Meet Bettina Pittaluga, a French-Uruguayan photographer based in Paris, France.

Her career started off as a reporter who studied sociology. Although her career as a photographer was not her initial pathway, her passion and admiration for it started at the young age of 14, when her uncle gave her her first ever camera.

At that age, Pittaluga was living in a small town in the south of France where she would spend all her hours after school learning how to use a film camera and how to develop her own black & white photographs. Evidently, this encouraged her to take pictures all the time, capturing family, friends and anything that sparked an interest within her.

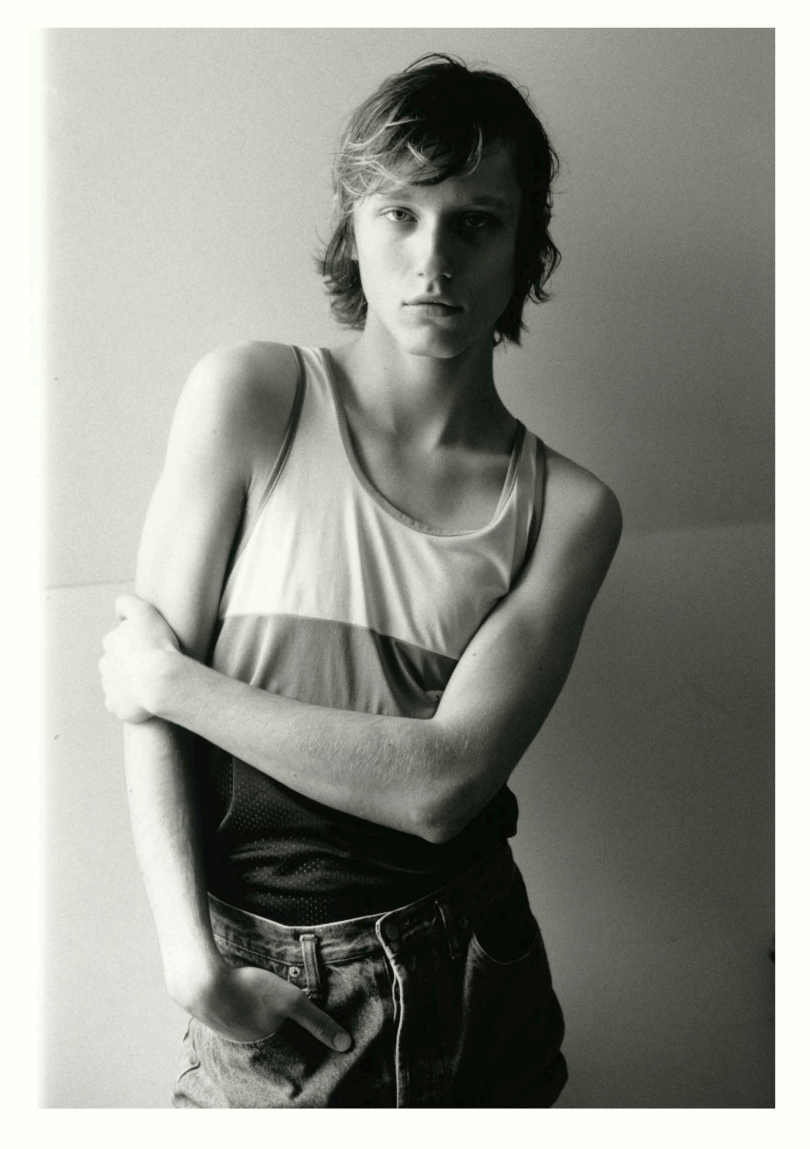

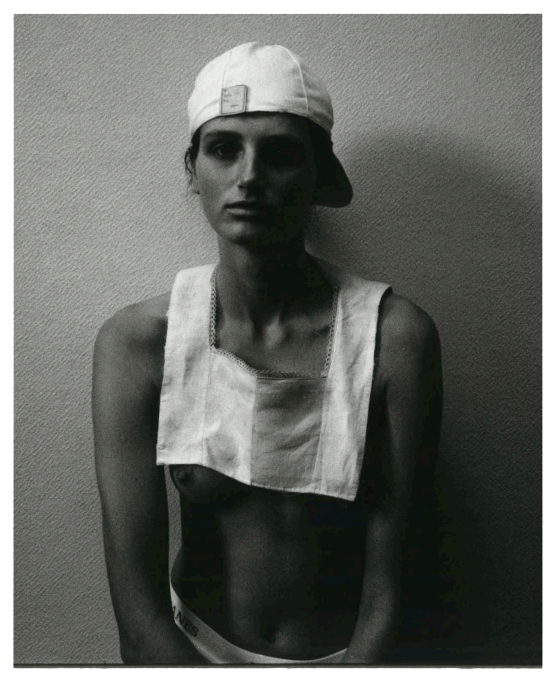

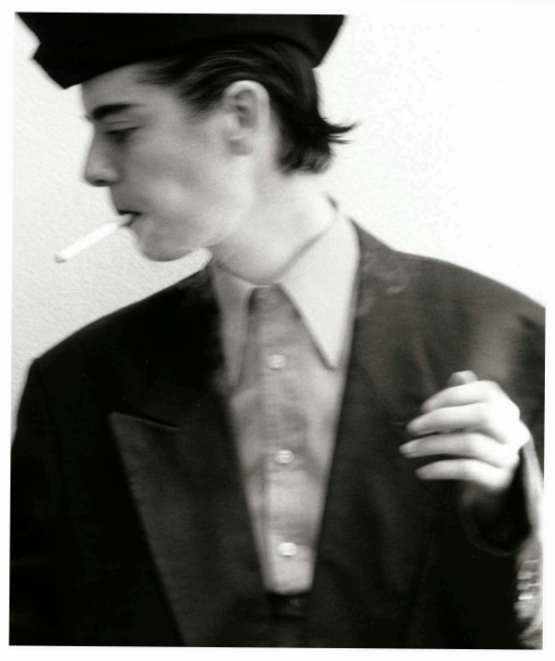

