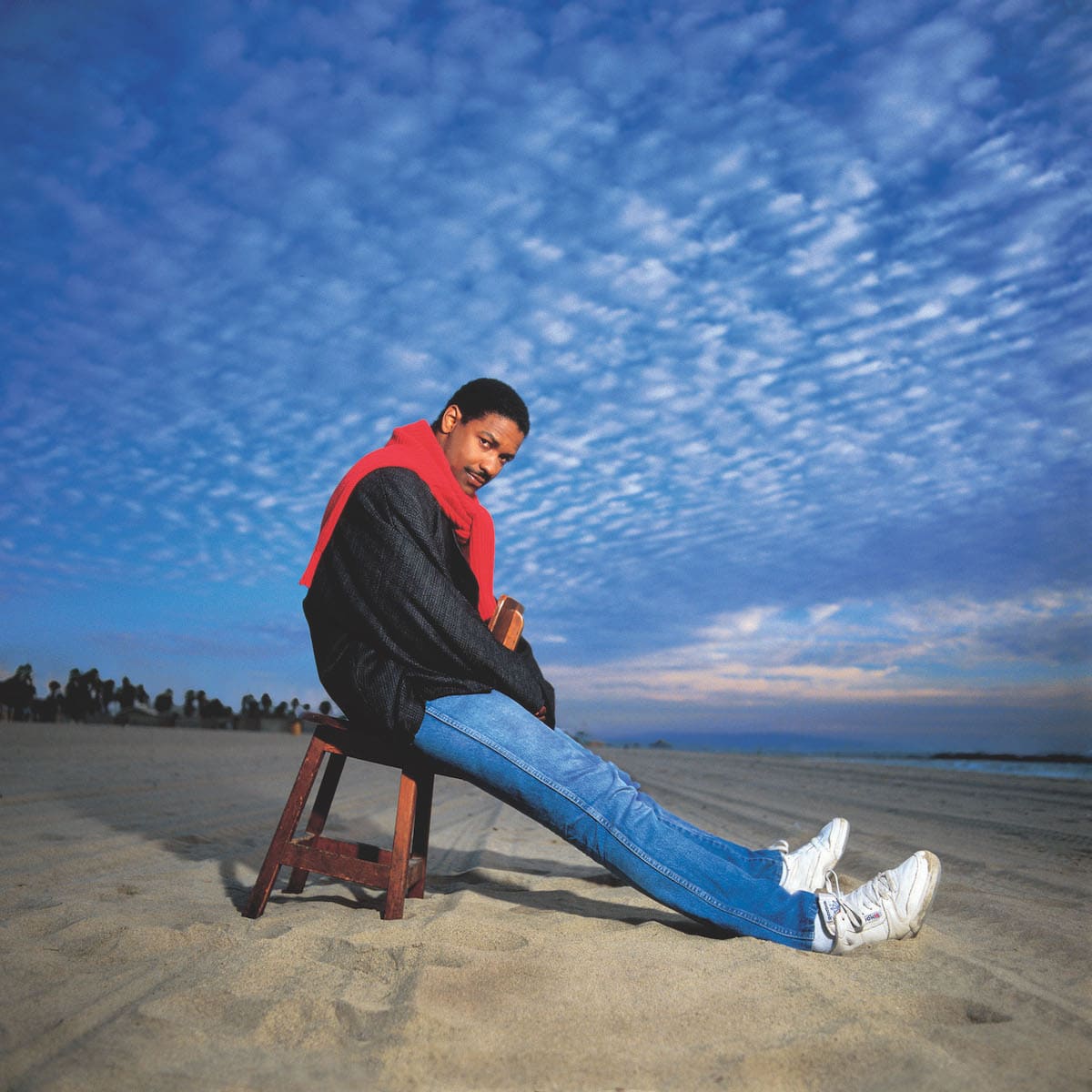

Timothy White captured this transformation in his portraits: from the poses of a generation that needs only a gesture to tell a whole story (Newman’s heedless whistling, the amused dangling of MacLaine’s legs, both immortalised by White in some of his most iconic shots) to the photos accompanying this article in which the actor’s body is the centre of a micro-set, highlighting the symbolic dimension of the character. What emerges from the shots is not the person but the image of a star who often stands out—with due irony (the irreprehensible Gibson needs a pig to make himself likeable)—against a backdrop that tickles our imaginations. How can we forget Ford’s elegance as he casually leaned on a helicopter almost in flight? Or the polished charm of Willis wrapped in the dark theatre backdrop, in which he can either stand or disappear? There is irony in showing Bill Murray crushed by the fate that made him famous as the ‘man next door’, or in abandoning the valiant Denzel Washington on the beach—a party happening in the background—as he offers himself to the camera with a disarming smile, isolated outside the chorus of a system still far from the contemporary criteria of inclusion.

