The role of a gallerist is to comprehend the contemporary historical moment, to develop a flexibility for absorbing changes, to create a distinctive viewpoint and to find artists with an innovative language that can communicate that. My own comprehension of the present is inextricably connected to the past, and that has and forever will dictate the way I work.

I am originally from Tehran and I moved to Milan in the 1960s; I instantly loved the city. Its eclectic environment fed my spirit and desire for curiosity and freedom. After experiencing the stiff environment of the Jewish School in Milan, I had an anti-reaction to that atmosphere and embraced my rebellious spirit by joining the feminist movement in the 1970s. I now recognise that rebellious side as a common theme throughout my life—I’ve always felt the need to conquer my own independence and affirm my unique persona as well as the curiosity to discover more of myself.

I guess that is also why I started building a business at a very young age. My father was a carpet dealer and I owe my passion to him but our tastes didn’t really match. Perhaps it was the generational gap, but we both knew that we’d be more successful as two separate businesses and so he helped open my first gallery in Via Bigli in Milan. It was 1979. At first I was dealing antique and nineteenth-century French carpets but during a trip to New York I was astounded, completely by chance, by a Swedish carpet. It was so different, so alien to everything I was used to. So of course I went to Sweden and purchased a great deal of carpets and furniture that I just liked: to be completely honest I was totally ignorant in the field of design so I didn’t really know what I was doing but my instinct guided my decisions. That hasn’t changed. That trip was paramount to my career: I purchased important pieces from Alvar Aalto, Hans Wegner, Bruno Mathsson, and many others. And I never lost that natural trust in my intuition; I have continued to look for pieces that I genuinely like and that will distinguish Nilufar from anything else on the market. I believe that remaining true to my own vibrations, in a not entirely conscious way, is what allows me to take risks.

I am not one to forget the past; on the contrary, it is a cardinal element for progression. But I don’t forget the present and future either, which is why I am on a perpetual hunt to find new creatives. My talent scouting career, if we want to call it that, started with Martino Gamper. He demonstrated a great desire for experimentation which is something that always elicits a positive reaction in me. So we started working on If Gio Only Knew, a performance organised for Miami Art Basel, where Martino reworked Ponti designs that had originally been for the Principe di Savoia hotel in Sorrento. That is the perfect example of how I see the delineation of the future: profound respect for and in-depth knowledge of the past blended with a rebellious and unapologetic contemporary approach. There is no future without the past and it is essential for contemporary artists to challenge it. The reactions I expected were: “How dare he? How can he even think of touching Ponti’s designs?” But I actually believe it to be an homage to the master; to truly admire someone and make them part of your journey you need to touch them, you cannot fear confrontation. Play with them instead. Gamper’s idea was absolutely shocking but a tremendous success. The Ponti family sent Nanda Vigo to have a look at Gamper’s pieces and we were all very happy to hear her response: “This Martino did a great job. He really interpreted Gio Ponti.” Martino is such an important artist in the gallery’s story and our bond continues, we will be staging another important exhibition of his work for the Salone 2022.

