Peter Watkins was born in 1984 in UK and is a visual artist based in London. Watkins’s autobiographical work begins with photography, but incorporates sculptural and spatial elements. His work is above all a meditation on the practice of archiving and remembering: how certain material is preserved or lost through processes of memorialisation.

About ‘The Unforgetting‘ – words by Peter Watkins:

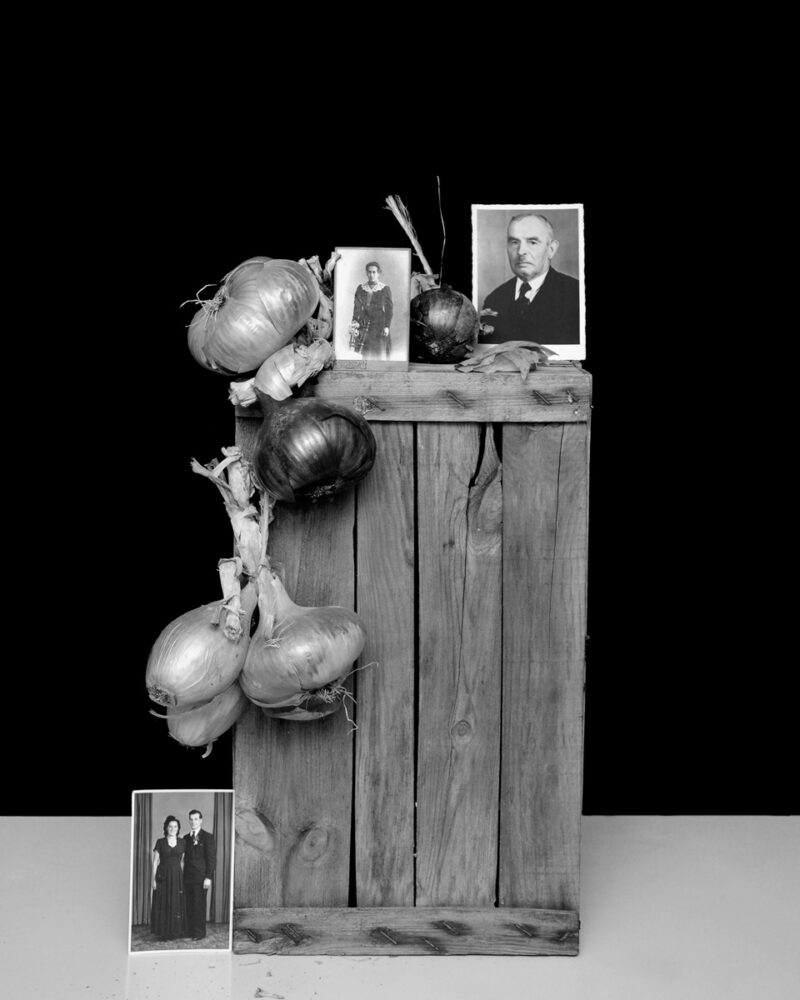

The Unforgetting is the culmination of several year’s work that examines Peter Watkins’s German family history; the trauma surrounding the loss of his mother as a child, as well as the associated notions of time, memory and history, which we encounter as bound up in the objects, places, photographs, and narrative structures circulated within the family. This is an exploration of a history that cannot be told with any objective accuracy or veracity, but rather has become a study into the fundamental questions surrounding life and death, memory and trauma, the weight and lightness of loss, and attempting to understand the universal experience tied together with the highly personal.

