SONATA is an extensive body of photographic work made by Aaron Schuman in Italy over the past four years. Rather than attempting to capture and convey an objective reality, these images are consciously filtered through the many ideas, fascinations, and fantasies associated with the country and what it has represented in the imaginations of those countless travellers who have visited it over the course of centuries. Drawing inspiration from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Italian Journey (1786–1788), Schuman pursues and studies what Goethe described as “sense-impressions”, reiterating many of the introspective questions that Goethe asked himself during his own travels through Italy: “In putting my powers of observation to the test, I have found a new interest in life…Can I learn to look at things with clear, fresh eyes? How much can I take in at a single glance? Can the grooves of old mental habits be effaced?” The resulting images are curious, quizzical, and entrancingly atmospheric, conveying a foreigner’s sensitivity to details, quirks, and mysteries: cracks that spider across ancient statues and museum walls, paths that have been shaped and trodden over millennia, the piercing eyes and looming presence of saints and gods all around, accumulations of dust, bones, sunlight, and lucky pennies. Using the classical sonata form—three movements moving through exposition, development, and recapitulation—as a guide, Schuman invites us to explore an Italy as much of the mind as of the world: one soaked in the euphoria and terror, harmony and dissonance of its cultural and historical legacies, and yet constantly new, invigorating, and resonant in its sensorial and psychological suggestions.

Elena Rebecca Rivolta: This work of yours draws inspiration from Goethe’s journey through Italy in the late 1700s. Famous escape of the then-minister in search of himself and his creativity—leading to the discovery of the sea, of carnal passions, of his artistic maturity and of an unknown country that was actually intimate and deeply familiar. Do you find in his motivations all that drove you to leave?

Aaron Schuman: Sonata initially began as an attempt to explore and express my own lifelong fascination with and relationship to the foreigner’s idea or fantasy of Italy; a place that I—and countless travellers over the course of the last few centuries, including Goethe and many others—have associated with sensuality, intensity, emotion, passion, drama, bounty, indulgence, excess, artistic expression, grandeur, romance, carnality, “la dolce vita”, “il bel paese”, and so on. What particularly inspired me in Goethe’s Italian Journey was something he wrote in 1786 at the very beginning of his adventures in, having just crossed into Italy for the first time via the Dolomites, and before he’d actually experienced much of the country itself. “At present I am preoccupied with sense-impressions… The truth is that, in putting my powers of observation to the test, I have found a new interest in life… Can I learn to look at things with clear, fresh eyes? How much can I take in at a single glance? Can the grooves of old mental habits be effaced? This is what I am trying to discover”.

As a photographer, I was excited by the prospect of “putting my powers of observation to the test”, trying to look at the world with “clear, fresh eyes”, and attempting to take in as much as possible “at a single glance”. I was also aware of how doing so can often lead to a refreshingly “new interest in life”, and was interested in how Goethe saw Italy—and specifically the act of traveling within it—as both a landscape and kind of laboratory for introspection, revitalisation and self-discovery, which is an idea that has continued (for artists, writers, philosophers, tourists and travellers alike) within our culture ever since.

Lastly, when I was a child my parents were very close friends with an Italian—his name was Italo, in fact—who had emigrated to the United States and married an American woman after the Second World War. Much of his family still lived in Italy, and in the winter of 1980 some of his relatives invited my parents to stay in their small apartment in Venice for three months. I was only two years old at the time, so I don’t have any specific or genuinely concrete memories of this trip, but when I do travel in Italy—something I have done on a semi-regular basis throughout my life ever since—there are certain sounds, sights, smells, tastes and textures that immediately pull me back to that time and make me feel an intense connection to the place (as a visitor of course, not as a native). So when Goethe mentions his preoccupation with “sense-impressions” during his own journey through Italy, it really resonated with me, and made me wonder if I might be able to make photographs that could somehow capture and convey my own sense-impressions whilst traveling there, and perhaps evoke them within others.

ERR: How did this voyeuristic fascination punctuate and dictate the rhythm and stages of your journey?