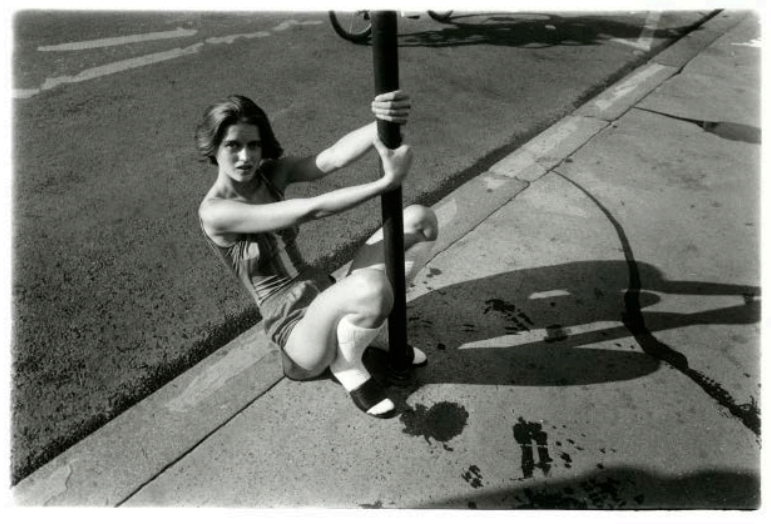

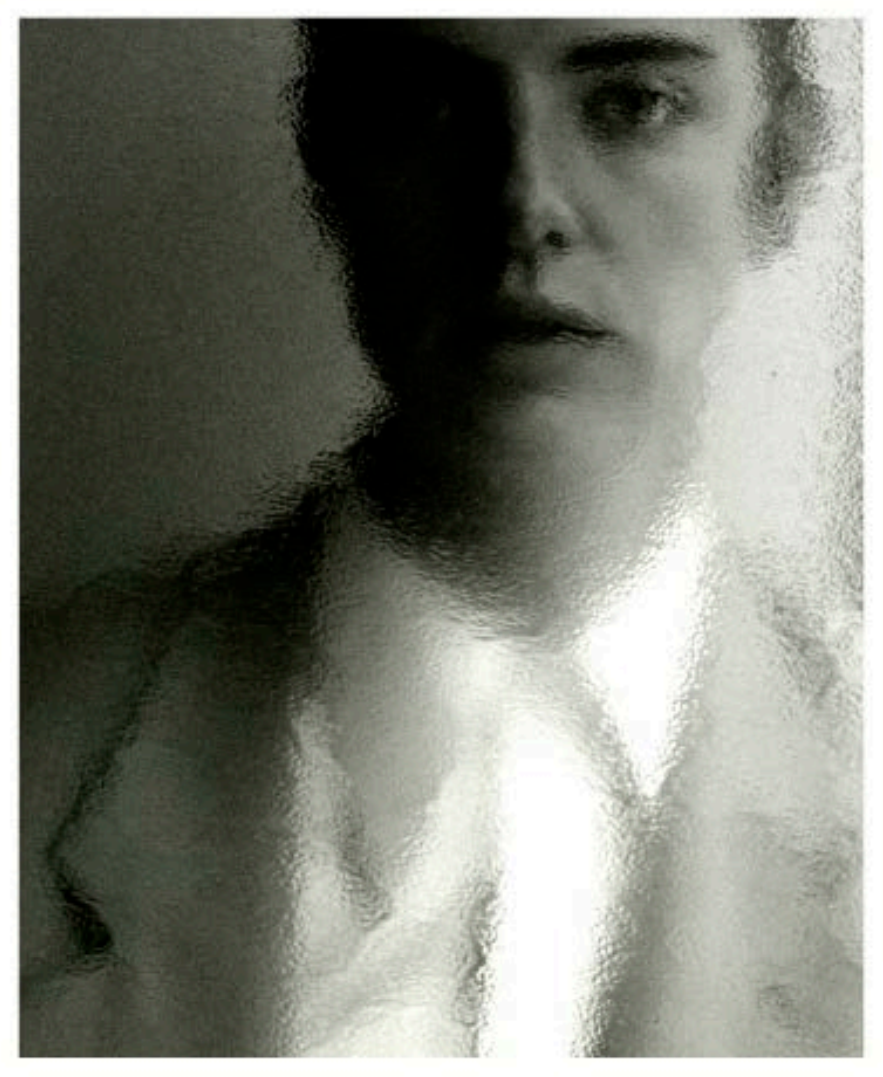

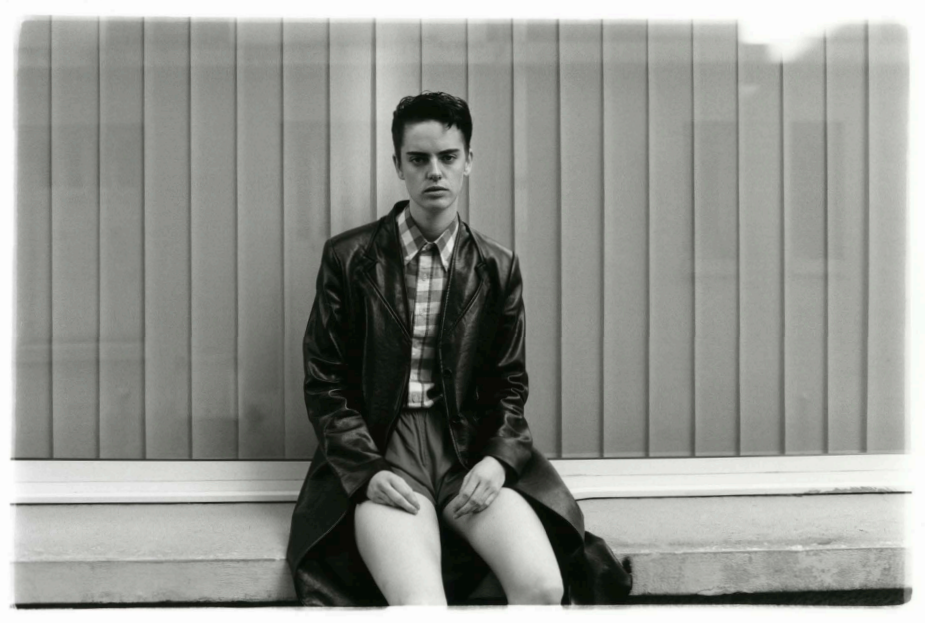

Pittaluga’s body of work consists of a strong sense of intimate and vulnerable moments captured through a delicate lens; documenting marginalized communities and uplifting their voices. Her work has been featured in the likes of PhotoVogue, M Magazine as well as YSL’s Rive Droite fanzine.