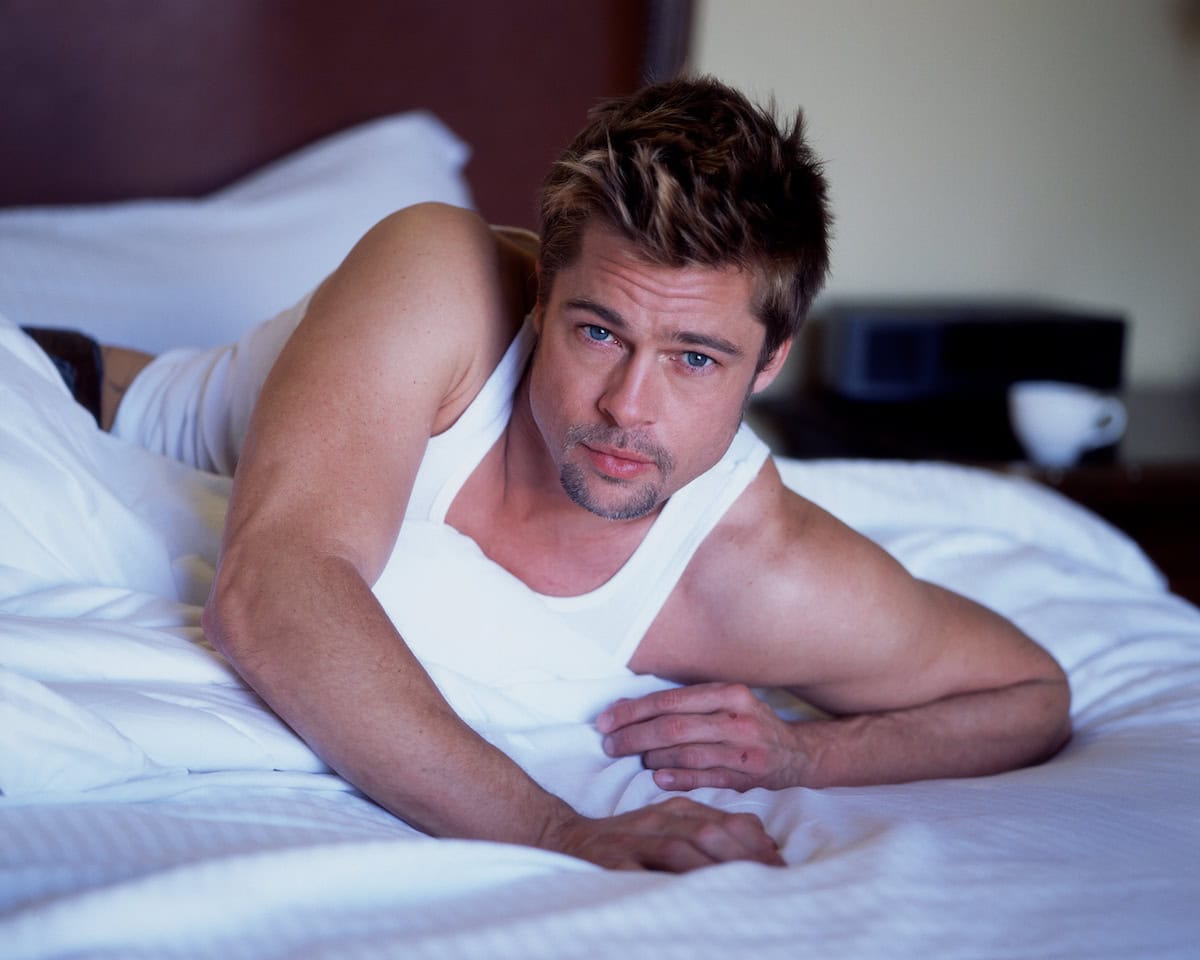

Another generation, however, is all ready to take their place, in which White meets Jim Carrey, Brad Pitt, Johnny Depp, Kate Hudson, Drew Barrymore, River Phoenix, Angelina Jolie, to name but a few. A new style, which increasingly mingles with the world of fashion, plays at anarchy and tries to bring something daring into the equation, flirting with a danger from which not everyone will emerge unscathed. And while the statuesque Pitt (still in search of the light-hearted spirit that defines him today) tries on poses that belonged to Ford and Washington before him, only to end up finding liberation between the sumptuous sheets of a bed, Carrey arrives at the decisive shot, playing with the frame of the painting that has always trapped his subversive and fragile genius, as in years gone by, staging a dissolution of the ego to be reckoned with.

Tea Paci: I would like to start from the very beginning. You initially studied Landscape Architecture. Where did your passion for photography come from?

Timothy White: Oh, it goes back way before that! Growing up, there was a box of family snapshots, filled with all these little black-and-white images, all different shapes because of the different format cameras. They were printed so they had decal edges and that made them stand out for me. Even the composition was odd; it was family members, people around the house, clothing from another period—mainly the 30s or the 40s—or older automobiles, there was this sense of history to them. They had a haphazard sort of composition that later became an aesthetic in fine art photography, the so-called snapshot aesthetic. I loved them as a little boy. As I got older, I got really into movies: I used to sit up late into the night and watch all these old movies, all from those same decades, and I felt I belonged to that time in some way. My parents always talked about growing up during the Great Depression and World War II, so all the history from that period struck me, especially visually. The movies were a way of confirming this aesthetic that I developed. Film noir was such an important thing; the way