AS: The photographs in Sonata were made over the course of four years 2019-22, during many relatively short trips to Italy that I made in that time. From the outset, I wasn’t particularly interested in retracing Goethe’s (or anyone else’s) specific journey, but was more interested in finding myself in various parts of Italy and wandering somewhat spontaneously and aimlessly whilst there, trying to see with “clear, fresh eyes”, be open to the “sense-impressions” that I was experiencing, and represent them as best I could via the medium of photography. I knew from the start of the project that I didn’t want to attempt to “document” or define Italy in any general or objective way—which would’ve been an impossible task in any case, especially as a foreigner—but rather to create a very personal interpretation of my relationship to and experiences of it, filtered through both the private and shared associations, histories, images, mythologies and memories that have accumulated within my own unconscious and imagination over time. So, in a sense, the journey represented here is not one that is intended to be factual, chronological or even geographical, but is instead one that is sensorial, psychological and very personal.

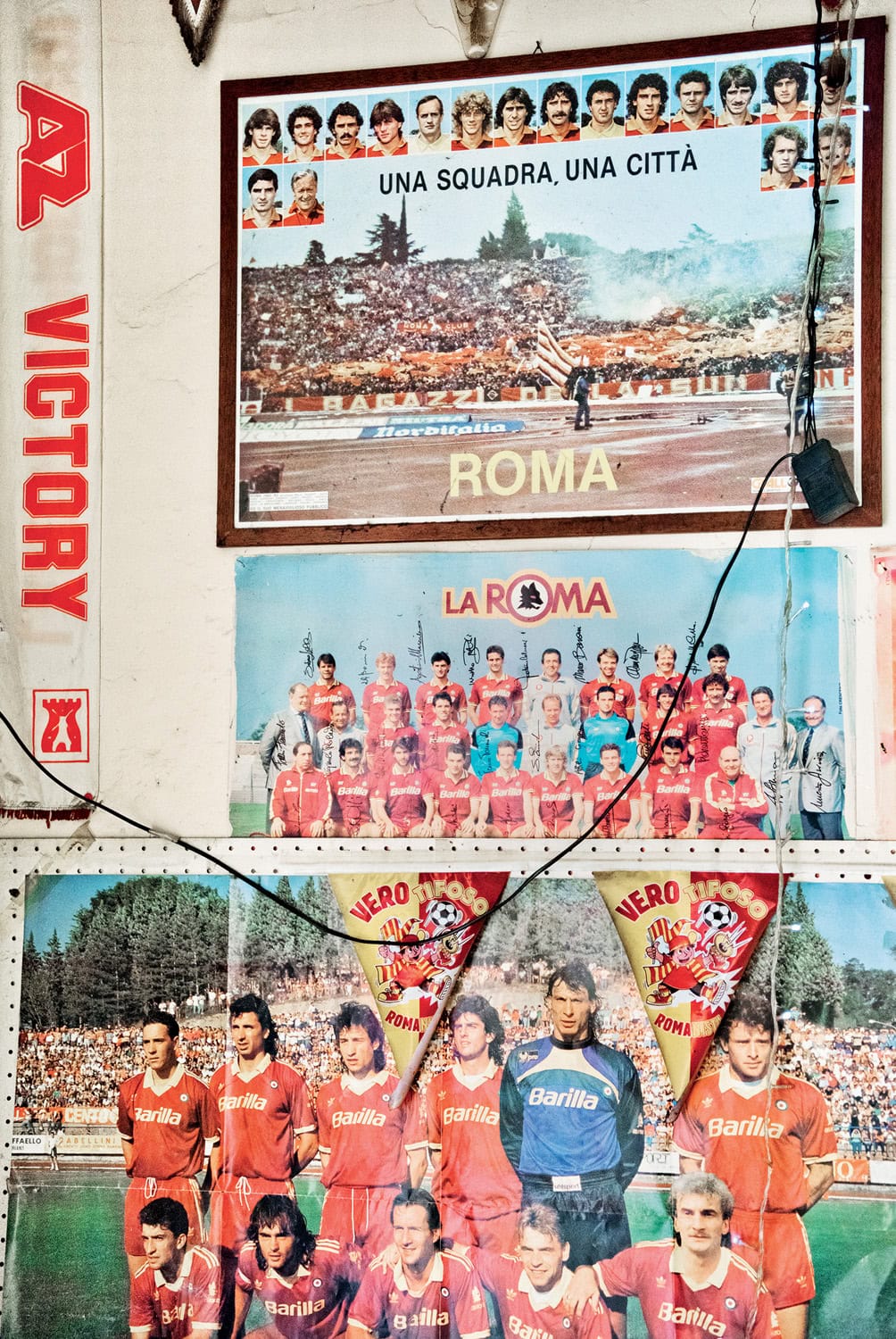

All that is to say that, when it comes to the rhythm and stages of my journey in the making of this work, these were not planned in any particular way, but were instead much more stream-of-consciousness and often based on happenstance. Over this period of time, I was lucky enough to be invited to give several talks and workshops in various parts of Italy—Naples, Milan, Emilia-Romagna, Sicily, etc.—and I would often wake up very early in the morning, or extend my visits to these places for a little while, so that I could spend time making photographs. Also, some trips were taken under the guise of family holidays; and my last and longest trip—during which I travelled across Sicily, and then gradually up to Rome, and then Tuscany—was the only one that I made with the sole intention of completing this book. Admittedly in its earliest stages, when the idea for the project was still evolving and formulating, I was purposefully going to more predictable places that are directly associated with the Grand Tour—ancient temples and ruins, museums and churches, archaeological sites and so on. But I quickly realized that what I was encountering and experiencing on my way to these places—while waiting at the bus stop or train station, or sitting at a café, or peeking into homes and shops along the way, or walking through the countryside—were just as relevant and meaningful to the work, if not more so. What I was looking for was in fact all around me; so rather than try to plan or force it, I decided that the best thing to do was simply to keep wandering, tune into my senses, and be wholly present within my surroundings, wherever that may be.