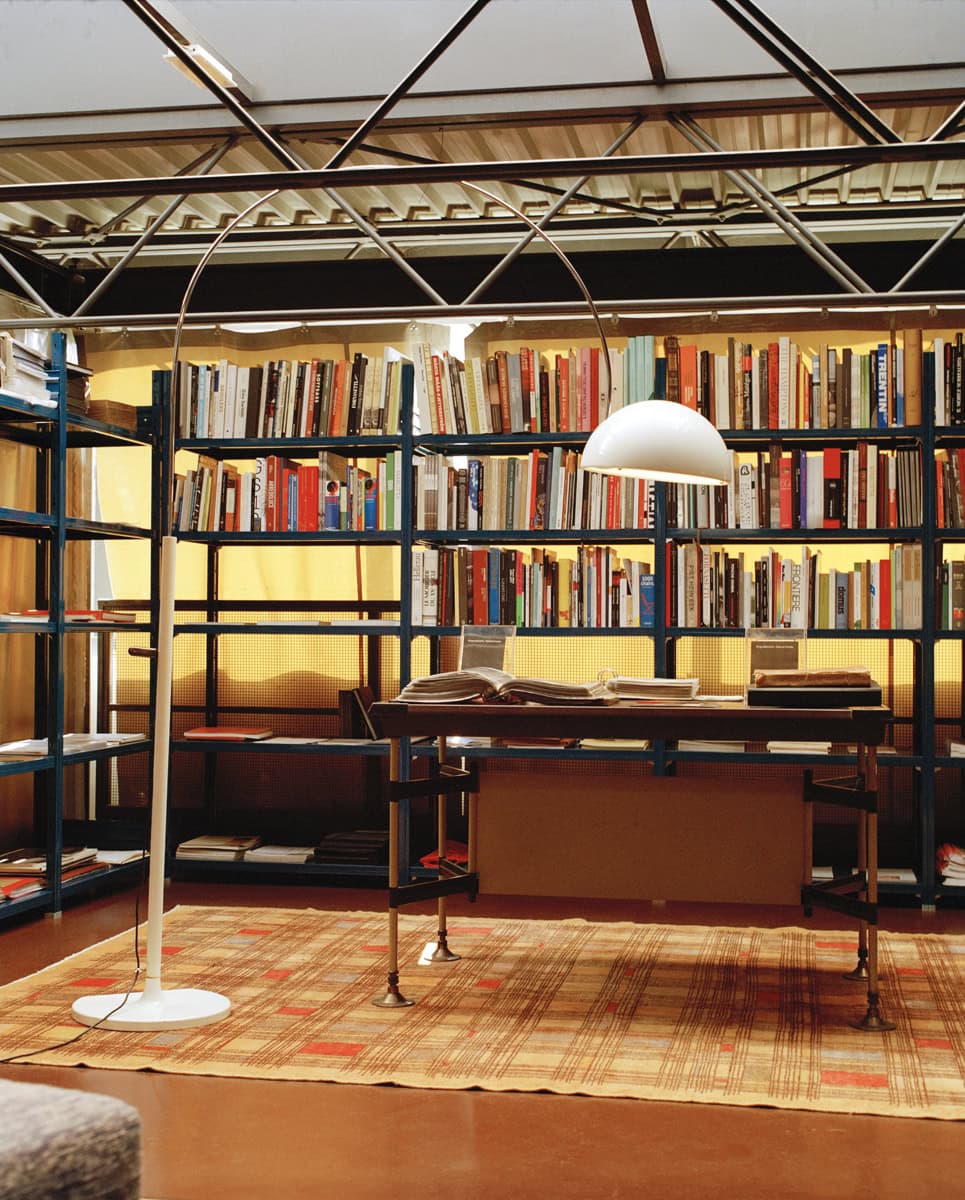

I am constantly curious not only to discover new talents but most importantly to discover the public’s reaction; it is only then that you truly understand the potential of a piece. I want to surprise and excite, otherwise I don’t really think I am doing my job. The way I understand it, my job is to tell stories: people don’t buy pieces because they want to own the object but because they want to fall in love and be part of a story, a meaning, a feeling. It’s my job to provide that story as best I can. The objects at Nilufar are testimonials to history and genius hands and minds; they encapsulate curiosities, moments and relationships. It is important and beautiful to remember but also to envision, and it is a special moment when an object allows you to do so. This was the origin of the Depot, a place where we could gather these avant-garde and futuristic stories, whether older or contemporary. I created the Depot to be a living museum where I blend historical and contemporary pieces. It is a 1,500-square-foot space that, regardless of its size, still feels so comforting and familiar to me. I think the best part was filling it with a crazy number of objects: someone once said they counted 415 pieces. I opened the space in 2015 to the disbelief of many. It was a big change from the gallery in Via della Spiga to a warehouse, formerly the city’s silverware factory, outside the centre. But it was this unconventional aesthetic that drew me in. I could just imagine the balanced clash of the multitude of designs that define my story, unexpected but so naturally Nilufar. I didn’t just want an exhibition space, I wanted a space where things would happen: meetings, gatherings, exhibitions, performances, fashion shows, book launches. I wanted a space that would feed and reflect my eclectic personality. I wanted to make things happen in a place that narrates the history of design while at the same time predicting its future.