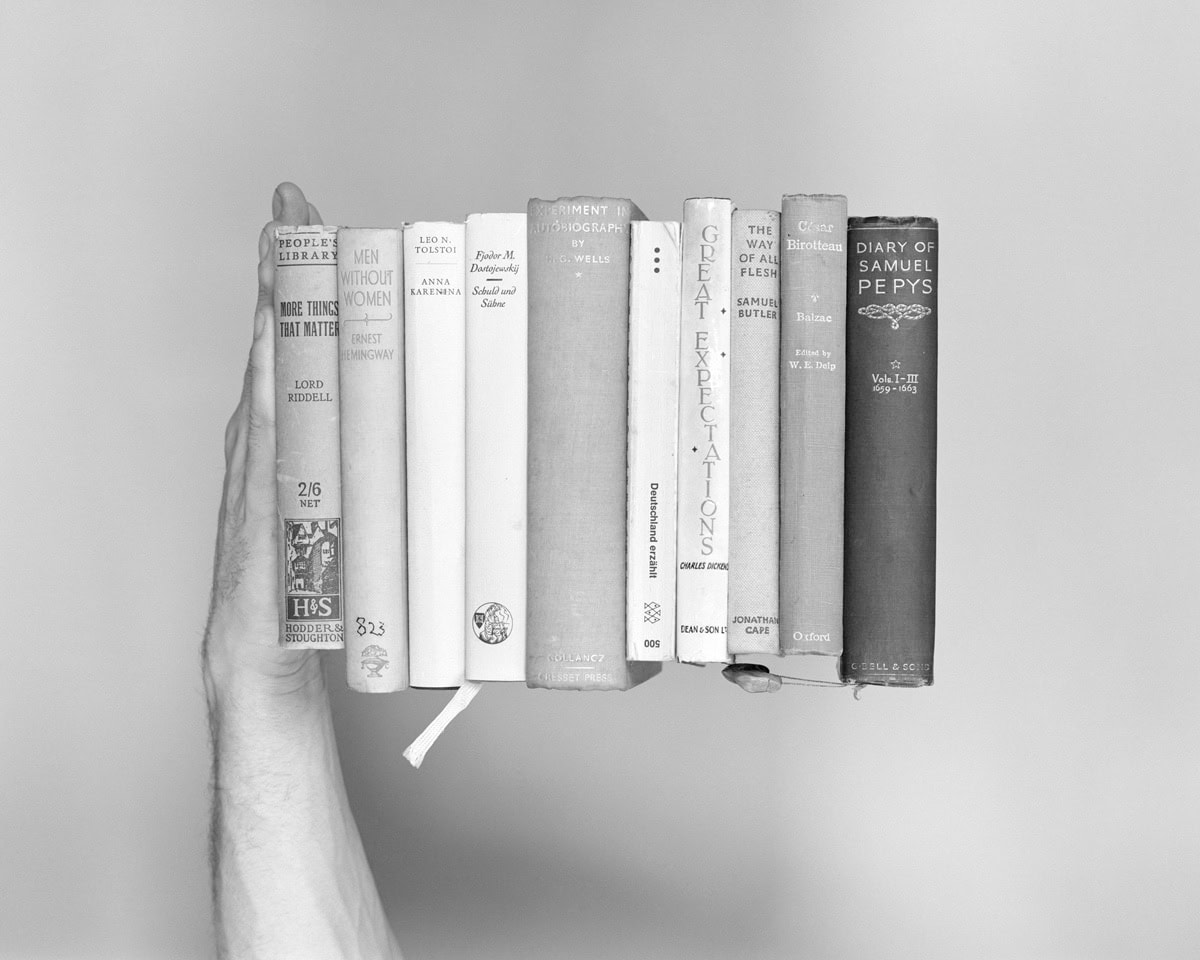

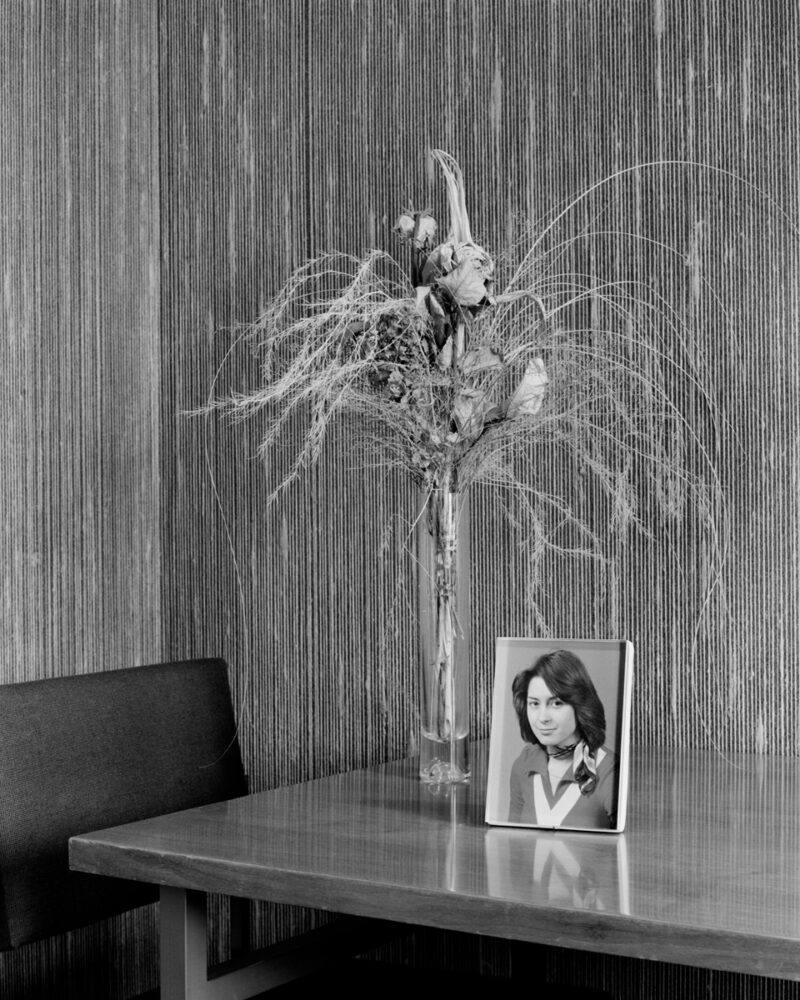

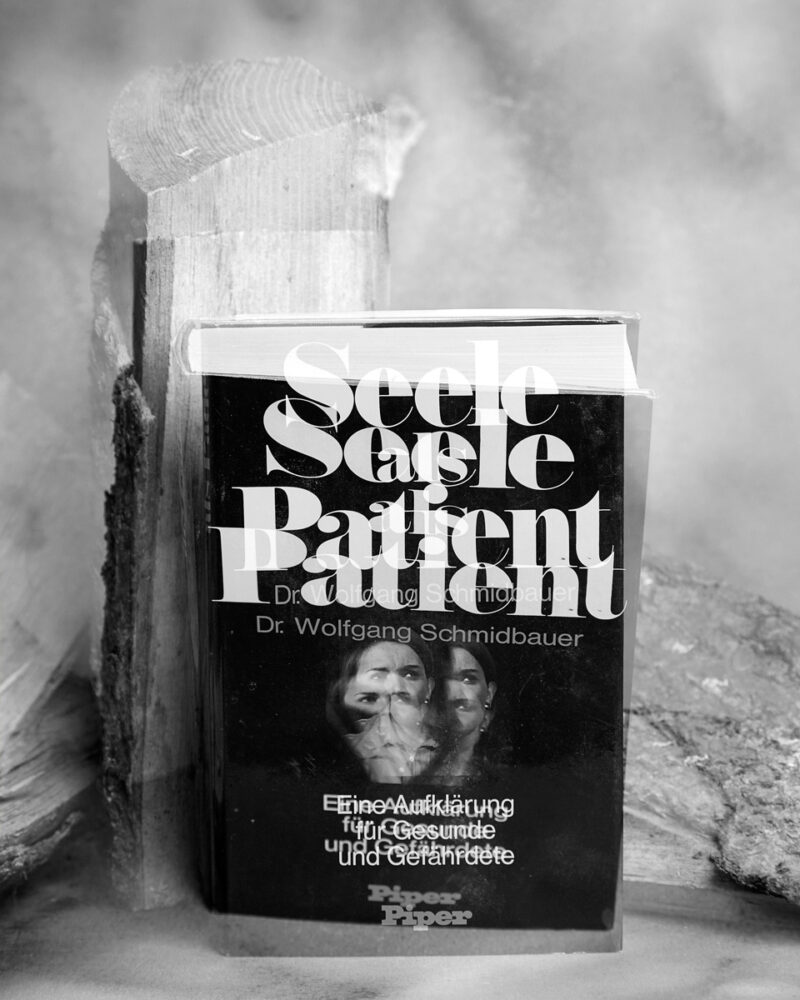

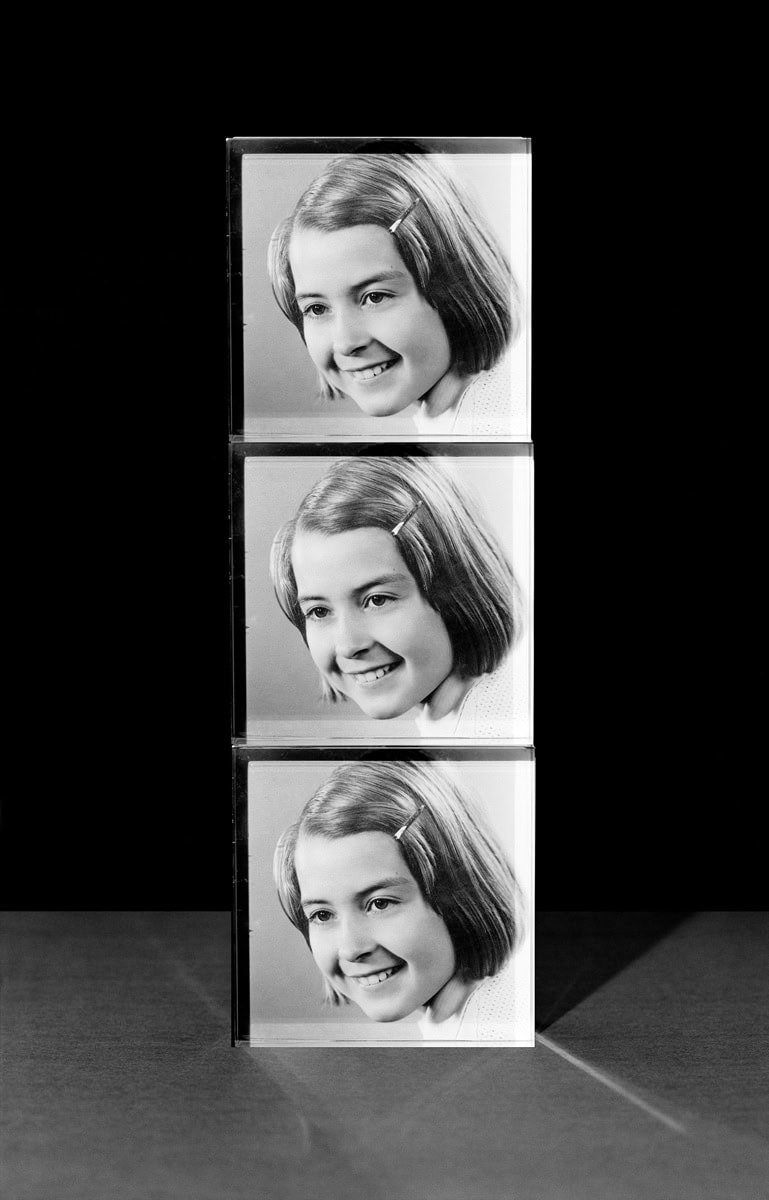

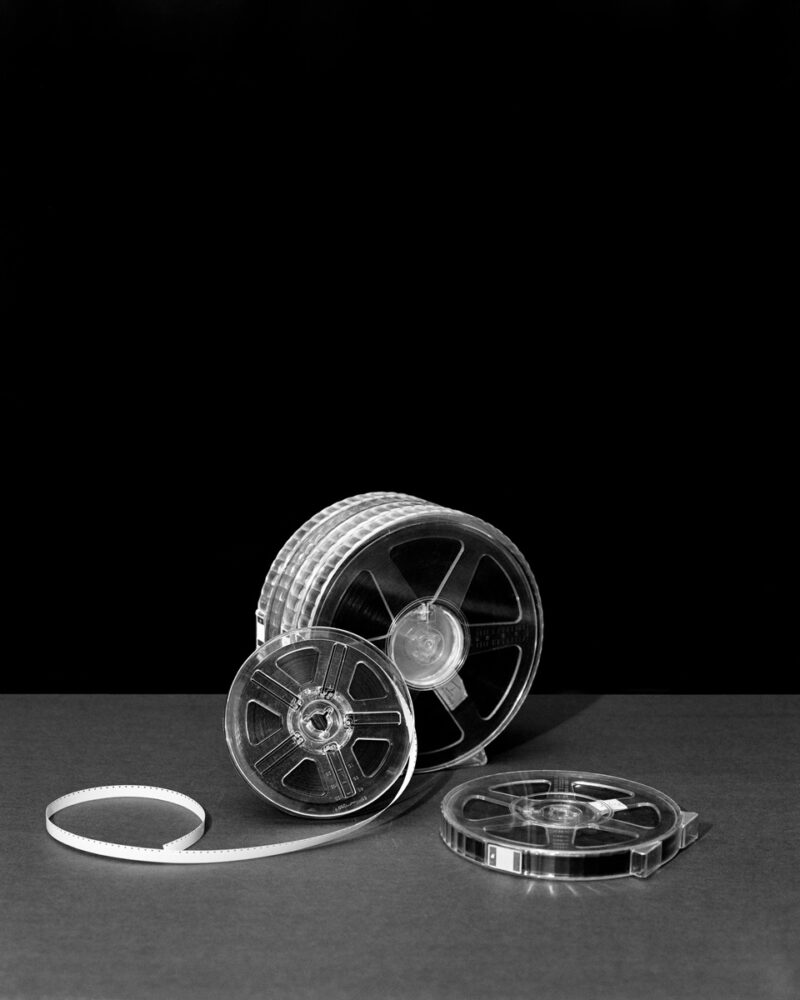

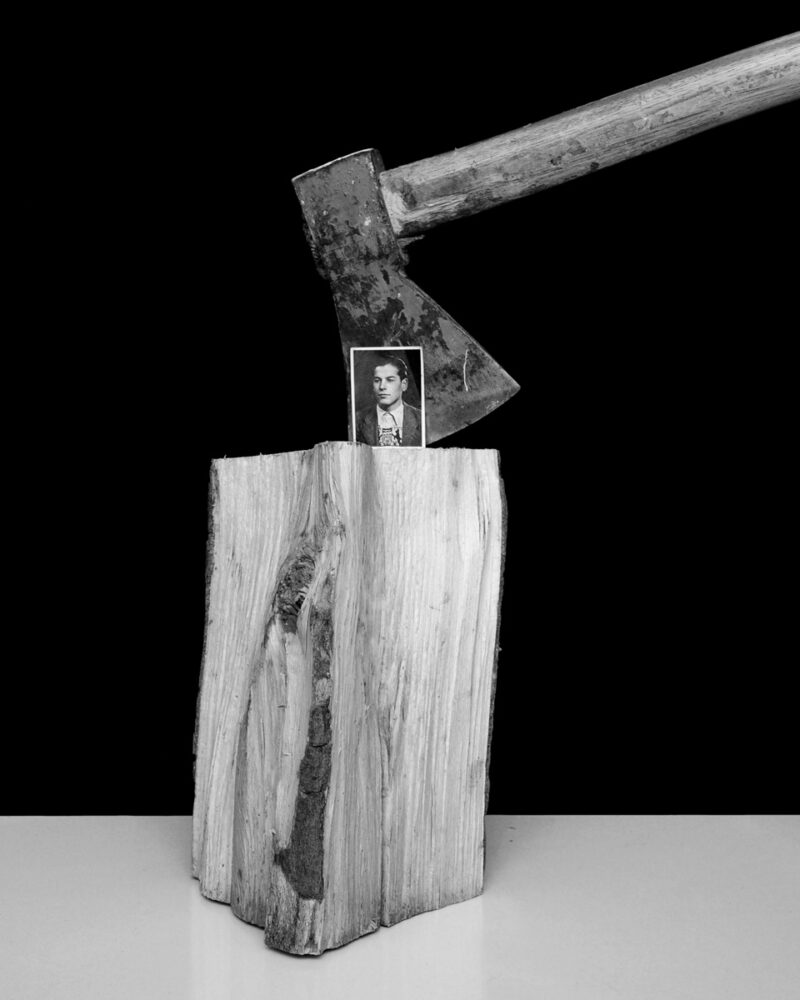

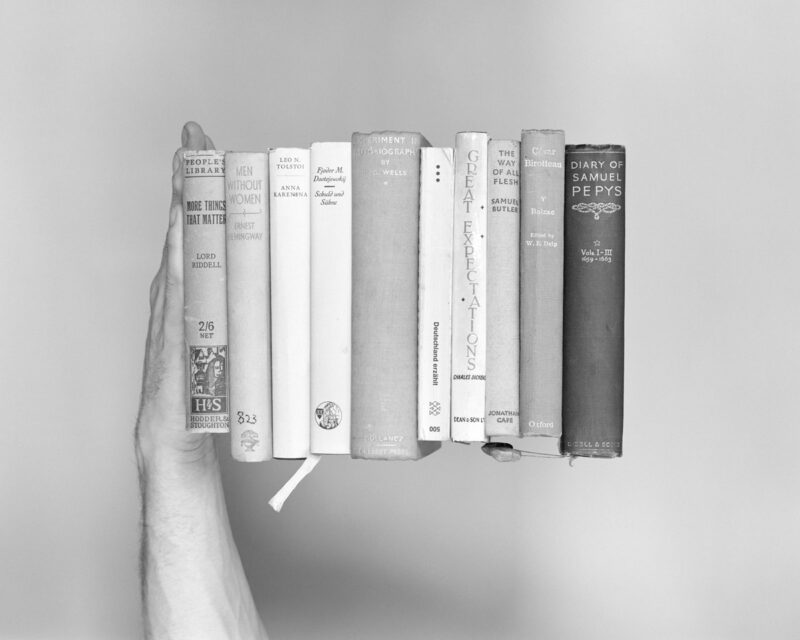

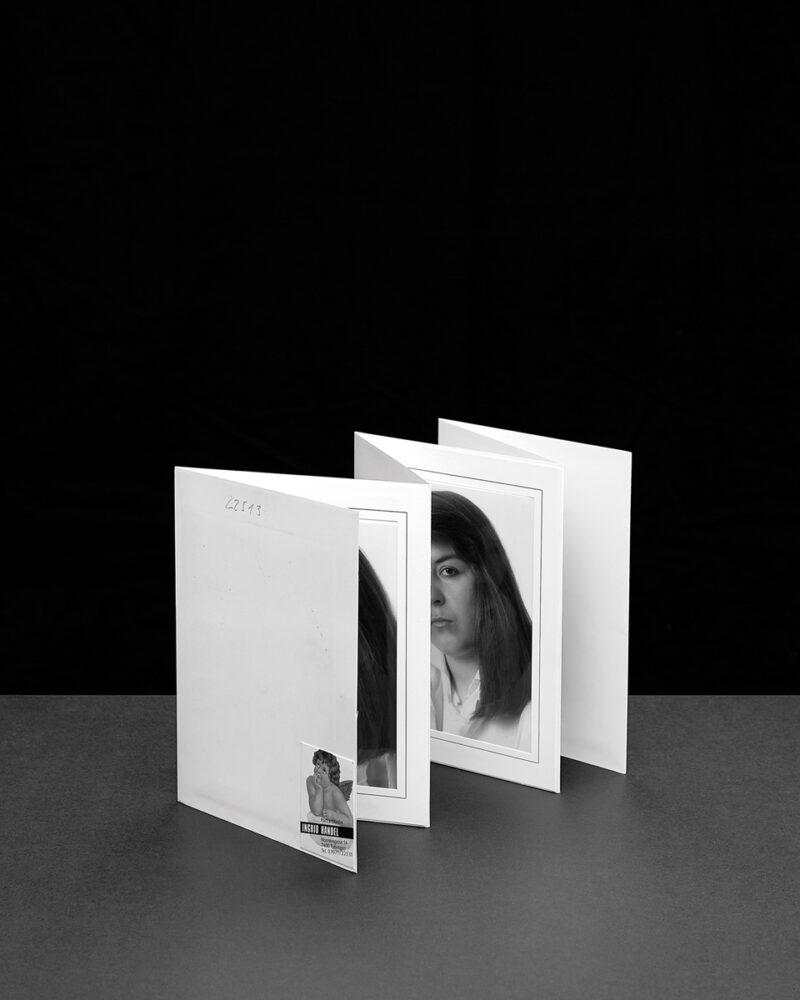