ERR: The Italian term Sonata indicates, in musical language, an articulated instrumental composition. Leafing through your pages and gliding through the images one can indeed perceive different paces, marked by precise moments and contrasts: such as the change from color to black and white or the change of paper texture. What is the sound of your images and how does it transform?

AS: Because I was interested in situating this work within the world of “sense-impressions”, as well as trying to capture and evoke a range of sensations through the images, I was spending a lot of time thinking about the relationship between photography and other mediums, especially those that engage senses other the sight. I find music especially fascinating because it’s so immediate and effective at tapping into our deepest emotions, yet it’s so difficult to articulate or explain exactly how or why it affects us in these ways. Why are particular combinations of sounds, tempos, rhythms, harmonies, melodies, repetitions or deviations, capable of making us feel the full range of human emotions—happy, sad, calm, anxious, excited, peaceful, surprised, lustful, mournful, angry and so on—in all of their complexity. Music is essentially an artificial and abstract thing, yet when we hear it, somehow in the moment it’s able to circumvent our impulses to try to rationalise or understand it, and instead delves deep into our most instinctual responses and innermost feelings. I’m not sure if a photograph can ever do this—as photography is not entirely abstract, so our initial response to a picture is generally one of comprehension (what is it?) rather than emotion (how does it feel?)—but I’m hoping that the images in Sonata do each convey a kind of sound or other sensation beyond what is visible within them, and create a kind of synesthetic experience that taps into feelings as well as thoughts.

Also, in terms of the overall book, when it came to editing, sequencing and designing Sonata, I knew that there wasn’t any specific chronology or narrative that I wanted it to convey, but I did want it to have some sort of structure or flow, so that going from the first to the last page felt like a journey or experience for the reader. I began to research various ways in which musicians and composers structure their compositions in order to create such an experience, and came across the classical “sonata form” within music theory. In “sonata form”, the piece of music is structured as three movements. The first movement is called the “exposition”, which is where the composition’s underlying themes, motifs and tonal materials are presented and established. The second movement, the “development”, is where the composer then goes in very different direction, often introducing quite a bit of experimentation, and entirely different themes, motifs and tones are presented and explored, which diverge from those in the first movement. And then in the third movement, known as the “recapitulation”, the original themes, motifs and tonal materials from the first movement are revisited and re-explored, but are presented and harmonically resolved in entirely different or newfound ways—i.e. through changes of tone, key, tempo or otherwise.

