The paradox of design is that despite it being very much a discipline that moves within the contemporary, its ultimate goal, more often than not, is to achieve the status of timeless icon and therefore outlive its own era. If this happens, these objects survive the passing of the years, evading aesthetic and cultural fluctuations to become mythological representations of the search for absolute, eternal beauty. Flos is one of the companies that have most contributed, over the years, to expanding our panorama of icons, producing mythical pieces that have outlived their creators and their own time. However, the big question when it comes to spontaneous—as opposed to imposed and dogmatic—iconography is whether or not it’s possible to predict success. This question underpins the tension inherent to every nascent project, both curse and stimulus for the designer at the beginning of the design process.

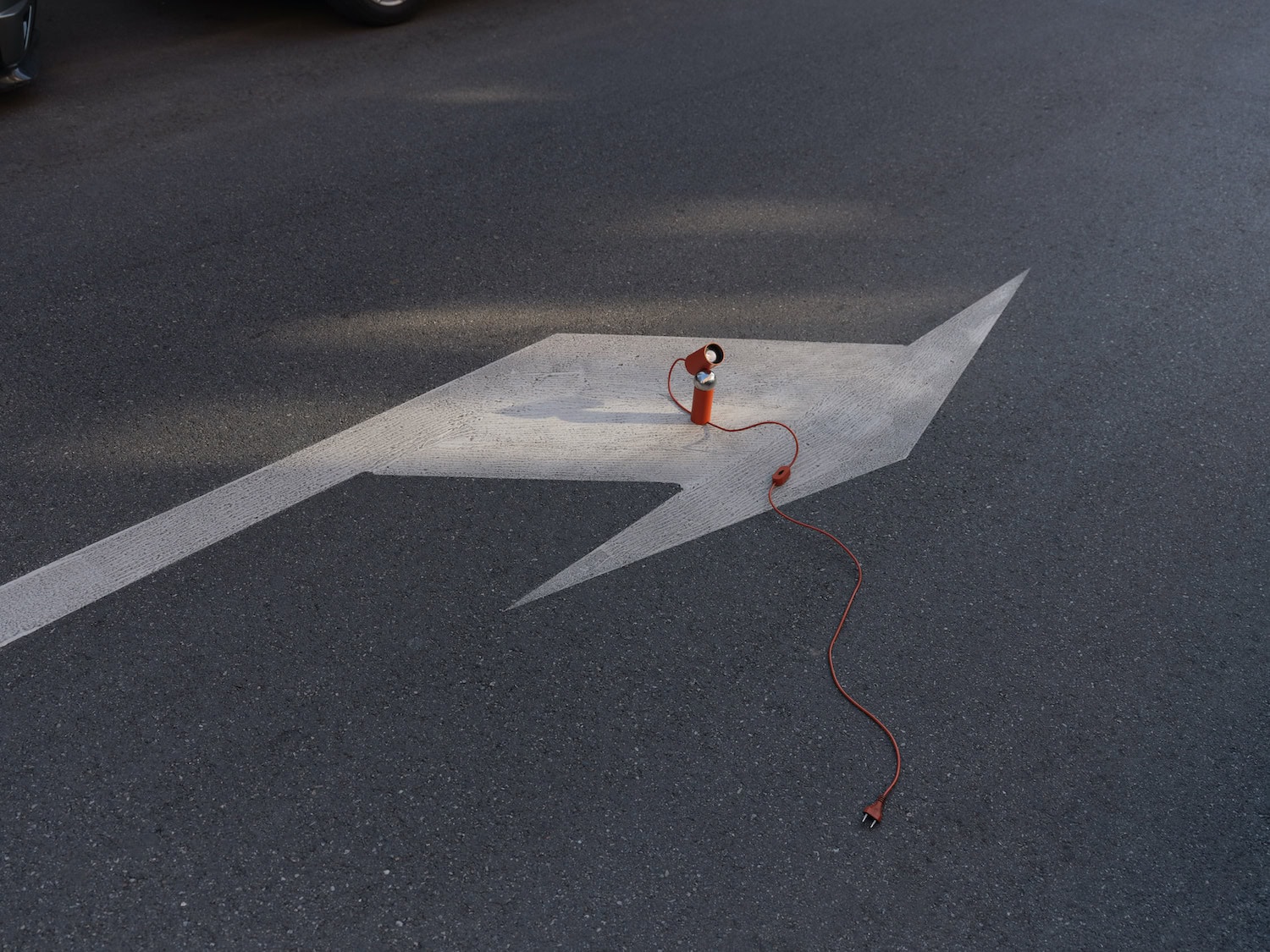

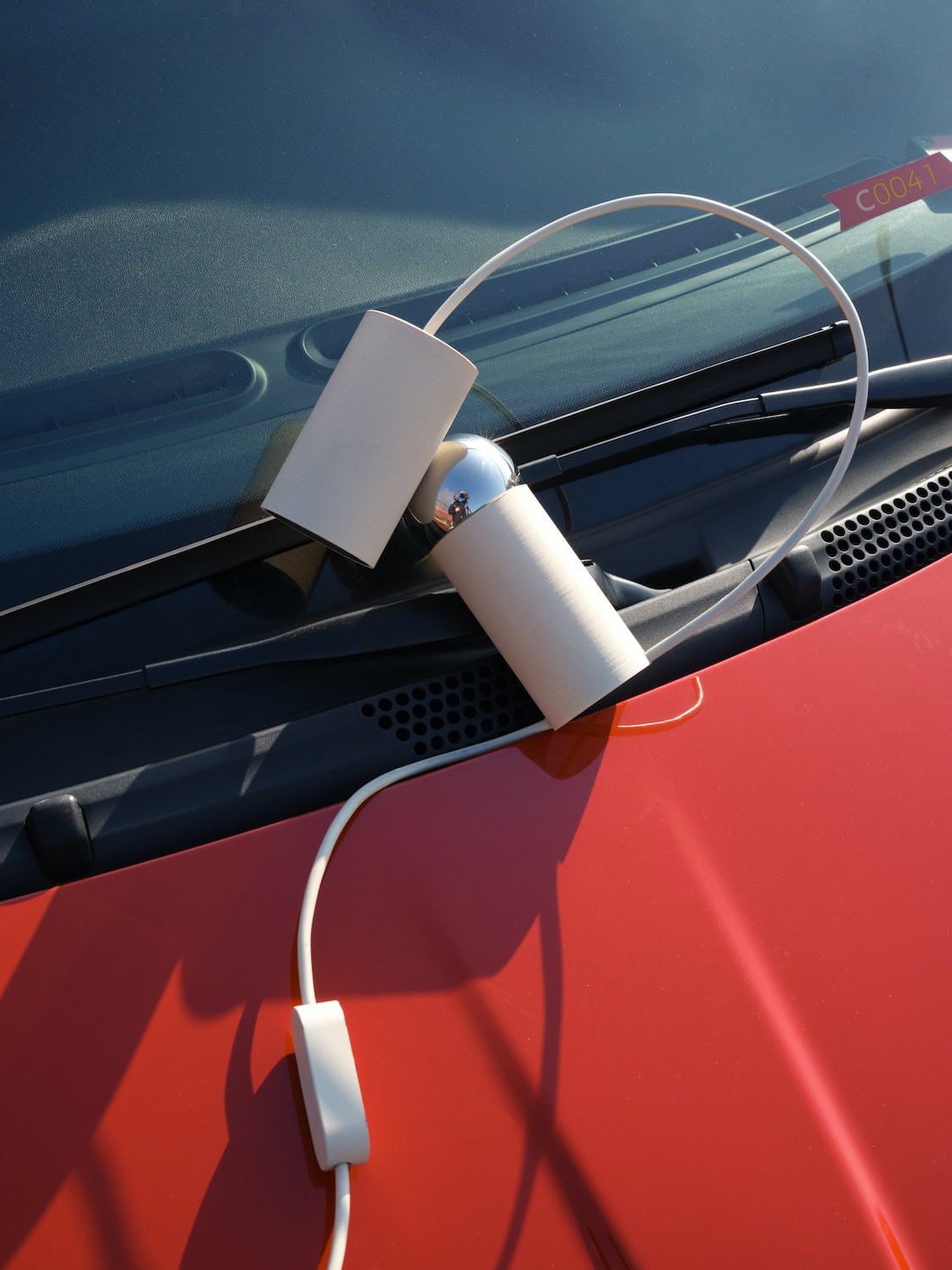

It was 2019 when Flos and Philippe Malouin started down this road together and the design object took shape after almost four years of work. Two cylinders and a sphere, technical and formal child’s play by all appearances, but you need to be able to handle extreme complexity in both areas in order to hide the functioning of the lamp and achieve purity. Bilboquet is a perfect representation of the two souls that brought it into this world. On the one hand, Flos, which has a wealth of technical and technological knowledge on hand to overcome obstacles, leaving freedom of expression and movement to the designers; on the other, a designer like Philippe Malouin, able to handle shapes and volumes with the ease of somebody who has never pursued a style but has developed one over the years.