I also liked that it was so close to the Politecnico because I wanted to create a bridge between generations and add my own contribution to their education. The past is our direction, telling us where the market will go; older objects hold a unique value due to their “emotional baggage”. Rarities will continue to acquire more interest as exemplary of an era, a movement or an artist and that historical connotation is fundamental for enthusiasts. In our new and developing sustainable mindset, we are also more prone to giving new life to antique objects, so discovering and appreciating them is part of the process. All of this makes me happy because I don’t comprehend the concept of “getting tired of something”. How does that happen? How do you get tired of beauty? No, you don’t get tired, you just start thinking about them differently. Less like design and more like works of art.

But really, what I’ve come to learn with time about my approach is that I strive for synergy between old and new. Thinking about the Lina Bo Bardi exhibition we hosted, I went to visit her Casa de Vidro in Brazil beforehand: my first reaction was fascination with the rationalist architecture in juxtaposition to the natural wealth of the forest. The second reaction was excitement as I walked in the door and witnessed a unique, utterly random and non-hier-archical mix of antique interiors, modern art, pieces designed by Lina herself, folkloristic collectibles and books which, all together, gave form to the concept of timelessness. That strongly resonated with me. The dialogue between things, people, times, styles, opposites is always a favourable generator of special happenings. As I was saying for the Depot, I am trying to create a harmonious cross-temporal and cross-cultural synergy between “things” that you wouldn’t imagine together. Because this is the direction I see our culture heading towards. My work is not based around objects but around environments, atmospheres, stories — and there are hardly any “one way” stories anymore.