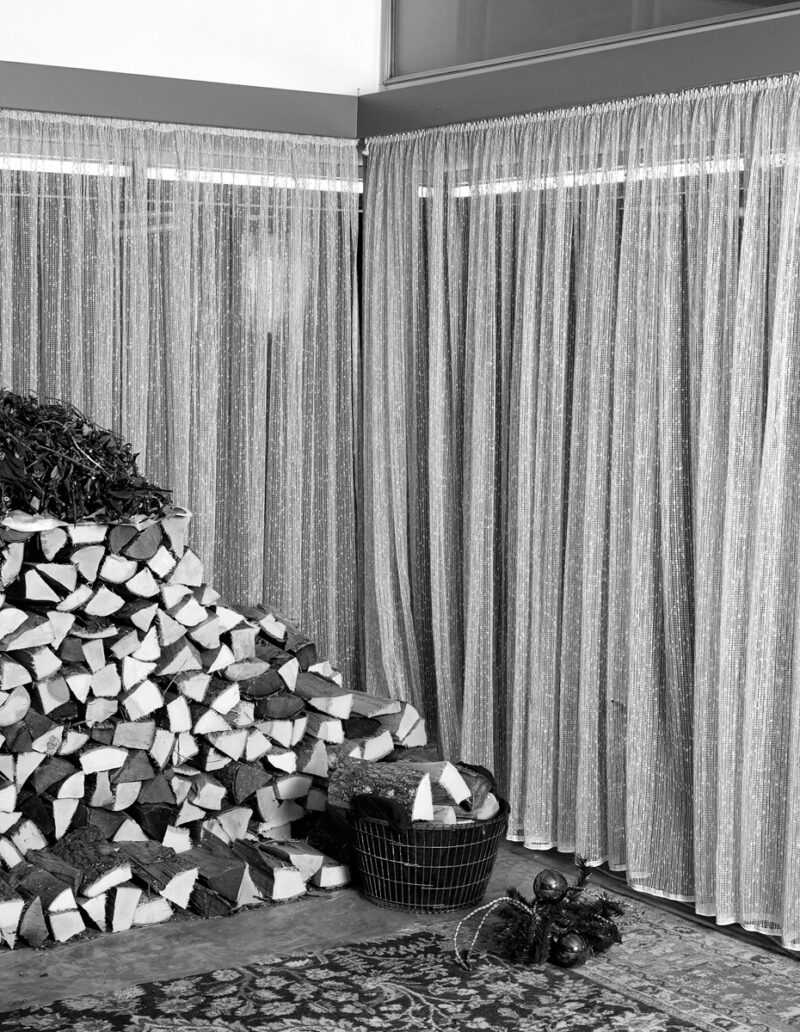

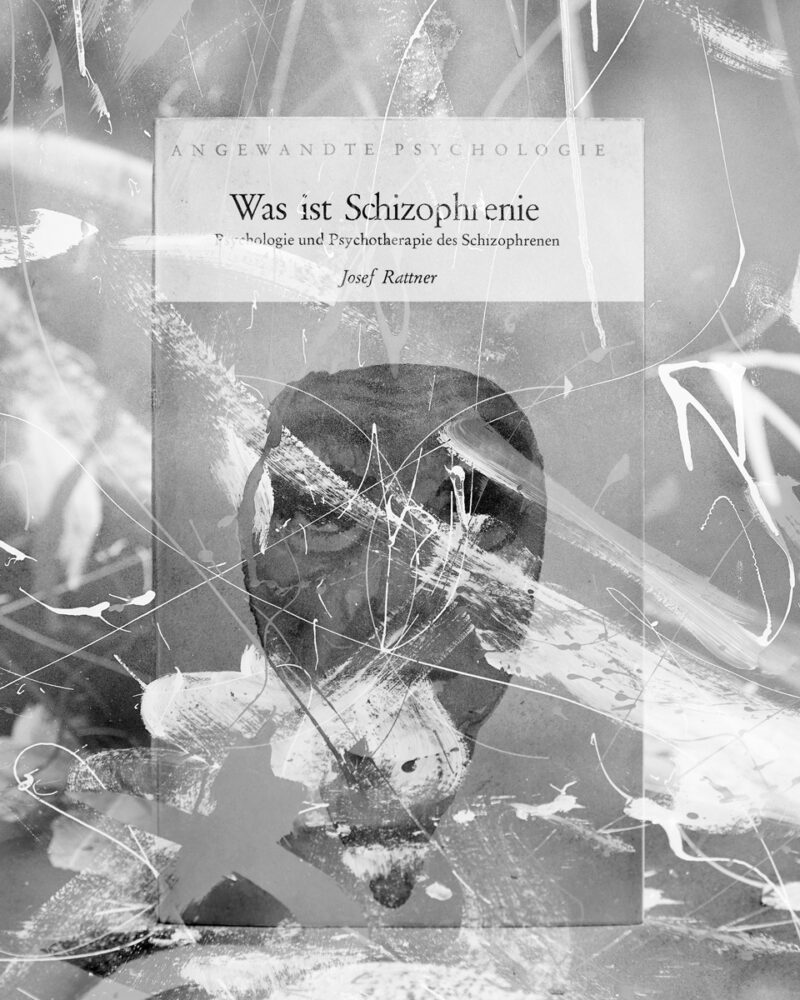

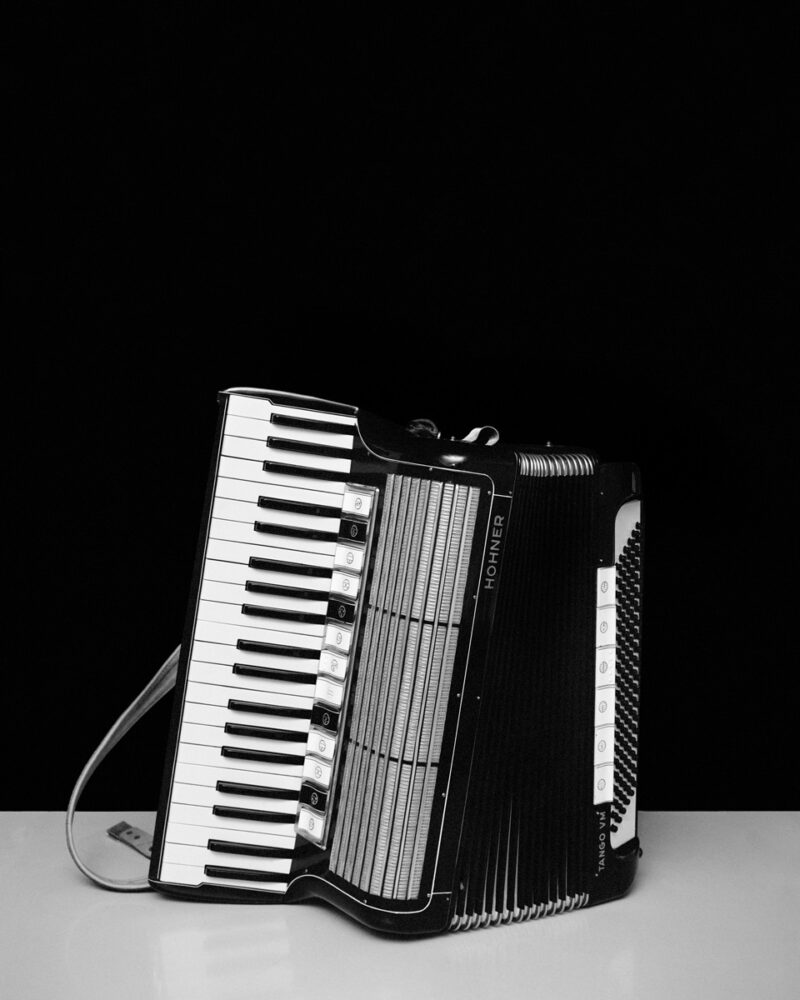

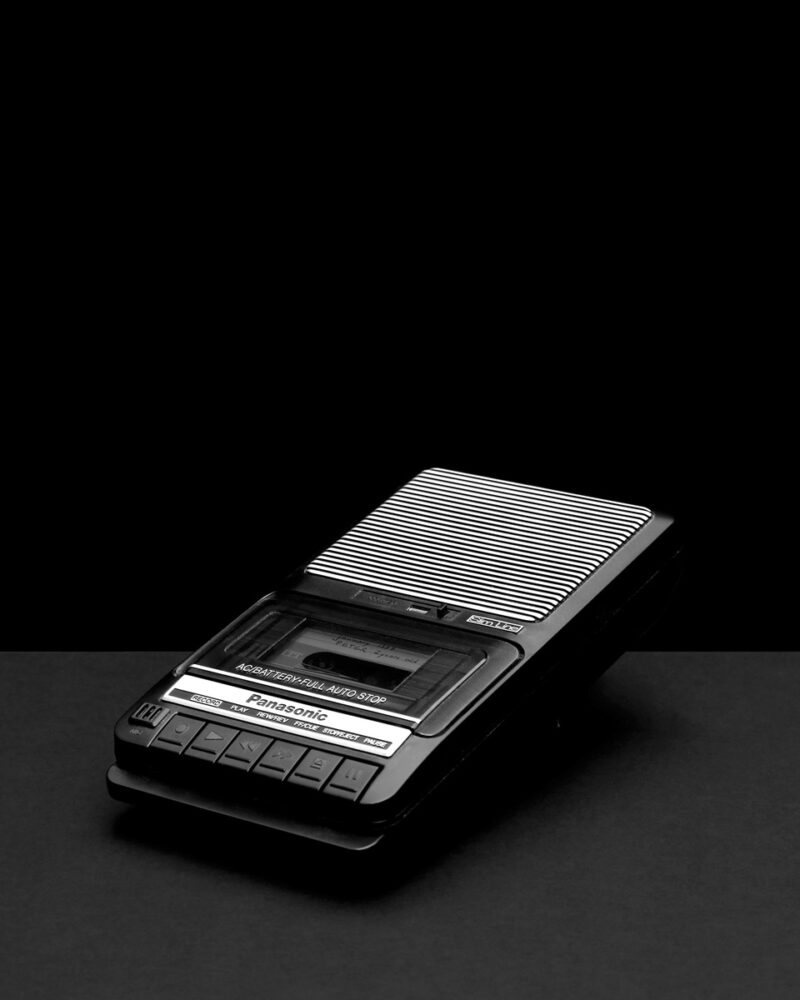

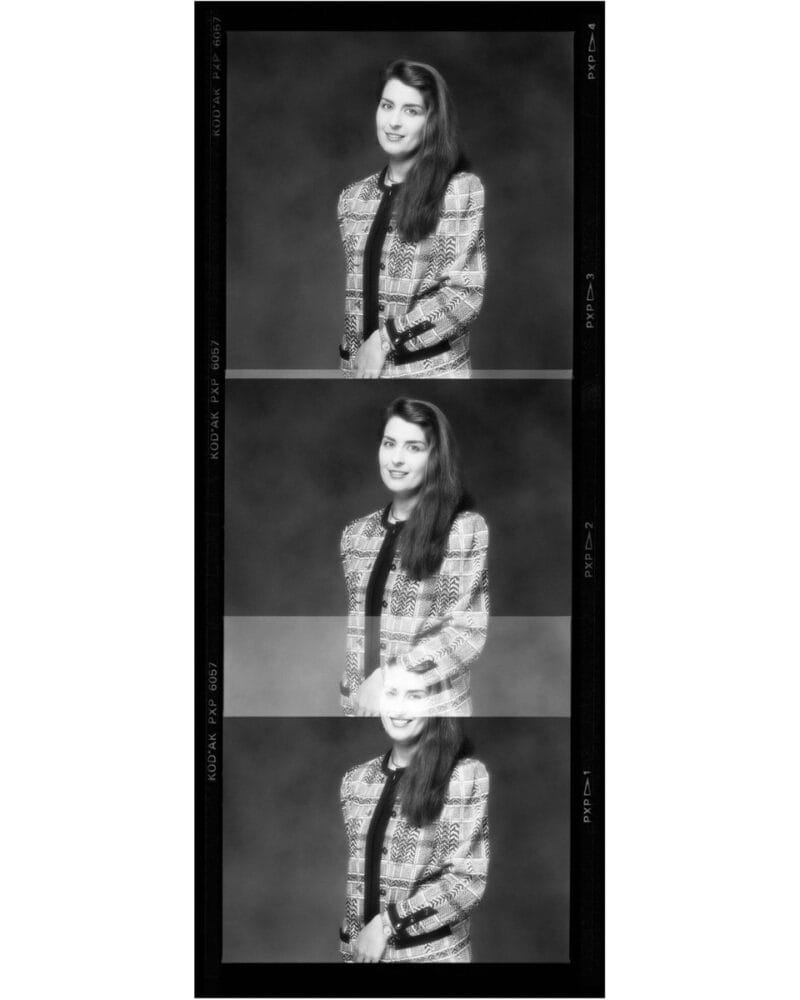

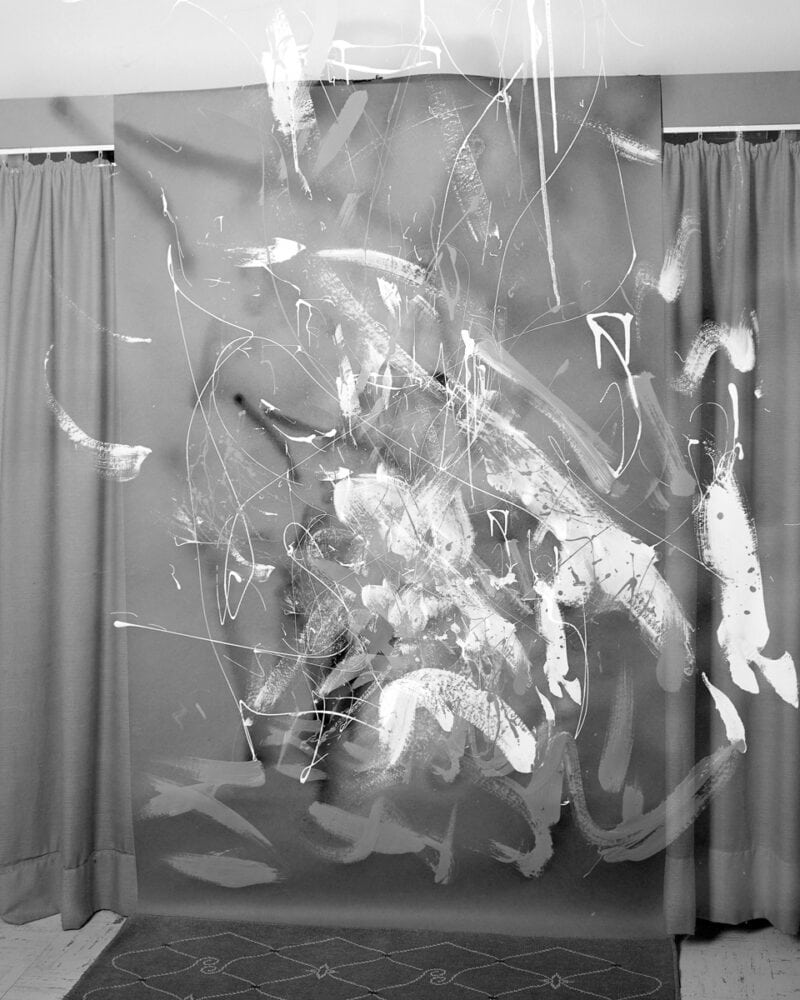

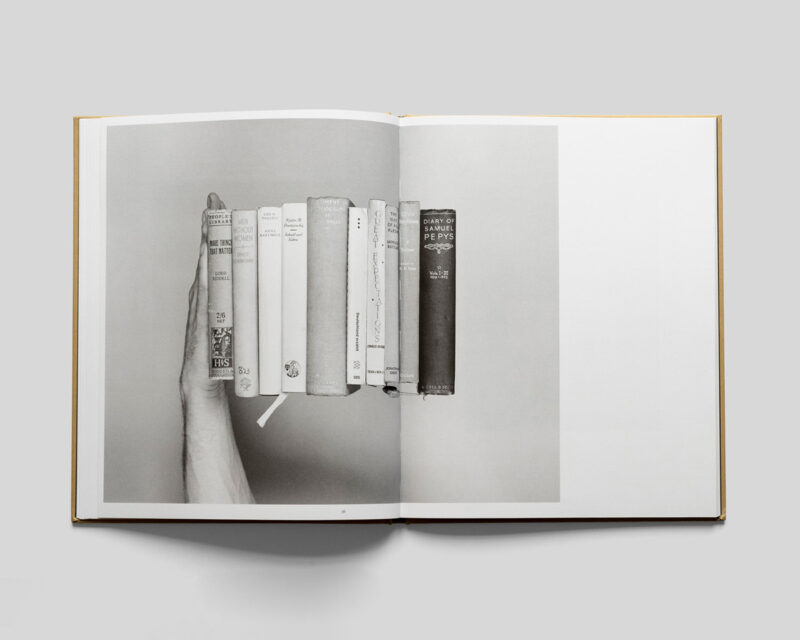

