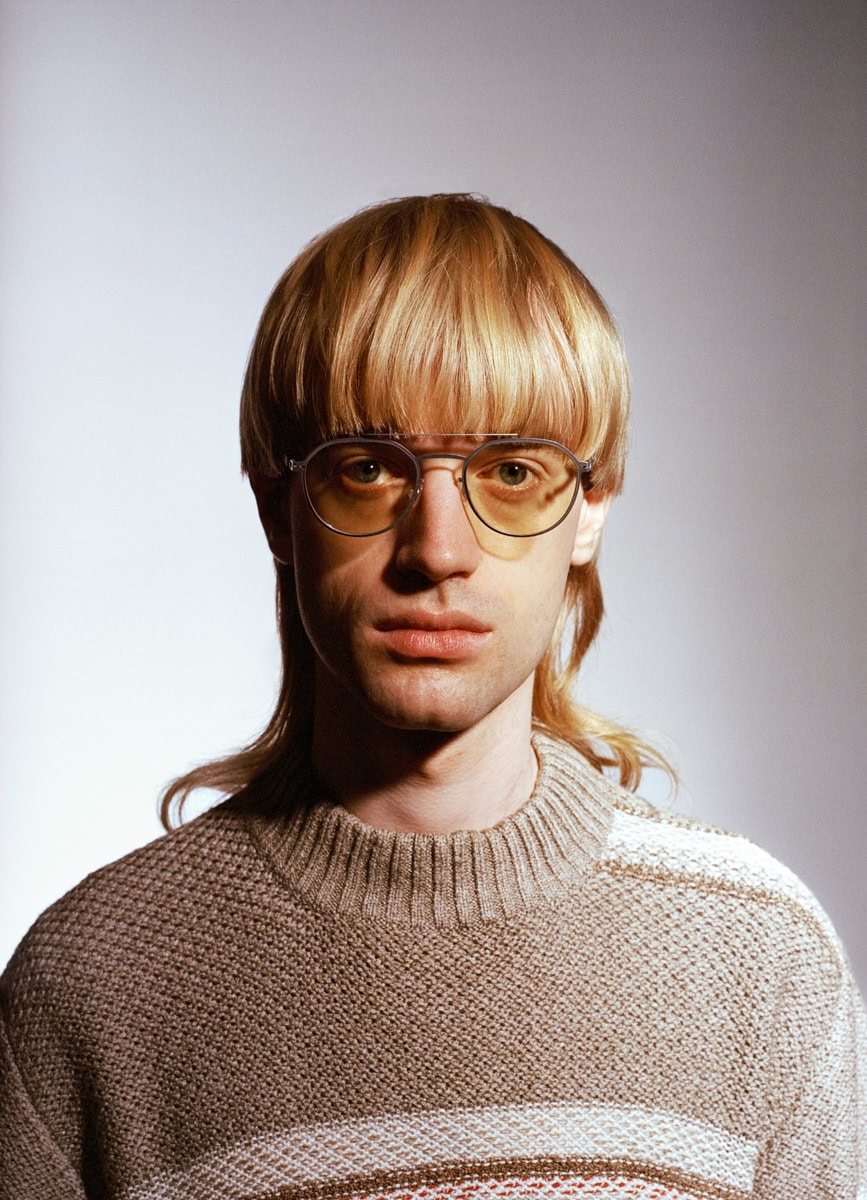

Joe Exotic, one of the most memorable Netflix characters in recent years, gazes into the mirror in his grotty bathroom, caresses his locks and states: “Gotta get the curls out, they’re my sex appeal.” Questionable but totally in keeping with Oklahoma beauty standards, or should that be non-beauty standards? Nonetheless, there must be a grain of truth in it because google hits for “mullet” went up by 124% when Tiger King was released, as did searches for animal print.

The mullet has played a role in the appeal of other TV characters in recent years too, from Money Heist to Don’t Look Up via Stranger Things. And you don’t need to be an Oklahoma redneck to love the look, one of the main reasons is the return of ‘70s and ’80s aesthetics, the era when the mullet was the big thing, seen on David Bowie, Paul McCartney, Cher, Jane Fonda, George Michael and other icons.