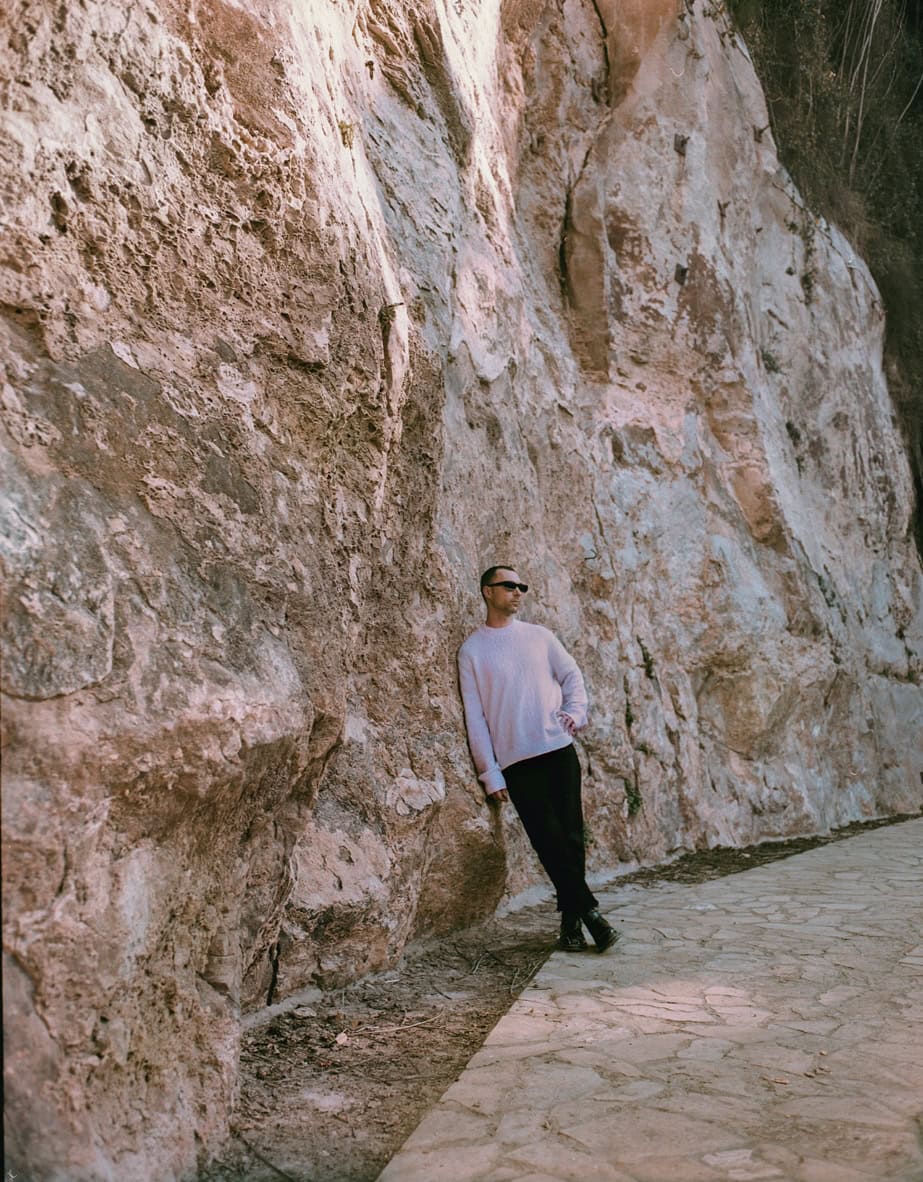

Take Andrés Reisinger, another unconventional choice for the gallery. We started working together for Milan Design Week in 2021 because I wanted, as always, to take us to the next step. Andrés is an incredible artist who has the ability to interpret the hybrid quality of our time, with the digital realm slowly but steadily conquering so much of our physical space, with an innovative and incredibly appealing and comforting aesthetic. And Andrés does not design objects or interiors; he designs atmospheres and environments that are at the middle point between physical and digital. We’re working together again for Milan Design Week 2022, of course.

I am excited about the energy I am witnessing in Milan, in design, in art, and everywhere else. The desire to regain control over our lives and engage with a new quality is permeating the air.

I am often asked whether I think the digital realm will substitute the physical one or asked to discuss the two separately, as though they were too different to ever coexist. I disagree. I focus my work on building a bridge, on developing a new system that enhances our experiences in both. I am also often asked about the metaverse with such curiosity, surprise and doubt. This is all important, but sometimes we fail to recognise how much of our life is already entangled with the digital sphere, how much our behaviour is dependent on and influenced by our experiences in the digital dimension.

I don’t want the metaverse and the digital realm to be understood as a threat; on the contrary, they are portals to an infinite number of beneficial possibilities. My practice is focused on expanding the prospects of the digital present and facilitating better acceptance. What I attempt to achieve with my projects is reassurance, a complementary ideal or the reflection of my understanding of the future: a hybrid of dimensions.

I was born and raised in Buenos Aires in the 1990s and creativity has always been my preferred outlet. One of my most vivid memories is observing the difference between me and my peers: my friends wanted to play video games, while I wanted to create the environments within those video games. The opportunity to generate a parallel universe where part of me could live was thrilling and, of course, powerful. It is a practice that requires creativity, understanding, interpretation, research and a whole lot of discipline and methodology; I was trained in classical music and my parents are scientists, so I guess that approach is rooted within my personality.

Because of my methodological approach, understanding all facets of a process is crucial to what I personally consider a successful project. That includes examining my own creative process but also how it positions itself in a wider cultural context. In that sense, some of my greatest sources of inspiration are historical characters: their lives, journeys and accomplishments and how they have shaped our culture into what it is today. I need, and I believe we all do, to really comprehend what has been done before in order to formulate the future. I am the result of something and to develop my vision I need to fully grasp how that something came to be and its reason for existing. Digital artists are not breaking from the past, on the contrary. I always ask myself what has already been done in the digital realm and what more can be done? How can the digital implement positive change? How do we build peaceful worlds? That is how my work begins, a process of experimentation and failure. It’s a journey built on the tension that lies in alternating moments of joy and suffering. The freedom to create, ideally, whatever you desire comes with great responsibility. The outcome needs to be a moment of peace and that is not always easy to find; the suffering comes from the perpetual state of exploration, trial and error that precedes that apex state of tranquillity. That is why many have defined my work as surreal and dreamlike—because it represents that state of bliss.

