I met Greek photographer Antonis Theodoridis while installing his new exhibition at the 2023 Eleusis European Capital of Culture. Fresh from a compelling 6-week residency in Osaka, where he explored the convergences and divergences of Greek and Japanese cultures, Theodoridis brings forth a distinctive artistic vision. His practice integrates diverse photographic strategies and installations, skillfully examining the tensions between fluidity and stasis, personal and historical memory, the imperfect and the pristine. Rooted in astute observations of his surroundings, Theodoridis’s process propels an ongoing investigation of the photographic medium. This evolution not only shapes his work but also challenges the ways we perceive and engage with pictures.

Nicolas Vamvouklis: The residency you joined was part of the “Mystery 8 European Eyes on Japan” program, focusing on the relationship between these two cultures. What were your expectations before this journey?

Antonis Theodoridis: My idea was to synchronize my journey with the arrival of the Japanese cherry blossom and the celebrations of Sakura, which is deeply rooted in culture and life in Japan. I had numerous mental images and scattered thoughts on what to expect. Familiar with Japanese culture, which I believe interweaves with our ‘Western’ culture in countless ways—be it in beauty, fashion, anime, arts, spirituality, or intellectualism—I have always been curious about it. I arrived in Osaka a few days before the full bloom of cherry blossoms, following a few rainy nights in a small hotel room in Tokyo. It overlooked a chaotically colorful array of LED skyscraper facades by the Shibuya Crossing, and I spent many hours lost in the city. In Osaka, life moved slowly – yet everything still felt new. By that point, most of my expectations became irrelevant, and I just went with the flow of everyday routines.

NV: Besides the Sakura festivities, your new exhibition is influenced by the myth of the abduction of Persephone. Can you share how these elements shaped your vision during your residency?

ΑΤ: I was tasked with working on a project that would conceptually bridge two seemingly irrelevant places, Osaka and Elefsina, using Persephone’s myth as a thread. The proposal was to take a Greek myth to a faraway place to unpack it, transform it, or, in a way, visually “translate it to Japanese.” Most of us are familiar with this myth back home, but some underlying dynamics and interpretations are still in flux and often evade us.

I began by shooting portraits of both men and women—strangers I encountered at the park near Osaka Castle. Eventually, I decided to focus on young men. It felt more right at the moment and had an introspective quality. This helped me let go of the idea of building a gender-rigid narrative and imagine a story where Persephone could be anyone, how liberating that could be, and what new interpretations I could extract.

NV: You attempted to create a counter-myth that transcends traditional ideas of beauty. What did you find challenging to reconcile between the Greek myth and the Japanese context?

AT: What made this challenging was that my understanding of the Japanese context was minimal initially. Japanese culture and modern society are complex; it requires personal experience to detect its subtleties, symbolisms, and pathologies. We also tend to exotify the East in a way that can be very distorting.

On the contrary, Greek myths are rooted in our life story and education back home and seemingly belong to our sphere of “understanding.” These stories survived thousands of years and seem carved in stone, but in reality, they are changing constantly and unpredictably. I would be reluctant to look for true meaning in this myth; many moving parts and intricate emotions exist. This allowed me to embrace a state of not-knowing or, in essence, un-knowing, feeling lost and curious. I focused on my emotions, seeking a sensitivity within myself to reconcile all these loose ends.

NV: The portraits of young Japanese men in this series are striking, and I particularly like their vibrant colors. Could you elaborate on their significance in your exploration of love and transition?