Some things just happen at the right time and whether you see magical, random, natural, or mystical factors at play, there is no denying that they do happen. This appears, quite simply, to have been the right moment for them to come together in search of the kind of beauty that only some can create but that we all need.

Tommaso Caldera: Hi Philippe and thanks for being here. It’s a real pleasure to talk to you about your collaboration with Flos. I would like to start from the very beginning, could you tell me how it all started with Flos?

Philippe Malouin: Well, I was very lucky to be considered a Flos candidate. Paolo and Fabio, who are the art directors of Flos and also have a practice called Calvi Brambilla, sent me an email at the beginning of the pandemic. It’s something we’ve been working on for a while. I wasn’t expecting it and I was very excited. We started the ball rolling with ideas for a possible collaboration and that’s how it started.

TC: Could you describe the lamp you have designed?

PM: It’s a small, rotating table lamp that uses a very simple magnetic joint. I’d had this joint at the studio for a really long time and that was the starting point for the lamp. Something I love about Flos products, especially Achille Castiglioni designs, is this sense of involvement with the user. You can adjust the light to where you need it. I have two Parentesi lamps at home and I am constantly adjusting them, depending on where I want the light. You know, sometimes I want to bounce light off the white ceiling so that it diffuses a certain way and sometimes I want to highlight certain things. I think light is really dynamic. It’s not a static thing because your needs throughout the day change and you can adapt by aiming the light at the ceiling or aiming it at a table and so on. The intensity and the light quality change so that’s something that I was really interested in exploring. And Achille Castiglioni’s work was an extreme source of inspiration.

TC: How did you decide on a table lamp? Was that something you discussed with the brand and with Fabio and Paolo or did you bring your idea to them?

PM: There was definitely an initial brief for a smaller product that was easily identifiable in terms of scale, colour, texture, and the type of light it was giving off. That was one of the starting points. It was also meant to be a more democratic product. I’ve been an industrial designer for 14 years but when you work with someone like Flos on a mass, global scale, the price, and the target demographic are important, so that’s something that we definitely considered.

TC: And did you come up against any technical issues during the design process?

PM: Yes, the technical development was very much a back-and- forth between me and the Flos Product Development team. We wanted to make this magnetic product that you can aim where you like. It’s a very simple idea and I came up with the proportions and schematics for the assembly and components. Calculating the amount of magnetism that you need for the product to be usable is not simple, however, and that’s where the very intelligent people from Flos come into play. There was a lot of moving forward and evaluating, and every time we thought we had one issue cornered, another issue would crop up and it was very much a start-and-stop process for a while. I have to say that most of the problem-solving was done by Andrea and Francesco from Flos Product Development.

TC: You mentioned that your collaboration with Flos started before the pandemic. Do you think that the pandemic had an impact on this relationship and the design process in general?