Sonata loosely borrows from this classical music form in the sense that it is presented as three chapters or “movements”—the first movement introduces a number of important themes and motifs, and is presented with one image per double-page spread, in colour, on a slightly heavier-weighted paper; the second movement diverges from this, exploring olive groves and the natural world in a very different and intentionally dizzying way, with two photographs presented side by side within each spread, entirely in black and white and on a matte paper; and the third movement then revisits some of the original themes and motifs from the first chapter, again in colour, but presents alternative variations on rather than repetitions of them, so that the overall tone and feel of third movement is very different from that of the first, even though it bears a close relationship to it. My hope is that each individual photograph will evoke a feeling or sensation within the reader, and at the same time the composition, sequence and structure of the book in its entirety will create a rich and complex experience or journey for the reader, like that of listening to a piece of music from beginning to end, which in some way represents my own experiences and sensorial journey through Italy.

ERR: Sticking with the musical theme, you made a Sonata through images. What music did you listen to along the journey? Was there anything particularly meaningful that accompanied you in the making of this work?

AS: I listen to all kinds of music all the time, but before this project I had never really explored classical music in great depth. That said, my parents constantly listened to classical music throughout my life—the radio was always on, and I spent many very long car journeys in the backseat of their car, the speakers behind my head blasting out all sorts of symphonies and sonatas and arias and operas—so much of it is vaguely familiar to me, even though I never really consciously engaged with it. When I settled on the sonata form for the structure of this book, I did begin to listen more closely and carefully to a quite a few sonatas—mostly by Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, and some Strauss—just to try to get my head around how sonatas work and sound, and what emotional effect they have; but to be honest, my tastes in music is generally more contemporary.

I was asked a similar question in an interview in May 2020—it the midst of the strictest Covid-lockdowns in the UK—and replied: “Music-wise, I’ve found myself gravitating towards things that are dense, multi-layered, and melodic, but tend to have heavy bass lines…I’ve found myself revisiting TV on the Radio quite a bit—in the 2000s I was really into them, but almost forgot just how incredible they are. If I had to choose one song, I’d go with the opening track to their second album, I Was a Lover”—which, re-listening to it today, I now realize actually has three distinct movements, and is quite sonata-like in form.

Lastly, as a teenage of the early-90s, I have a soft spot for music that often falls into the categories of “grunge” or “shoegaze”, and at the beginning of this project I was doing a lot of research into Italian bands along those lines, hoping I might be able to see some of them during my travels. I was excited to come across a scene often referred to as “Italogaze”—bands like Stella Diana, Human Colonies, Rev Rev Rev, and Tiger! Shit! Tiger! Tiger!—and in fact, when I was just beginning this project, the working-title I used for the earliest drafts and PDFs of the book was Italogaze. Then in 2019, I was invited to give a talk about my previous book, Slant, at Marmo—an excellent bookshop in the small city of Forlì, in Emilia-Romagna. Afterwards, I was talking to a few of the photographers that had come to the talk, and they asked me what I was working on next; when I mentioned that I was making something called Italogaze, their jaws dropped. Firstly they couldn’t believe that, as an American living in England, I knew anything about that scene—and then they went on to explain that they were themselves an Italogaze band, called Mondaze. They’ve since become one of my favourite bands, and last December they released their first full-length album, Late Bloom, which I’ve been listening to constantly and is genuinely breathtaking. For a while now, I’ve been daydreaming about asking them if they might consider composing a “shoegaze sonata” of sorts that is in some way loosely informed or inspired by Sonata—I’d love to hear how they might interpret the images through their music—but I know that they’ve been very busy touring this year, and in truth, I haven’t worked up the courage to ask them quite yet.

ERR: The project is still ongoing, what upcoming outcomes can you anticipate? Do you think it is a project destined to meet an end?