And that state of bliss should not be thought of as being confined to a digital realm; let’s just say that in the physical world it acquires a different definition. It is a feeling of accomplishment thanks to positive outputs. To illustrate this, I am going to briefly talk about something that, to this day, I consider one of my biggest accomplishments. Back in 2020, I created Hortensia, a digital design that, as always, I shared on social media. It instantly garnered huge interest and popularity, to the point where I started receiving orders for it as a physical object, even though it didn’t exist and I had never presented it as such. I blame that on the power of 3D to create incredibly realistic forms. When developing the digital Hortensia, I didn’t plan for it to ever be physically produced and because of that, its design was incredibly complex. But after much consideration, Júlia Esqué and I decided to produce it as part of a limited collection of physical objects that sold out very quickly and because this physical counterpart continued to enjoy so much success, we teamed up with Dutch design brand Moooi to produce it in larger quantities. This to say that creating demand before supply is possible and, of course, a total disruption of the system. Usually you would launch a product and hope for a positive response from the market; we turned that process upside down.

I was so pleasantly surprised and proud of this achievement. Just consider the significance in terms of sustainability. With the kind of constant interaction we have with the public, we can gather information on the actual cravings and demands of the market and put a design into production only when we have something that truthfully embodies those cravings and demands. That experimentation I was talking about earlier is key in this mechanism; with digital design, you can allow yourself to make as many mistakes as necessary without fearing the physical implications and ensure you are only making objects that people actually want. Then just think of extending that same concept to something greater than furniture, such as living spaces, buildings, cities. It sounds futuristic but it’s really not so far off. I also truly believe that if we learn how to effectively transfer some of our daily physical tasks to the metaverse, which allows for easier implementation, we’ll find that we have more time to dedicate to our physical spaces and in turn improve our relationships with them. There is so much the digital realm can teach us about our physical sphere. Take my example, I didn’t think Hortensia could be physically produced, and yet I learned that the possibilities of artisanship will never cease to amaze me, far exceeding the general idea of what we think we are able to produce.

Scenarios like these are also the reason that I have accepted that clearly conveying what digital design really means is also an urgent aspect of my job. That physical/digital hybrid, as I like to call it, is to me the only way forward to an improved future. The digital realm is not a cloud that will engulf everything human; it shouldn’t be understood as a choice—an aut aut—but as a complement. Owning an artwork in the digital realm doesn’t mean that you won’t still appreciate the physical experience, the same way that meeting your friends in the metaverse won’t replace a physical gathering. We need to start thinking less about “instead of” and more “together with”.

That is why my work is a combination of digital and physical elements and why I often play with confusing the two. I like to provoke viewers by creating artworks that hold an uncanny aesthetic, one that looks realistic but slightly odd and deformed, one that disorients and unsettles: is this digital or is it physical? Is it a render or a photograph? I want to touch it, but will I ever be able to? I want to raise questions as this is really one of very few ways to grab people’s attention and not be instantly dismissed nowadays. My question could easily be translated into this concept: if you’re finding it difficult to tell the difference, what difference does it actually make? Is an experience less real if we experience it through a screen? And is the digital not real? When someone like Nina Yashar, an essential catalyst in the shaping of design, trusts your vision, you know you are moving in the right direction. The Nilufar exhibition Odyssey was an example of the hybrid I so eagerly believe in.

Many of our ways of life and our relationships with objects are a result of social codes rather than logical functionality. The kitchen is not just the space we cook in but the heart of the house where everyone gathers. We should be brave and trust ourselves when it comes to learning new social codes: it’s an exciting possibility rather than a threat. In the metaverse, we won’t have some of the needs that we currently have in the physical world; in the simplest terms, we won’t need a ceiling and walls to protect us. But in the design process, I cannot ignore what makes us human and that is comfortable living that goes beyond functionality, so that’s why I include these elements in my projects. It’s a slow process of expansion with many challenges and I am thankful for the people who are taking part in this evolution, like Nina. She has an impressive visionary talent and it is crucial to have such great minds on your side.

There are so many more questions I want to provoke and so many more questions to ask myself. And that’s yet another lesson: I never want to stop asking, wondering and playing with things.