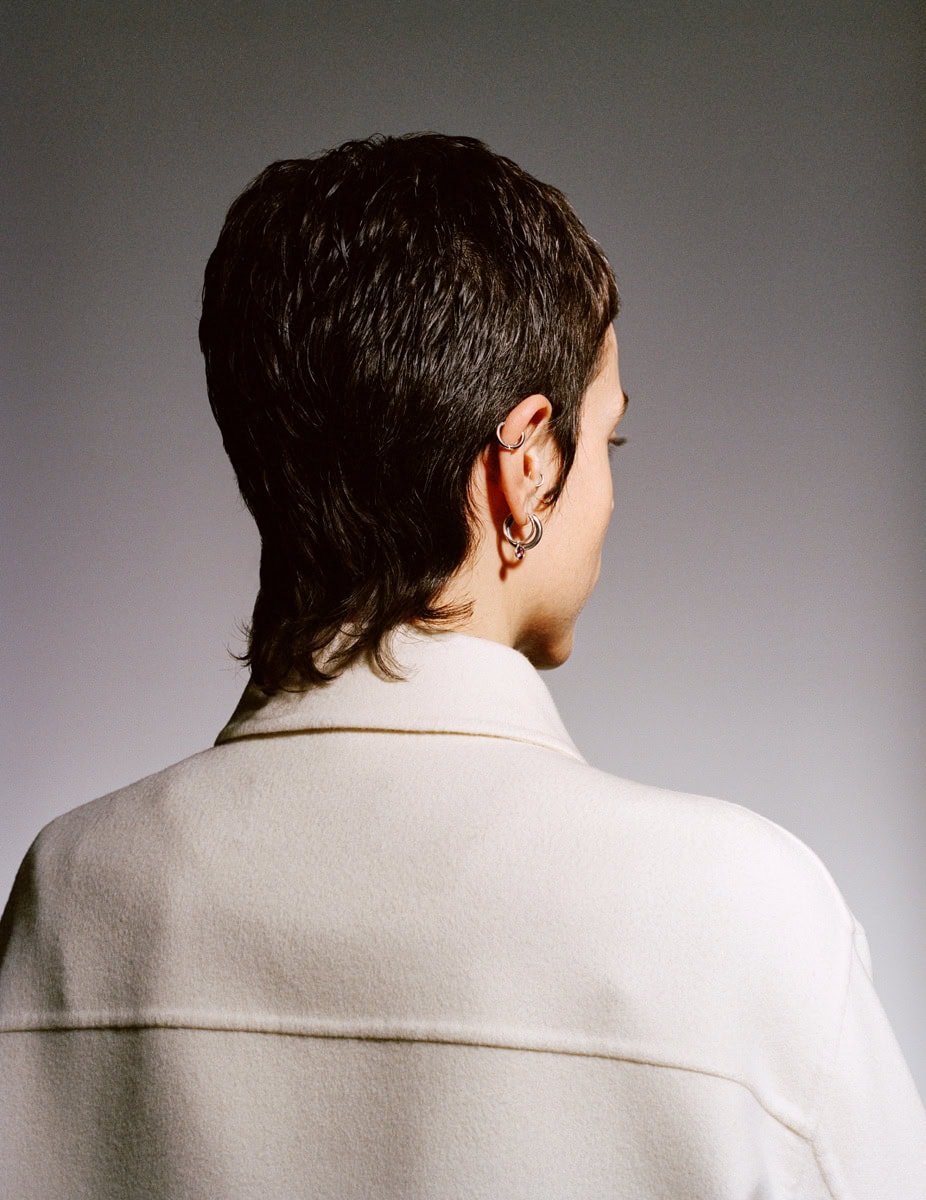

The success of those years is reflected in the new TikTok aesthetic, the effects of the pandemic and our new habit of checking ourselves out in the webcam during endless boring Zooms, revealing unruly hair curling round the backs of our necks, perfectly matching the pyjama bottoms we couldn’t be bothered to change. The Beastie Boys (perhaps) coined the term in the ‘90s, Homer had already associated the style with the rough crowd in the 6th century BC and Benjamin Franklin sported one for diplomatic talks with France. While it was bound to make it to the catwalk in one fashionised way or another, the mullet has never lost its powerful aggressive and counterculture character, even when it broke into online culture, which is why it continues to elude labels and boundaries. Suzy Ronson was hairstylist to David Bowie in 1972 when he presented her with a photo of a campaign by Kansai Yamamoto. The model’s hair was red and spiky with a short fringe and long at the back. Ronson recalls that at first she thought it was a weird and difficult cut, neither for men nor women, making it perfect for the character of Ziggy Stardust. With Bowie, the status of the mullet grew and grew. The lesbian community adopted it as predecessor to the shag and queer emblem and from there, punks, skinheads and weirdos introduced it into their look. The mullet has preserved its androgyny over the years, now accentuated by the increasingly common representation of a new masculinity or neofeminism, the spirit of an age obsessed with defining time yet with a tic that keeps looking to the past. There is more than one reason to explain why the mullet is the haircut that best reflects the zeitgeist, influenced by the content we scroll through and Gen Z’s new need to seek the cultural horizons of their lifetime on other pages of the dictionary.