Through her photography, Pittaluga prioritizes the fight against the objectification of individuals seen within society’s norms. The morals and values she lives her life by are carried into her work as well; an important factor of her creative process as one is not inextricable from the other.

Nisha Kapitzki: How important is fashion in your visual identity? Do clothes play a role in your storytelling?

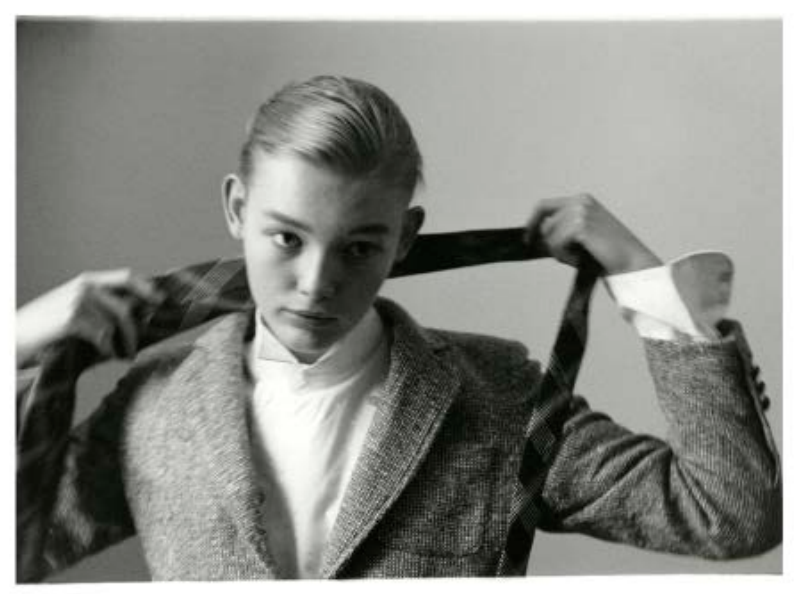

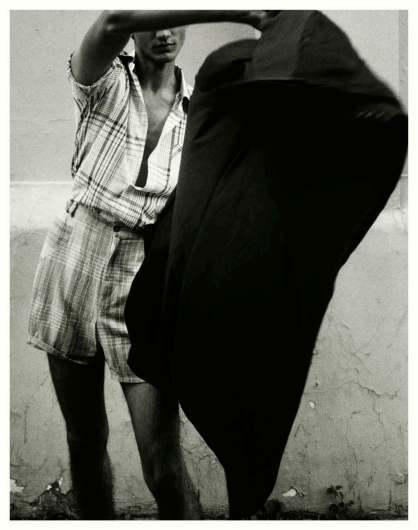

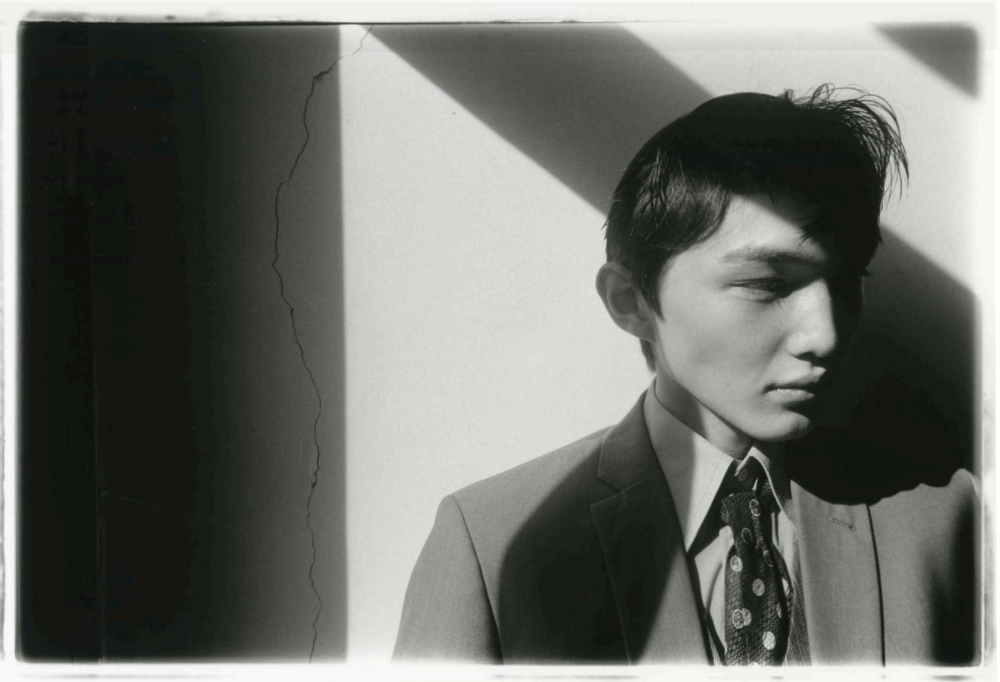

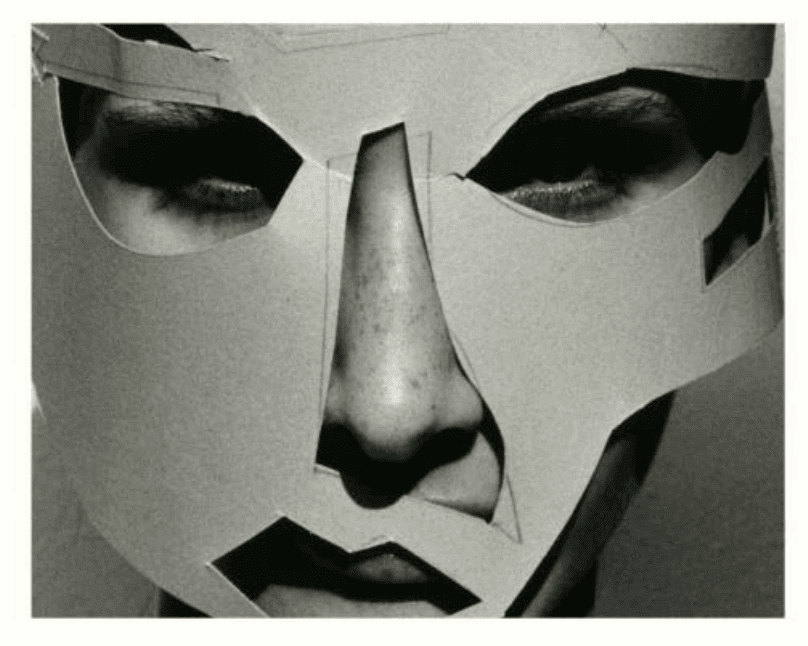

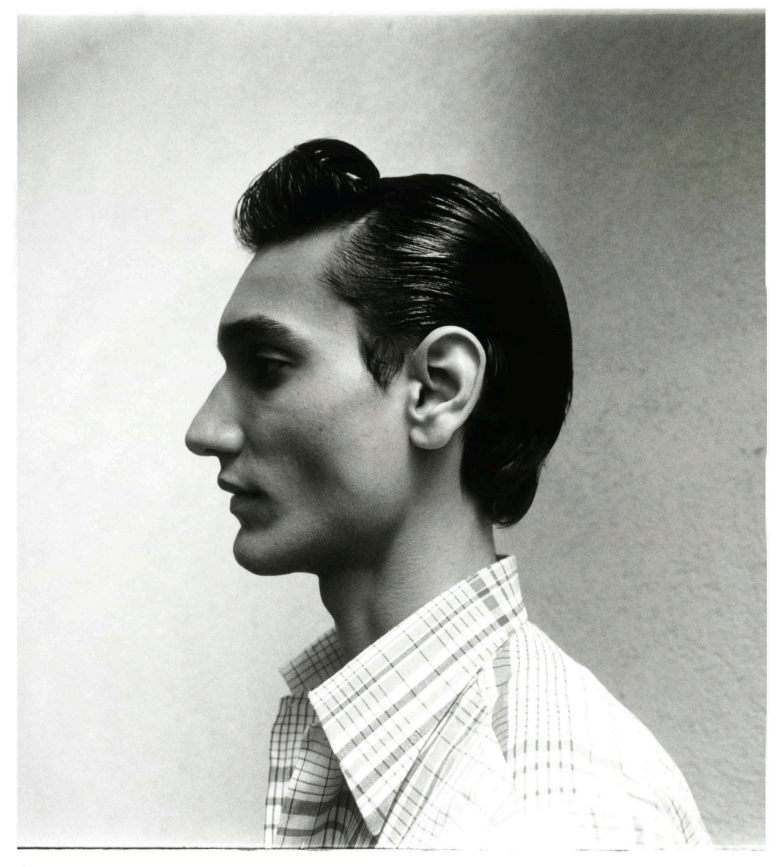

Bettina Pittaluga: Clothing, to me, is a silent extension of identity. They tell stories, sometimes consciously chosen, other times inherited. In my work, I consider them as full-fledged narrative elements. They can reveal, conceal, or even divert attention. What interests me is how they contribute to constructing a visual narrative.

NK: When photographing a subject, particularly in fashion editorials (e.g., your work for M Magazine, Carhartt, etc.), how do you approach clothing as a tool to shape their persona or identity?

BP: I don’t seek to shape a character but rather to reveal facets of the person that may be unsuspected. Clothing then becomes a tool for dialogue, a means to explore zones of comfort or discomfort. It can amplify an emotion, contrast with a posture, or highlight a presence.

NK: Do you think clothing conceals or reveals identity—or both? How do you play with that tension in your photography?

BP: I like to think of clothing as armor. It can protect, camouflage, but also unveil intimate parts of oneself. In my photographs, I enjoy exploring this duality by playing with textures, cuts, and layering. It’s not so much about revealing or hiding, but rather about opening a space where identity can unfold freely.

