The Instant of Change is a project in collaboration with Rexa, Quadro Design and Ceramiche Caesar.

These are hard times for change. We live in an eternal present. We wish it to last as long as possible, but we don’t want to feel its duration. We want the “now” to always be the right one. “The moment in which things happen”. Kairos, the Greeks used to call it. The exciting, full and decisive moment. But this desire is paradoxical, if we do not allow any moment to take us elsewhere. If we do not open the doors to risk—even to pain. What would happen if we stopped being afraid of endings? Perhaps, if we allowed them to guide us beyond, we would discover a full range of new beginnings. Because the only true ending lies in stillness.

There is a well-known meditation metaphor that suggests imagining ourselves standing still in front of a busy street. Each car is a thought that we must recognise as such and let go, without wondering where it would take us. This serves to empty the mind and find some inner peace. But outside of the metaphor, that car has to be followed. Otherwise, it will remain just a blurred image that we will never be able to focus. Only by running at its own speed, we will discover where it can take us. If thoughts simulate movement and immobilise us on the side of the street, actions take us far away, even when it is foggy and there seems to be no horizon. So that’s it: with life you have to do the opposite of what you do with thoughts.

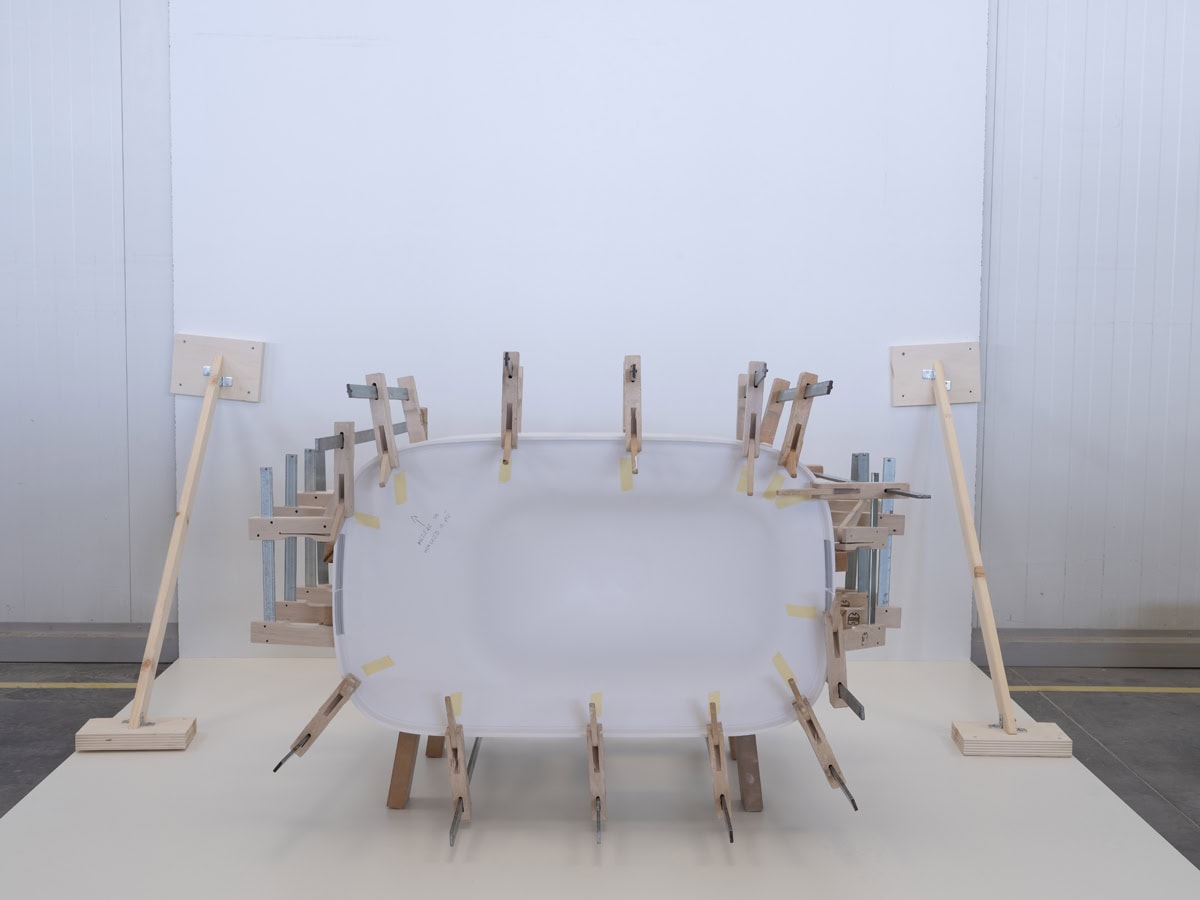