The months spent at home during the first lockdown were a time in which we all enjoyed not having to justify our laziness. As the days passed, even the most loyal buzzcut devotee saw their hair grow wildly, from weekly fade to unruly mess. Of course, our constant presence in front of an ever-on webcam, especially if it was for work, meant maintaining a minimum of decorum or even just a decent silhouette. We all got used to seeing ourselves more dishevelled than usual during the pandemic and it was a time of enforced patience when many decided to grow out their hair, with the mullet proving the coolest choice, other than geometric fringes that would defy any set square. The mullet revealed itself to be an ideal cut for the webcam: it develops upwards instead of outwards, making it ideal for portrait mode, which is what we have all been using for the past two years. This meant the mullet fitted in perfectly with TikTok effects and aesthetics and suited its youngest creators, with their fluid style and language. Not to mention that cult of impromptu beauty represented by suggestive gazes in cars and long unbrushed hair, in which the sloppy effect is, naturally, entirely calculated. This TikTok aesthetic owes a lot to 1980s America, not surprisingly the decade in which the mullet was the must-have celebrity trend. Think sex icon Patrick Swayze and his mullet in Dirty Dancing, a film where the dancing wasn’t all that great but positively exuded passive eroticism, ideal for TikTok had it only been shot in portrait. Despite the domination of portrait shots in the media content with most influence over trends, films and TV shows continue to guide our purchases and the return of the mullet may have its roots in some recent Netflix productions.

Among the Netflix phenomena are Úrsula Corberò’s mullet in her role as Tokyo in Money Heist, an androgynous and distinctive personality, in part thanks to her hairstyle. Then we’ve got Steve and Billy from Stranger Things, a series that faithfully reproduced every single detail of ‘80s style, mullet included. In Don’t Look Up, Jennifer Lawrence is a nerd who doesn’t care about her appearance—here the choice of mullet is about convenience rather than style—who meets the stray and scruffy (but sweet and besotted) Timothée Chalamet, kitted out with a mullet of his own in turn. Joe Exotic’s mullet is first stylish then convenient, at least according to the Tiger King himself, aka a character that no Netflix screenwriter could ever have imagined if he didn’t already exist. In no particular order: tiger tamer, conman, candidate for governor of Oklahoma and president of the United States, and gay, polyamorous, vengeful cowboy with homicidal tendencies. Even with all that, Joe needed a stylistic trademark to ensure he stood out from the crowd, hence the bleached mullet beneath the hat. And even the Netflix marketing department got wise to the power of that two-tone mane, collaborating with street barbers in New York and Los Angeles to offer free mullets to customers for the release of the second season. None of the abovementioned characters is simply good. None of them are simple or balanced, never bland. They are antiheroes who combine aggression and good intentions, like all the best plots. More than any other trend of recent years, it is the mullet that has united most different realms, despite their apparent contradictions, spotted both on the Paris catwalks and boorish collectors of exotic animals. The “Kentucky Waterfall” or “Mississippi Top Hat” (other names for the mullet in the USA), as well as being the queer style per excellence, belongs to no precise social class. It is the cut of both radical subcultures and the bad boys of private schools and the Ivy League, tickled by the thought of rebellion, today as in ancient times. In the Illiad, Homer described the Abanti population and “their forelocks cropped, hair grown long at the back”. The style worn by togates and thugs alike.

Despite having traversed multiple ages separated by hundreds of years, the modern origin of its name only dates back to 1994 and the track Mullet Head by the Beastie Boys, terminology that was included in the Oxford English Dictionary a year later. It may be a coincidence, but the urgency to define this style came about in the ‘90s, the decade in which the mullet became part of an ironic starter pack, stereotypical of the obtuse redneck. The style was seen as ridiculous, worn by freaks, similar then to its contemporary reinterpretation, the basis for plenty of memes and caricatures. Among the few ‘90s examples that have stood the test of time is Tummler, the character played by Harmony Korine in Gummo, although in common parlance the cut has become synonymous with people who aren’t particularly bright. This fluctuating opinion of the cut has been a leitmotif of its long history yet let us not forget that years before it played a role in the founding of the United States of America.

In 1700, Benjamin Franklin specifically chose our shabby and humble hairstyle, short at the front and long at the back, deciding to go without face powder, wig and opulent clothes, in order to convince the French governor to increase financial and diplomatic support for America. Franklin wanted to make an impression on the French ruling class by personifying a man freshly arrived from the new world. And this isn’t the only time that the mullet has played a political and diplomatic role. In America once again, this time back in the year 800, the Native American Chief Joseph and his Nez Perce tribe resisted pressure from missionaries, who imposed a short and civilised haircut. Their haircut—a combination of mullet and mohawk—was of great spiritual significance for the tribe and it quickly became political. Negative bias towards the mullet must have worried the Iranian governor too, who banned it in order to “stop the spread of the Western invasion” in 2010, seeing it as a symbol of cultural rebellion. A similar event occurred in Perth, Australia, where a school banned the style on the grounds that it was “extreme”. Millennials and Gen Z have used these extremisms in recent years in order to understand their own time which is increasingly engaged in mini revolutions to define concepts of individual and collective identity. Given the current artistic fervour, disinhibition and focus on themes including beauty and representation, it is no coincidence that the era in which we live looks back to the time when the mullet was at its peak, namely the ‘70s and ‘80s. “Business in the front, party in the back” is probably the definition that best describes the mullet’s characteristics. It reflects the generation that no longer wants to choose between parties and business. A generation that has no interest in the one definition but wants to be seen from the front, back and sides, all at the same time.