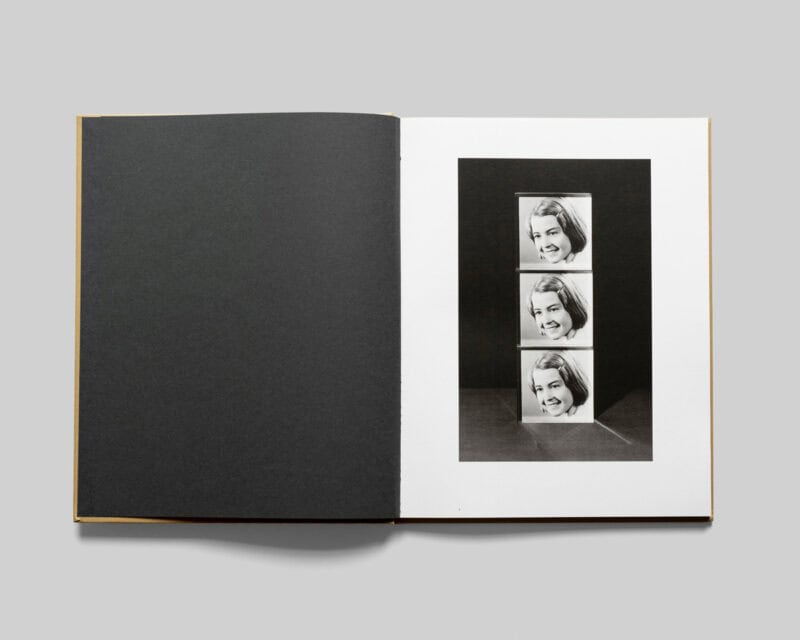

This presentation, largely of objects, carries the weight of a family history, but the personal charge with which the images are made remains undisclosed and obscured. Images of reels of Super-8 withhold the images they contain; ceremonial glasses appear transparent and emptied of liquid; a spectral baptismal dress appears impossibly suspended, and when exhibited it is glazed behind yellow glass: a wash of colour in an otherwise monochromatic series of works. The recurrence of wood throughout points towards the exploration of a rural Germanicity; but wood here also represents the passing of time, and of the “here I was born, and there I died,” as Hitchcock’s Proustian Madelaine exclaims in Vertigo, when pointing to the sawn sequoia tree. These works are universal in their unwillingness to disclose the peculiarities of their deeply personal roots; but woven beneath their surfaces are the stories and interconnected narratives that come to constitute a personal biography, and a shared patchwork of reminiscences for his mother and their shared cultural context. This series finds its core, therefore, in the interplay between presences and absences—the absence of the mother, and the traces of her life explored in states of Unforgetting.