PM: There was definitely a lot less physical presence. A lot of this development was done virtually, which is something that we used to do but not with such frequency. You’d be there in person for most product reviews so that was a massive change. We obviously had many prototypes of many different lamps before deciding on this specific one and things would get shipped back and forth and re-evaluated. The process was less direct but also much more documented in a way because everything was clearly written down and there was this really fantastic evolution. Working virtually has evolved and I think it has had an impact on how we work with most brands and perhaps especially how we work with brands in Japan or America. I guess we’re more comfortable doing this than we were before. And at the beginning of the pandemic, some of us thought it wasn’t going to work but I think we just got used to it.

TC: I really love the decision to oversize the joint element instead of hiding it. Designers usually prefer to hide those elements but you’ve done the opposite and that’s the core of the project. Was designing and developing the joint a technical challenge?

PM: Yes, on many different levels. The ball is a stainless steel ball and the amount of carbon in the ball needed to be just right so that the ball doesn’t oxidise. So the ball itself was a big part of our research. The reason for going in this direction was that I’ve done a lot of work in the past using rotating pieces and ball bearings. I’ve done giant works in nylon, for example, that had two giant moving plates and the only thing that we used were balls. It’s very much a continuation of the work that I was doing five years ago with these balls as the mechanical element and I didn’t hide them even though I could have. It’s utilising function as a means for the user to immediately understand what the product does because when you try to hide something, I think form and function drift a little. We wanted the user to immediately understand that the lamp could be rotated because of the ball joint.

TC: This object has a powerful interactive aspect. You can move the light diffuser freely around the joint and you can remove it and replace it. And the sound when you replace the upper part is really cool and sharp. Did you have this in mind from the beginning or did it develop as you were working on samples?

PM: It came up when we were working on the sample. We tried something different to our original idea and the way everything came together was very satisfying. At that point, we also considered packaging, how would the product be shipped to you? Paolo, Fabio, Francesco, Andrea, and I all decided we wanted people to have an experience when they unpacked the product and put it together, so that interaction you mentioned was devised to create a positive and wondrous user experience, like so many Flos products. I keep coming back to the Parentesi lamp…

TC: I remember the original Parentesi packaging, it was really cool. It was a transparent thermoformed plastic case that didn’t hide the product.

PM: Yeah, and most importantly you understood that the wire needed to be under tension and there was a weight that needed to be there for the product to work. There’s this unveiling and putting together and that is part of the experience as well. Once again, that’s something that we all jointly considered.

TC: I’d like to talk about lighting objects in general because they are both everyday and magical at the same time. They need to function within our spaces both when on and off. As a designer, how do you manage the dual nature of this object?

PM: I think simpler compositions are usually the winners, that’s my personal preference anyway, and so the design is incredibly simple. It’s two identical cylinders and one ball. And in a way, it’s a little bit like a palindrome, you can move it this way or that way and it’s always the same thing. There’s a sculptural quality to the light object when it’s not being used. And I think that’s very difficult to achieve, but it’s definitely something that I’ve been trying to work on. It’s about finding the right balance between sculpture and function. We’re very lucky here because this light object is both sculptural and highly technical and functional in terms of orientating the light so we just needed to find the right balance and I believe we achieved that.

TC: I’d like to talk a bit about your personal language and your personal approach to design. I really love your ability to combine simple volumes and produce something that is minimal yet fresh and powerful. I would define it as a sort of fresh minimalism, far removed from the cold and boring minimalism of the 1990s and closer to Ettore Sottsass or Memphis. Do you agree with this definition?

