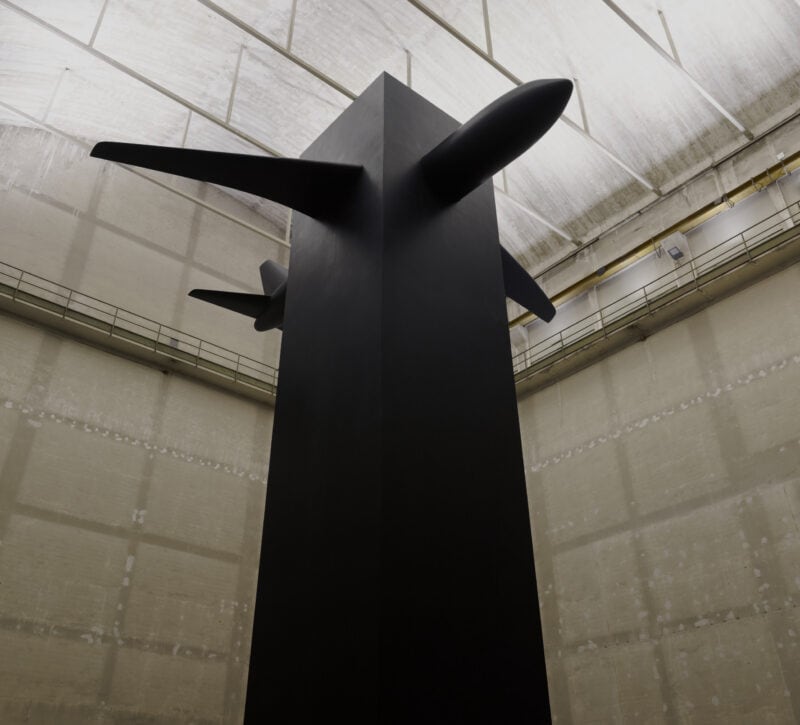

If it were not for Maurizio Cattelan, the most ironic and provocative artist in the contemporary art system, the work Blind (2021), in opaque black resin, composed of a monolith and the silhouette of an aeroplane intersecting it, might be considered a majestic memorial to the attack of 11 September 2001. But the artist has not solely appropriated an image both dramatic and powerful, which has become part of the collective iconographic repertoire (the plane crashing into of the Twin Towers), to transform it into a work/symbol of pain and its social dimension. Blind seems to contain a terrible enigma, bringing together multiple issues and frictions. It seems like more than just a memorial with a destabilising iconography, more than a continuation of the series of reflections on history and death that the artist began with the works Untitled (1994), Lullaby (1994) and Now (2004), referring respectively to the kidnapping and execution of Aldo Moro in 1978, the Mafia-style attack on Milan’s PAC in 1993, and the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas in 1963, and with All (2007), a marble sculpture representing the silhouettes of nine anonymous corpses covered with a sheet. The monumental work exhibited at Hangar Bicocca further expands on the previously explored themes of pain and death, and further extends his terrible and as yet unresolved questioning. In a recent conversation, the Paduan artist explained: “I’d had this work in mind for several years, but the pandemic has made death visible again in our lives: we always try to remove it and forget about it. We are all projected towards our own wellbeing and away from any kind of pain, as though it were a purely medical problem, but perhaps for the first time since our parents’ generation lived through the war, death has once again become an everyday spectre. […] I was in New York, boarding a flight, on the day of the Twin Towers attack. I had to walk home from La Guardia Airport. It took me hours and what I saw has stayed with me. They were terrible, apocalyptic scenes, and I still carry with me the memory of that tragic event, which revealed all the fragility of our human condition. […] Certain images and objects have incredible symbolic power, they are so strong that they take on a wider meaning and become evocative of many things, not only of that event. In this sense, taking a certain spatial and temporal distance becomes a necessary step in remembering.”