The Unforgetting came together recently in the form of a book by the same title published by Skinnerboox and launched on the river Seine during the opening evening of Polycopies in November 2019. Watkins was the recipient of the Skinnerboox Book Award, which was subsequently selected by Mark Power, Terri Weifenbach, Brad Feuerhelm, and Sean O’Hagan at The Guardian in their end-of-year Best Books of 2019 lists. The book was subsequently shortlisted for the Recontres d’Arles Author Book Award 2020.

Below is a text that appears at the back of The Unforgetting, which at once details Watkins’s attempts to make sense of memory and it’s import on the big existential questions in life, but also acknowledges the futility of such an endeavour, and his sense on wanting to move on having spent almost a decade exploring the trauma’s surrounding the early part of his life.

I have this memory where we’re driving down a long, straight road. The car wipers are moving quickly, pushing water from our vision. Outside it’s muted grey, flat and wet; the surrounding fields and trees pass in a smudge of late-Autumnal hues. I’m sitting in the centre-backseat of our silver 1989 Volkswagen Golf, and my younger brother is to the left of me. It’s a European standard left-hand drive car, but we’re on a British dual carriageway near to where we grew up, in Monmouth, Wales. My mother is in the passenger seat on the right and my father’s driving, wearing a pair of grey creased cotton trousers and a navy merino jumper with concentric diamond pattern down the middle. We’re talking while looking straight ahead, out the front window at the grey road. Time is punctuated by the pendulum-like to-and-fro of the wiper blades on the glass. I lean forwards and ask my parents a question—the kind of direct existential question that children of only a certain age have a tendency to ask: I want to know when my parents will die. We talk about this for some time before I finally ask for their ages. My father tells me that he’s eighteen years older than my mother, something that at the tender age of eight years old, I had not foreseen. From this information, I conclude that my father will die first, and that my mother will die later.

I’ve recalled this memory so many times now that it has become dilute. What once felt like a pure and wholly lucid flash, a fragment of time taken wholesale replicated –something tangible, and real–has now become murky, and untrustworthy. Memory is coloured by recollection, and the impulse to commit it to the formal structure and rigours of writing seems corrupting, even as it reconciles. The conscious act of remembering overlays the memory with the language of narrative fiction, and further transformed through the act of retelling—indeed, this text itself has been rewritten so many times as to render it almost consciously inaccurate; its original now indistinct and restless. As Chris Marker’s narrator in Sans Soleil says: ‘I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining. We do not remember. We rewrite memory much as history is rewritten.’

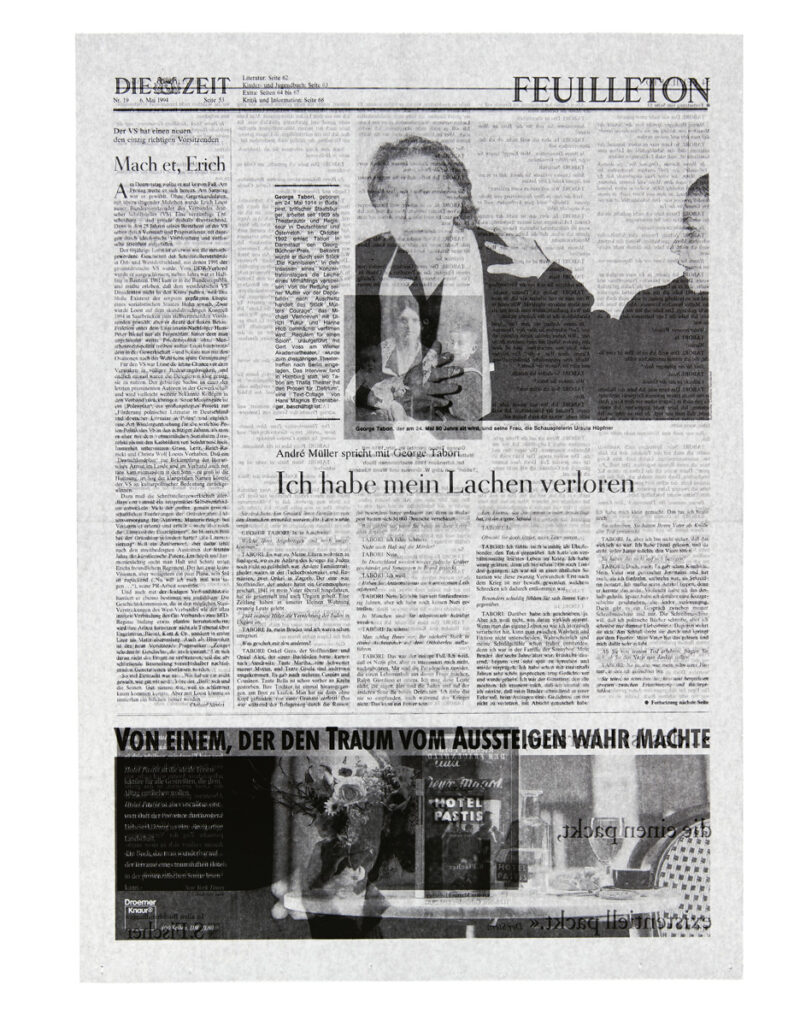

On 28th February 1993, sometime after this car journey, my mother’s body was found on the shore at Zandvoort, a seaside town in the Netherlands. She was thirty-four. She had been diagnosed with Schizophrenia in her late teens, after suffering from an episode shortly before completing her Abitur, and had experienced a relapse not long after I was born, in 1984. Between these times her health had been good, and the medication had helped her through the more troubling periods in her life. Her apparent suicide proved to be the result of a third, final episode—the culmination of several months’ struggle with the illness. In those last months, she moved between her native Germany and Wales, where we lived at that time, between different houses and hotel rooms and two psychiatric wards, as the family tried desperately to take control of her deterioration. She no longer went by her Christian name, ‘Ute’, but by ‘Suzanne’—her middle name. She was restless and manic, and seemingly heartbroken.

Zandvoort lies equidistant from Monmouth and Würtingen, where she grew up in Germany, and there is some validity to the idea that in her confusion and heartbreak she was trying to make her way home, to swim across the North Sea, back to Wales.

None of this is a reflection of the person she was in life—by all accounts intelligent and beautiful and loved by many. It is more accurate to say that these photographs have more to do with my coming to terms with that past. This is an abstraction, a vehicle for working through something so impossibly painful and real, yet now so far-off and intangible, that the passage of time is making increasingly difficult to grasp. It felt as urgent to make this work then, as it does to move on with life now.

https://www.skinnerboox.com/books/theunforgetting

www.theravestijngallery.com