PM: I’ll take it! I definitely think that it’s up to talented people like you to recognise what something is and isn’t. I rarely think about what my style is or how it should be perceived. There are usually simple shapes and simple volumes and they always have to have an aspect of discovery or fun about them. I don’t mean like a joke, that’s terrible design, well, it’s different design, it’s not what I do. It needs to be extremely simple in terms of design language and the function or daily usage needs to inspire emotion. As far as shapes go, I generally utilise the materials readily available in the studio, cutting them and putting them together, mostly by hand at first. That’s something that you can see in my work. My gallery work is only 5% of my practice and my mass-produced work is the other 95%, but they really inform each other. I very quickly try to mock things up and maybe this way of working has an effect on how I design things. But all the shapes usually come back to function and they’re very much speaking to one another.

TC: Was it easy to combine your personal approach and workflow with a company with such strong heritage?

PM: It’s terrifying if you’re an industrial designer. I come from a small town in Quebec, I come from nowhere, and I got really lucky because I was able to come and study in Europe and I got to stay in Europe. The point I’m trying to make is that when a company like Flos calls, it’s the most exciting thing to happen to you, but it’s also terrifying. Because you might not have something that they like or you might not get it right, there’s a lot of pressure that comes with that initial contact. And as I said, you take two steps forward and one step back because you think you’ve solved one problem and then another problem arises, even with something that looks so simple. There is a certain amount of stress involved with wanting to bring the way I work to a company like Flos, but it worked out in the end. I think it was always meant to be.

TC: When it comes to contemporary design, do you think it’s at all possible to define what a contemporary language or contemporary approach is?

PM: There are so many references to what design is about that I don’t think contemporary is applicable. I think there’s room for everybody to have their interpretation of what design is although I know some people will think there’s a right way and a wrong way of doing design. I have had discussions in the past about how everyone’s interpretation of design is their own and how your social context can change everything and there’s no such thing as the right way or wrong way to design something. I think it’s kind of tyrannical to be told what’s right and wrong. What contemporary design means to me is infinite interpretations and, most importantly, where people come from, what tastes means to them, and what influences their decisions. Mine happens to be very simple because it’s what I prefer aesthetically and my approach is very much about making and making errors and building upon that. Other designers are more about referencing things that existed before and reinterpreting them. I went to Design Academy Eindhoven and the reason I went there was Droog Design, because it had this extreme DIY approach to making things work in a design context. That’s what influenced me originally but then obviously, as I grew older, design masters such as Castiglioni, Eames, Jasper Morrison began to influence me. Anyway, to answer your question, I don’t believe there’s such a thing as a contemporary design. Everyone makes design what it is.

TC: You’re part of a new wave of young designers. This is the first, maybe the second, generation after the masters. What do you think are the main differences between their generation and approach and yours today?

PM: At the time, I believe there was definitely an overwhelming sense of domination from the Italian Masters. They were very much hand in hand with the industrialists that were dotted all around Italy so they had the capacity to manufacture on a broad scale and the capacity to design a very strong aesthetic language. Then I think, as years went on, you had the generation of Jasper Morrison, Konstantin Grcic, the Bouroullec brothers, and Barber Osgerby—all of whom have actually designed for Flos—which was much more international. And I guess what influenced that openness to working with designers that weren’t in the country where these industrial products were being produced had to do with the fact that not everything was centralised. So when things weren’t centralised, there was new capacity to work with all designers from all over and I believe my generation is perhaps a continuation of that. I’m London-based, like a lot of other designers, and maybe there is a geographical advantage to being able to easily access the Nordic countries, Italy, and France. And I’m very glad to be part of the conversation for designers these days because it’s a huge responsibility to be given an opportunity by Flos.

TC: My last question is about your personal preferences beyond design. I’m really curious about any of your preferences outside the design world.

PM: Definitely art. Art for art’s sake, really. Things that are created in order to create. That’s something that I was talking about earlier: that sense of wonder. It’s about creating an emotion and a feeling and having the capacity to do that is overwhelming in art. It goes without saying that the 1950s and 1960s American minimalists can be a big influence because they created such overwhelming emotion out of so little. Arte Povera in Italy as well. The evolution of doing more with fewer resources and creating such strong art with very little. That is a huge inspiration for what I do.

TC: Thank you and good luck with your collaboration with Flos. See you in Milan!