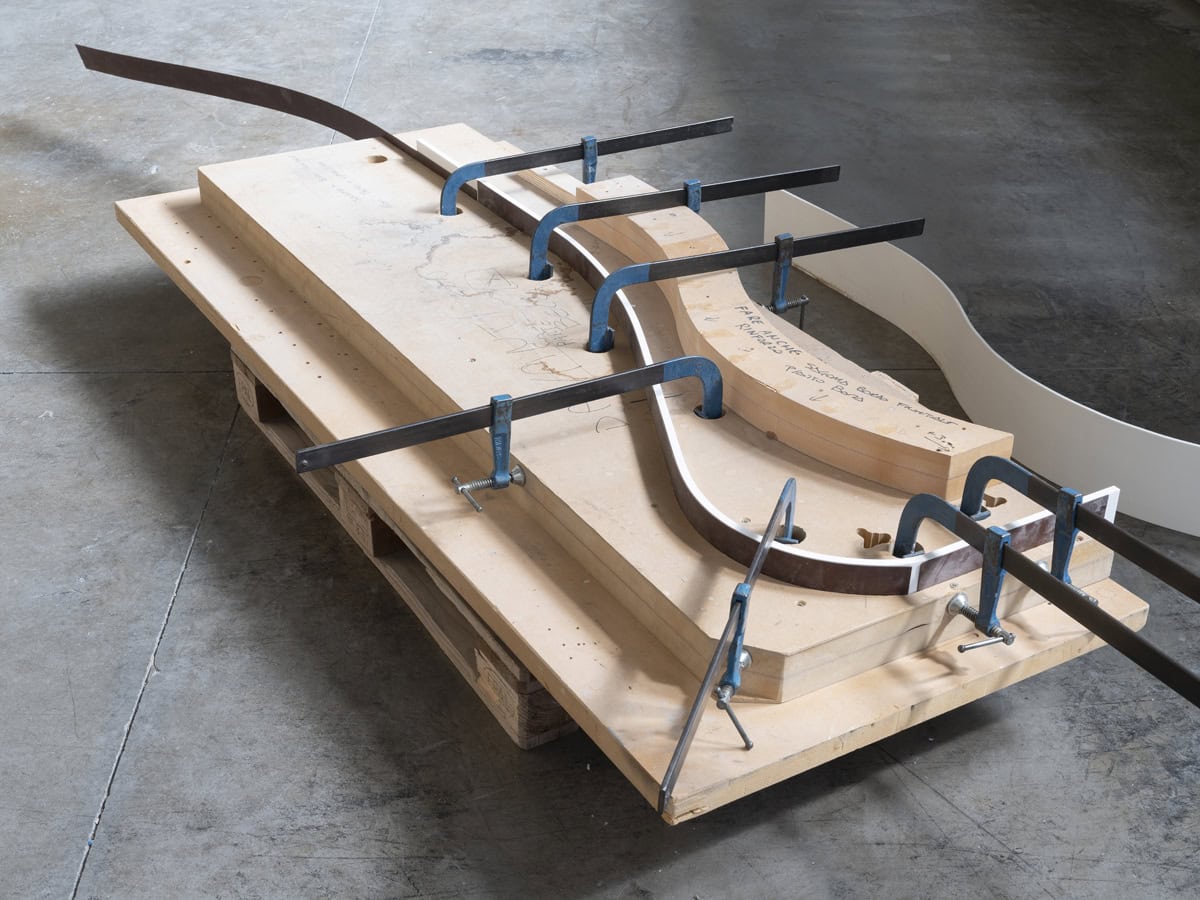

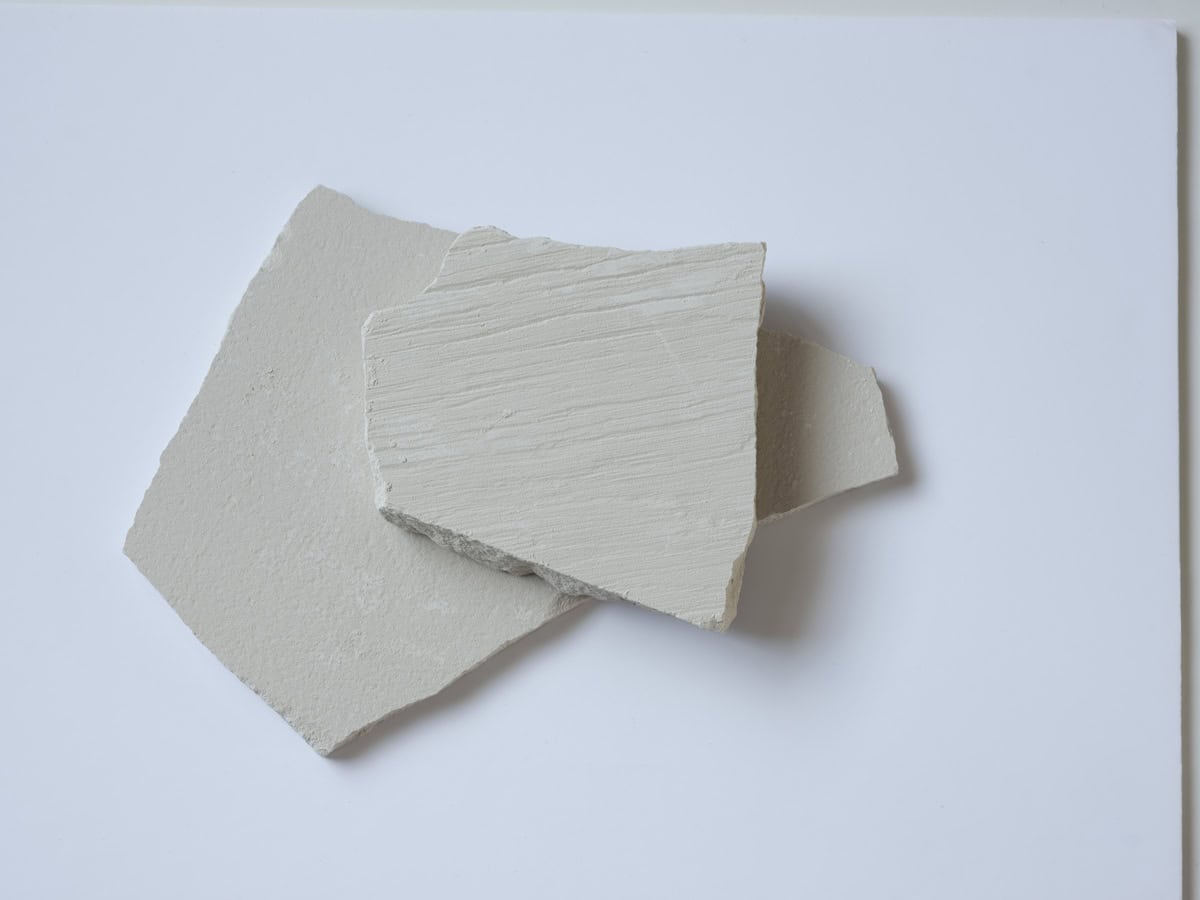

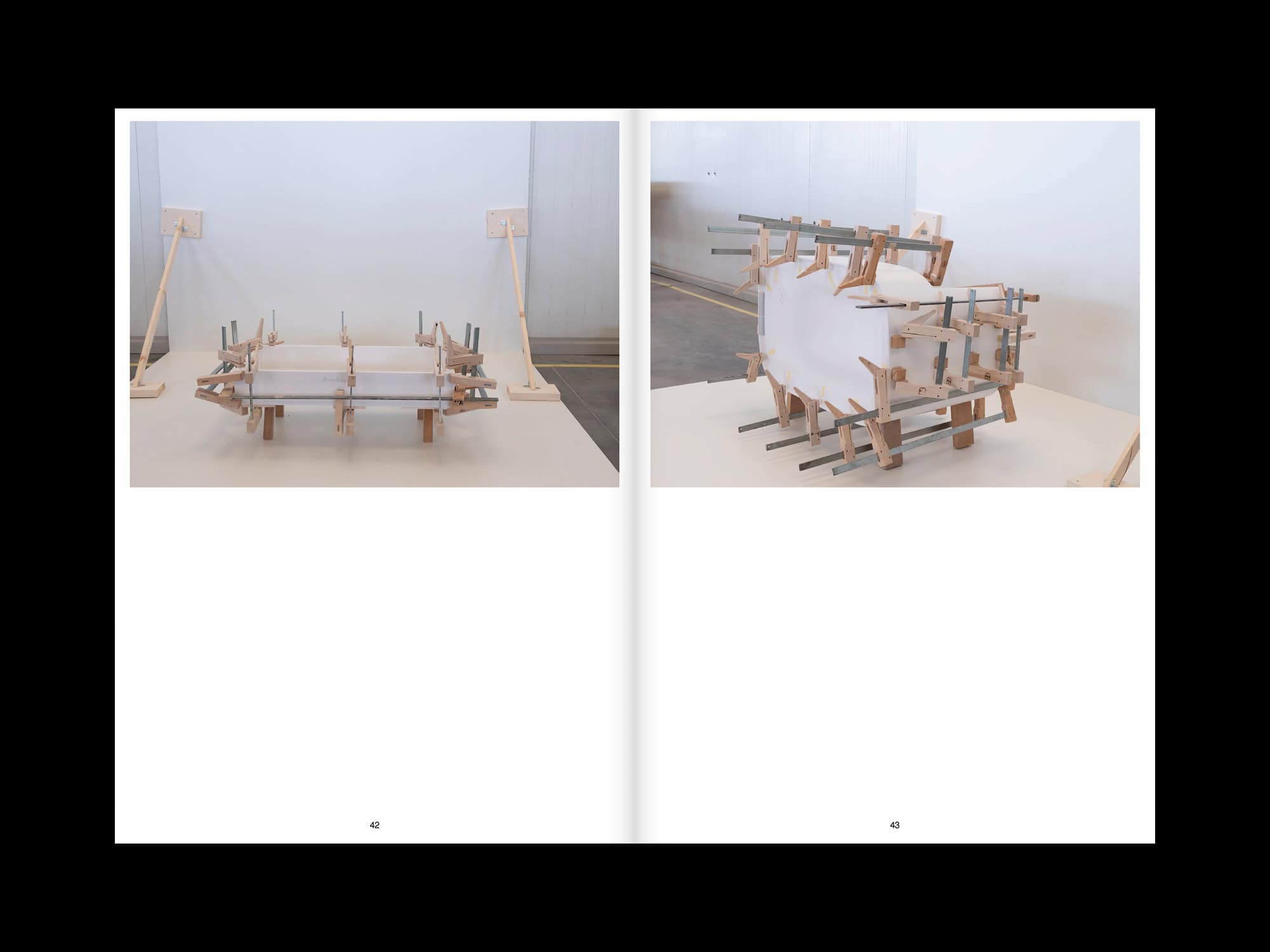

The Instant of Change is a research into the transformation of materials. But also an investigation of the processes that give life to the project. Beyond that, there is a whole world ready to be shaped.

ROBIN SARA STAUDER: “The instant of change” seems almost a paradox. How do you represent what is changing, without interfering with the change? How can a static image translate a dynamic process?