AS: I definitely feel that the book itself is complete and fully resolved, and I couldn’t be happier with it in terms of book format, but I’m also excited about the prospect of presenting this work in other forms as well. Throughout the making of Sonata, the amazing Giulia Zorzi—of Micamera in Milan—has been such a great friend and supporter of the project, offering so much guidance, feedback and insight. In fact, we had planned to have an exhibition of some of the earliest work, alongside associated materials and ephemera, at Micamera in mid-2020, but that wasn’t able to happen for obvious reasons. So we are now planning an exhibition of Sonata at Micamera in 2023, which will open in late January and run into the spring. I’m really looking forward to discovering how the photographs will transform and gain new impact and meanings for an audience on the wall, as well as exploring how the project as a whole will evolve and grow within this unique gallery context, and hopefully within other spaces and contexts as well in future.

Furthermore, making this work has been one of the most intense, freeing, life-affirming and rewarding creative experiences of my life, so I fully intend to continue to make photographs and explore every corner of Italy with camera in hand for the rest of my life—honestly, I could spend all day, every day, doing this and never get bored. So perhaps there will be a “Sonata No. 2” further down the line; but it’s more likely that any future works will probably take on a different form or direction. Whatever the case, I really hope that at least this creative process and experience isn’t destined to end anytime soon, and will be welcoming any and all opportunities to return to Italy to continue it with wide-open arms (and eyes, and ears and so on).

ERR: Et in Aracadia ego: The book closes with this memento mori, one of the most enigmatic phrases in art history. Recollection of a joyous life in sublime land, inextricably linked to an end, addressed to a time now past. Would you like to reveal what this sumptuous and perhaps apparent conclusion means to you?

AS: This curious phrase became especially popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and was used or referred to in many works of art and literature during that time. In fact, Goethe uses it as a subtitle or motto in his own Italian Journey. Directly translated, it reads, “And in Arcadia am I”. In the most literal sense, it can be interpreted as a simple autobiographical declaration—“And I am in Arcadia” with Arcadia being a pastoral idyll or mythical paradise, an unspoilt wilderness where nature and humanity are in harmony. Yet many of the historical artworks and of pieces of literature that invoke this phrase make allusions to death and mourning, and another common interpretation of the phrase is that the “I”, rather than being autobiographical on the part of the author or artist, refers to Death itself—i.e. “And [even] in Arcadia, I [Death] am present”.

During the time in which I was making this work, my father’s health rapidly deteriorated, and he eventually died in October 2020—unfortunately, he was never able to see the complete Sonata. So throughout the whole process—and despite the fact that I was having the time of my life being preoccupied with sense-impressions, and exploring and inventing this imagined Arcadia while photographing and travelling through Italy—I guess that my dad was always in the back of my mind as well. When it came time to edit the book, I discovered that alongside many of the more sensuous or life-affirming images I’d made, there were quite a few darker, starker, and more disquieting or melancholic photographs as well, which alluded to feelings of danger, fear, terror, trauma and death itself. I quickly realised that by incorporating these images into the edit and sequence, it heightened it, and introduced a kind of “chiaroscuro” effect within the book as a whole—contrasting lightness and darkness, ecstasy and despair—adding greater depths and dimensions, and allowing it to represent more fully the broad, multi-layered and complex spectrum of sensations, feelings and emotions that define human consciousness and experience. So I closed Sonata with this motto, once again borrowed from Goethe, in order to hint at the double-edged nature of the work itself; it’s both celebration of the euphoric joys, sensations and wonders of life, and at the same time a reminder that life itself is never perfect nor eternal. And in Arcadia am I.

Aaron Schuman (b. 1977) is an American photographer, writer, educator, and curator based in the UK. His photographic work has been exhibited internationally, at Tate Modern, Christie’s, Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Etnomuzeum Krakow and elsewhere. He is the author of two critically acclaimed monographs: SLANT (MACK, 2019) and FOLK (NB Books, 2016). He has curated several major festivals and exhibitions, and was the founder and editor-in-chief of SeeSaw Magazine (2004–2014). Schuman is Associate Professor and Programme Leader of the MA Photography programme at the University of the West of England (UWE Bristol).