NK: How involved are you in the styling process when building a character or narrative in your series?

BP: My involvement varies depending on the project, but I like to be present in the styling process to co-construct an aesthetic that makes sense. I often work closely with stylists so that each clothing choice resonates with the story we want to tell. It’s a work of listening and adjustment, where every detail counts.

NK: Do you believe fashion photography can function as a form of archive or anthropological record?

BP: Absolutely. Fashion photography, beyond its aesthetic aspect, captures moments, codes, and attitudes specific to an era. It becomes a visual testimony of the norms, aspirations, and revolts of a society. In this sense, it can be a valuable archive for understanding the cultural and social dynamics of a given time.

NK: If you had to pinpoint the key elements of your work in terms of visual identity, what would they be?

BP: I would say: intimacy, grounding in reality, and emotion. My goal is to capture moments of truth, no matter how fleeting.

NK: Each portrait you capture has a vivid casting that vibrates an essence of tenderness between the lens and the subject. How does the casting process work for you? And how do you accentuate their identity within your photographs?

BP: Casting is a crucial step. It’s something I’ve long built on my own, often through street casting. I look for people with whom a connection can be established, there’s a feeling. Once this connection is established, I strive to create an environment where the subject feels confident, free to express their uniqueness. I guide little, preferring to let gestures, glances, and postures emerge naturally. It’s in this spontaneity that identity reveals itself most sincerely.