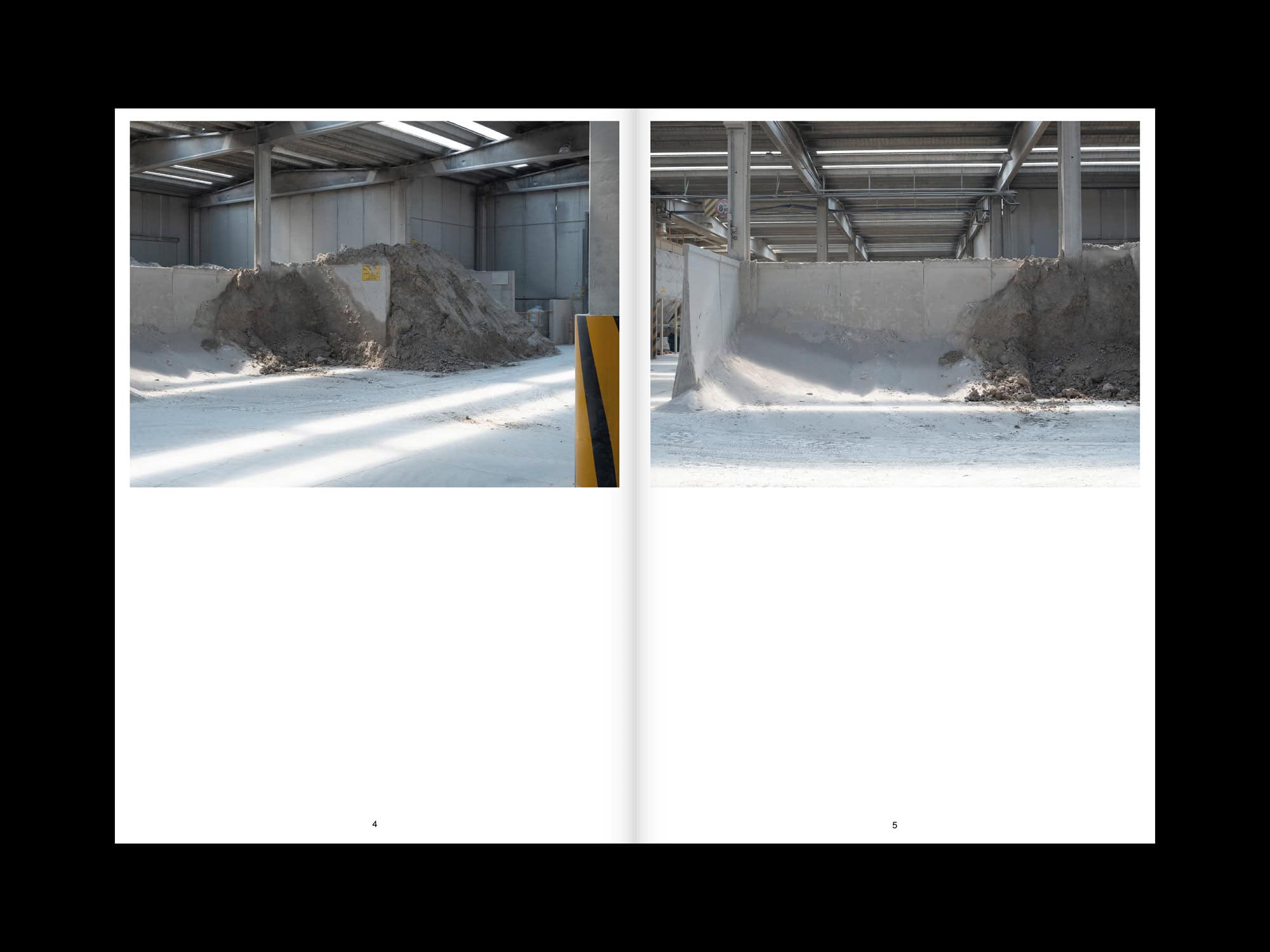

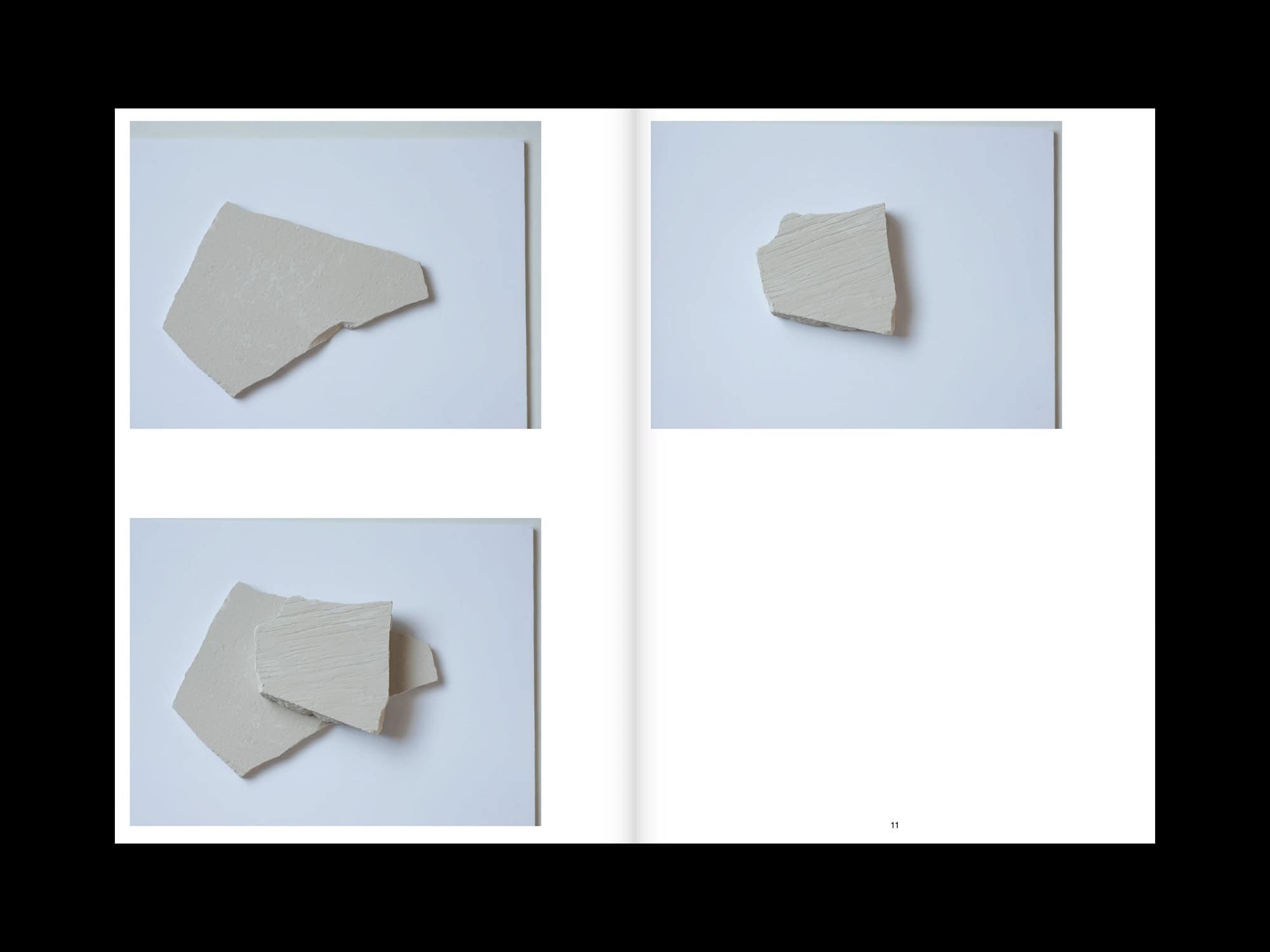

ALESSANDRO FURCHINO CAPRIA: “The instant of change” is a difficult concept to define. The moment you recognise it, it means that the change has already taken place. In a way it is a paradox, as you say. We never realise the passage, only the new position. And the analysis of that passage can only be made once the change has taken place. It is a bit like waking up and realising what has been and the new condition we are in, but not how we got there. In this, the instant of change is something unrepresentable. The only thing you can do is to try to recount a moment, only to discover in retrospect that it was indeed the moment when something changed, but the truth is that it could also be the moment when everything had already changed. So what I did was to explode the production process into a timeline of moments in sequence with each other, with the idea that not the individual, but the sum of them, could represent that transformation. The representation of what is changing is therefore definitely an overlapping of moments-elements. The change is defined through a series of steps, which cannot be synthesised in a single step. I have therefore used the sequentiality of the images and the repetition of the objects to reconstruct, in part, this timeline. The creation of a product, whatever it may be, is in any case the sum of a number of steps, each of which defines a change—or, if you like, the instant of change. What is certain is that I cannot see change as a sudden revelatory event. It is always a process, often started much earlier than we are able to see. As far as I am concerned, the project was an attempt to identify a moment, which is inevitably part of this timeline. In the very instant you try to represent it, however, it has already happened and in that it is already a memory, therefore subject to different narrative nuances. The idea was to go into these companies to tell the story of the processes behind them and to make it clear that somehow every finished product is first thought of, designed and transformed—but in a way it has always existed. To conclude, a phrase by Francesco Zanot comes to mind, in his introduction to the second edition of Kodachrome (2012, MACK) by Luigi Ghirri.