things were more dramatic—you were very aware of the lighting in those movies—and the mixture of that history, the sense of capturing a piece of it through people and the cinematic lighting stuck with me. I’m the youngest in my family, my sisters were teenagers when the British invaded with Rock and Roll. By the time I was a teenager, let’s say around 14 or 15, I was very immersed in the music and culture of that time, which was youth-oriented and all about sex, drugs and music. I wasn’t going to be a lawyer, for sure! I wasn’t going into the family business because there wasn’t one, so I was always looking for some alternative approach. Photography was very present on album covers and the music scene at the time, and that clicked with me. During the hippie era, everything was very much “save the earth” kind of thing. So many years ago and we still haven’t really done anything about it. That’s what got me into landscape architecture but once I got to school, I realised that there was a lot of science and math involved and it wasn’t me.

TP: It seems like photography was a way to connect you with what surrounded you back then. You mentioned the cinematic root of your love for images and the presence of movies in your life. When you work with actors, are you inspired by the characters they play? Do you feel it is important to play with the cinematic imagery they embodied? Or do you try to create a more immediate connection while shooting?

TW: I’ve always separated the artist from the art. There was something else in the way I was brought up. I was very independent and I had confidence in my ability to interact and engage with people, perhaps it was a little self-involved in some way, but I relied heavily on my ability to connect to people. The truth is that when I’m on set or meeting an actor, I’m so enamoured with their craft and who they are as people that I don’t want to talk about their work. I want to connect with them as human beings.

TP: Your work is extremely prolific. You have covered over four decades and captured some of the biggest celebrities of all time. How do you think the star system has changed over the years?