NK: In previous interviews, you state that your body of work goes hand in hand with your moral compass and lifestyle that you lead. Do you believe photography has a responsibility in shaping how society sees beauty, race, gender, and identity? How do you navigate that responsibility in your work?

BP: Photography, as a powerful visual medium, undeniably influences social perceptions. It can perpetuate stereotypes or, conversely, deconstruct them. I’m aware of this responsibility and strive, in my way, to offer more inclusive and nuanced representations. This involves choices of subjects, team, themes addressed, and a constant reflection on my position as a photographer.

NK: Your portraits celebrate humanity in small, quiet ways. In an image-saturated world, do you think slowing down and showing softness is a way of pushing back against overstimulating narratives?

BP: Yes, I sincerely believe so. In an era where images are omnipresent, often fast and spectacular, choosing slowness, softness, intimacy, and reflection is a form of resistance. It’s a way to reaffirm the value of humanity, authenticity, and sincere connection.

NK: What have you learned about human presence and emotion through your intimate process with photography and models?

BP: I’ve learned that presence cannot be dictated, it invites itself, often in the interstices, silences, and breaths between shots. It’s in these suspended moments that emotion arises, true, raw, effortless.

Photographing someone is about sharing vulnerability, even silently. This intimacy creates a space of trust where we can truly meet. I always try to give the body time to settle, the gaze to open. It’s these simple gestures, this palpable humanity, that move me and that I attempt to convey in my images.