“It is a question of depth, not extension. Ghirri’s method proceeds along this line, assuming that everything results from a process of stratification. In practice, he digs into his subjects as one would a bulldozer into the ground. But then he doesn’t just look dizzily towards the bottom of the chasm he has created, but at the same time sifts through the heap of material formed in the course of this action, made up of everything that was inside and is now outside.”

RSS: Stability is often synonymous with safety. What doesn’t move sustains us. But, in the face of change, transformation means salvation. How has instability become the survival strategy of the contemporary?

AFC: I would like to introduce the answer by starting with a text by Robert M. Pirsig, taken from Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

“We live in an age of upheaval. Old forms of thinking are inadequate for new experiences. It is said that it is only when you get stuck that you really learn. So instead of extending the branches of what you already know, you have to stop and let yourself drift until you come across something that allows you to extend your roots. I believe the same applies in the case of an entire civilisation. There comes a time when you need to extend the roots.”

Instability is an inevitable part of life. But it is also what gives birth to change, and therefore to evolution. Let me explain with an example. I had never dealt with plants before, but I recently learned something I didn’t know. Basically, they push their roots into the ground and enlarge them as long as there is space in the pot. Once they have reached their maximum, they start pushing upwards, throwing out branches, leaves and flowers. So if you want a plant to grow a lot, you have to give it space and soil. It is interesting to see how plants try to achieve stability by balancing roots and height—roots and growth. It is a stability that is never still, but always in motion. And so are we: we are never really still. The only real standstill is death. But our heart keeps beating, our head keeps generating thoughts…. In summary, I believe that instability is necessary to generate motion. Even at times when we feel most stable, we unconsciously generate new instability. But it is not necessarily negative. The mere fact of reading something new generates instability: it makes room for new questions, and activates a mechanism that sets in motion the search for answers. In short, instability generates transformation and, consequently—as you say—salvation.

RSS: What makes a changing material always the same? What is the relationship between form and substance?

AFC: In my opinion, what makes a changeable material always the same is its function. The fact that it has been chosen for a set of technical specifications that make it the best hypothesis for a certain type of processing, development or definition of the use of a product. The material is always (chosen for) its function. The relationship between form and substance is a timeless one. In this case, the substance is that the material does not lose its functionality, i.e. that it retains the same prerogatives that those who chose it set out to achieve in the design discussion. When you start using a material to develop a certain product, you set yourself objectives, and it is important that that material continues to respond well to them at the end of the production cycle. In conclusion, I believe that it is essential to maintain the right balance between the essence and the behaviour of things over time. A transformation, to be a transformation, must therefore be able to orient the project without distorting its essence, neither in terms of materials nor of objectives.