TW: Oh, it has definitely changed. As you pointed out, I have photographed some of the legends from the period that came before me. I caught the end of it in a way. I was lucky enough to shoot people like Audrey Hepburn and Robert Mitchum. That pushed me to find a style that wasn’t strictly reminiscent of that period, yet respectful of it, and modernise it technically and visually. Hollywood was vastly different compared to now. I came in on the tail end of the studio system when actors had a certain status as an artist and the whole system was just hugely different. Just as I got into Hollywood, the stars and publicists took over and all of a sudden, they were the ones calling the shots, from which photographer to use to the picture for the cover of magazines. That evolves into where we are now, with social media, where stars are totally in control of their image. I was an image maker; I was hired to create an image of that person. Something I often talk about is how photography isn’t truth. Photography is an illusion, my own illusion that I create.

TP: I think we’re obsessed with authenticity today. Even on social media, where you’re in control of your own narrative, there’s always a level of fiction to it. You mentioned Audrey Hepburn before and you’ve shot some of the biggest female celebrities of our time. As an often controversial matter, would you say you have a specific way of looking at female representation? Is it something that resonated within your work?

TW: You mean in terms of gender?

TP: Yeah, I’m curious about the female, but even about more widely gender-related representation. Were you involved to some degree in the cultural discourse around it?

TW: In my mind, it’s really about my own connection with human beings, whoever they are. When I photograph Raquel Welch, she’s a sex symbol and so I want to show her in a way that exemplifies who she is or what her image is about, and still make it my own. When I’m working with Audrey Hepburn, she’s a different person: soft and gentle and wonderfully talented. And it wasn’t about sex in the same way as Welch. Between those two is Sophia Loren, who had qualities from both sides. She has all this depth and sensitivity, but she’s also very sexy. I’m aware of the image and I’m aware of the essence of the person I’m shooting, but equally, I just try to relate to people and let the shoot evolve.

TP: Can you share some memories of shooting with Sophia Loren?

TW: Oh, Sophia Loren! You asked me about the difference between Hollywood and the rest of the star system. Well, I photographed Julia Roberts and she came in with her bossy publicist who was in charge of everything, and then you have Sophia Loren, who shows up by herself at 8 a.m. I react very gently because she’s larger than life and someone who I deeply revere and love. I turned to her with my hands clasped very sheepishly and said: “How long do I have you for so I have a sense of what I can do with my photo shoot?” and she replied: “I don’t know, 4 o clock?” I got all that time with her! That’s the difference between that level of Hollywood and the current star system. She was amazing and so receptive. I took her to the beach wearing a gown and running into the water, I got her dancing, got her in bed holding a pillow and wearing jewellery, or wearing this Armani dress that she playfully whipped open to show me her legs. As a young guy at the time, to be able to direct these big stars, people who I put on a pedestal and wanted to emulate, was amazing, and she was just wonderfully collaborative.

TP: Speaking of collaboration, you are also a partner in an art gallery—the Morrison Hotel Gallery in Los Angeles. Can you tell us about that?

TW: After studying Landscape Architecture, I went to the Rhode Island School of Design. For me, it’s always been about Art itself and the history of Photography. I’ve always been inspired by other photographers, studying their styles and their work. I have a huge collection of Art books that I’ve been collecting for 50 years now. We opened up the gallery 22 years ago. It started with only a couple of photographers. I was one of them and then became a partner later on. We represent 125 photographers, most within a certain genre, mainly music and entertainment photography, but I still recognise individual approaches and get inspired and excited by that.

TP: Is there anything you want to add about your practice as a photographer?

TW: I am a very technical photographer. In my world, I had to show up and know what I was doing in any situation because I was working with these high-level people. But I always say, if I prepare too much and have too many expectations, it’ll get screwed up. My career is really about my interaction with people and trying to create an experience that I can involve them in. I build out a window to let the magic happen. I’m very precise: I know composition and light, but I have no idea of the result I’m going to get with the person. I just play it by ear and have the confidence that I will get something from that work.

TP: You have had such a rich life, full of incredible encounters. Will photography remain your only medium or have you ever thought it might be time to start writing about all this?

TW: I’m actually writing my memoir and it’s an exciting process. Writing is a whole other creative outlet from before and I’m now able to look back on my life with different eyes. In terms of structure, it’s not just stories of my photoshoots. It’s really about who I was, how I grew up and how my background formed my photography—throughout my career up to what I’ve learned where I am now.

TP: That’s wonderful. Thank you for this conversation.