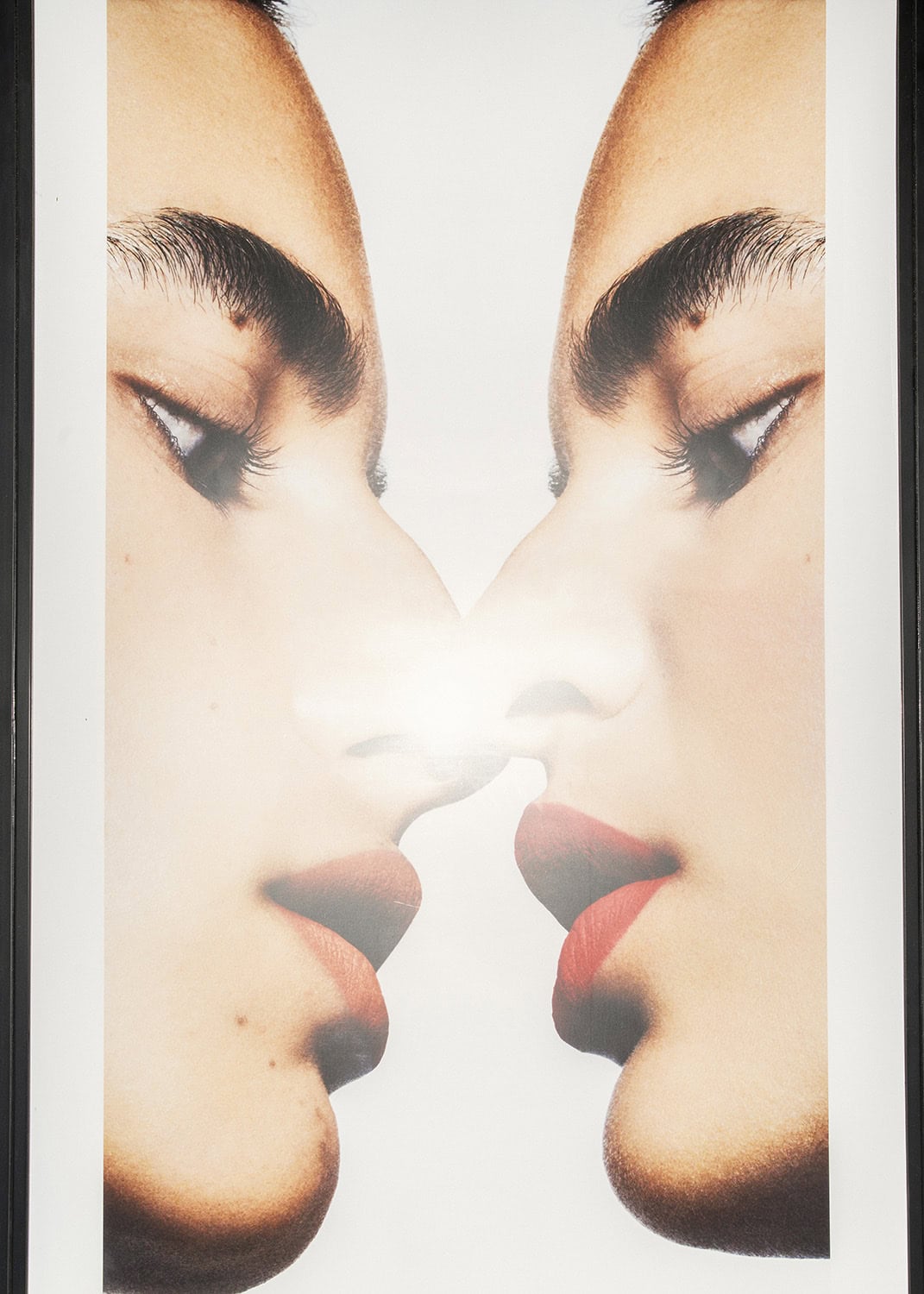

AT: On one hand, they were personal encounters, quite intimate or joyful, that helped me tap into personal feelings and open up. On the other hand, I chose to photograph this portrait series in a somewhat formal fashion instead of casually shooting moments. In a way, I wanted them stripped of their surroundings against a plain background by the river of Castle Park in Osaka. I wanted them to feel gently exposed in the moment, and I felt the same way, too. There was a sense of togetherness in a fleeting moment, strolling and sitting on a ‘carpet’ of green grass and fallen petals. There was a kind of love in the air – a fleeting kind of love. I hope that is reflected in the pictures.

NV: Your daily photographic process evolved into a rite of transition, seeking to welcome spring with a new understanding. Can you delve into how photographing locals, especially young couples, became a symbolic part of this shift for you?

AT: Young couples embodied this spectrum of personal emotions I tapped into. The idea of togetherness, romance, and love that is so masterfully intertwined in the myth of Persephone, along with a sort of violence that comes from the fleeing nature of spring and time itself, became a metaphor for how fragile these moments are, how fragile we can be ourselves. My practice did indeed feel like a daily rite of transition. No two days were the same. The trees turned greener, the weather changed, and the mood switched. The arrow of time felt so present the whole time.

NV: What do you hope visitors will take away from your show in Elefsina?

AT: Visitors can unpack a fresh and true sensitivity. I hope they will enjoy the work and think that while faraway places can be exciting too, what we long for, and search for is often just a breath away.

The exhibition “The Return of Spring (and Other Rites of Transition)” by Antonis Theodoridis is on view at the Leonidas Kanellopoulos Cultural Center in Elefsina, Greece, from December 14, 2023, to January 21, 2024.