But the title Blind also seems to function as a key to unlocking other, more subtle and obscure questions. To whom or to what does the title refer? Is the viewer blind if they cannot see and understand the message hidden in the totemic structure, which fuses the destroyed and the destroyer together forever? The aeroplane recalls the shape of a crucifix and the black monolith seems to evoke the Kaʿba, Islam’s holiest building, although its dimensions are deliberately more dilated in its vertical stretch, as if it were two images laid over each other: a blind, windowless skyscraper made entirely of stone from meteorites fallen from the sky. Does Blind incorporate the symbols of the two monotheistic religions that worship the same God but have been fighting for centuries? The Kaʿba (or al-Kaʿba; Arabic: كَعْبَة , kaʿba, derived from the noun kaʿb, ‘nut’ or ‘cube’), an ancient building located inside the Holy Mosque in the centre of Mecca (in Saudi Arabia), is the holiest building in Islam, and identified as the first temple dedicated to monotheistic worship, sent down from Paradise by God himself. It is covered with a kiswa, a precious black silk veil, richly woven with gold and silver leaf bearing Koranic inscriptions. In the eastern corner of the Kaʿba is the Black Stone, a black mineral block most likely from a meteorite. It is approximately one and a half metres above the ground. The Kaʿba is also called the ‘black box’ because of the colour of the kiswa that normally covers it. According to Muslim tradition, the entire area surrounding the building (matāf) was a burial place for the very large number of prophets who preceded Muhammad.

With these references and memories that draw on millions of lives lived in the past, it seems to me that Cattelan’s monumental work goes even further than what he wanted to evoke with The Ninth Hour (1999), the famous and highly disputed image of Pope John Paul II being crushed by a meteorite. At the time, Cattelan was less daring and he chose the figure of the Catholic pope, a stunt that went after an easy target and an action that obviously enjoyed a lot of success and visibility in the contemporary art system and in the media. Quite another provocation would have been the choice of putting the meteorite on the body of the greatest exponent of the Islamic religion in the nineties, the Imam of that historical period, or even of Ruhollah Khomeyni, who in the seventies and eighties had been the Supreme Guide of Iran, and who caused many problems to those who dared to criticize fundamentalism and certain religious issues of the Islamic world. But now, in 2021, Cattelan and curators have chosen to place the black sculptural block – the Moloch of 9/11 – in the large “Cubo” room (after the shape of the space) at Hangar Bicocca. The enormous black sculpture, which merges symbols of two apparently opposing cultures – Western with Eastern, Christianity (which has approximately 2.3 billion believers, corresponding to 31% of the world’s population) with Islam (which has about 1.8 billion believers, or 23% of the world’s population), history with current affairs, colonialism with rebellion, etc. –, is enclosed in the Hangar Bicocca’s bright cell, as though the relationship between blackness and brightness should inevitably trigger a short circuit or a spark or a hypostasis full of questions. The black monolithic presence is at once fearsome and fascinating, exuding the allure of a form and a polysemy of contrasting meanings, a terrible perfection that has visually solidified in the collective consciousness. The black totemic sculpture translates a mixture of fear and attraction into form. Horror and fascination dwell in Blind, where antagonistic forces continue to move primitive impulses for power and knowledge, as in the black monolith that came from the universe and fell into the story imagined by Stanley Kubrick in 2001. A Space Odyssey (1968).

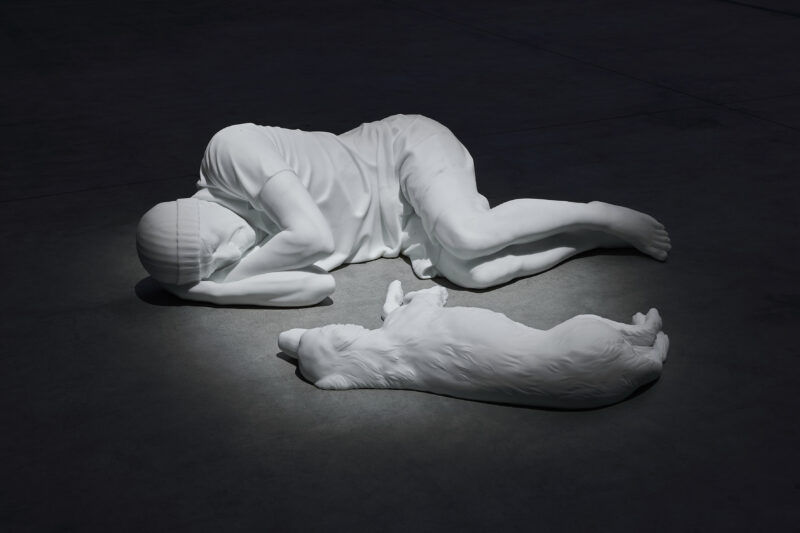

Returning to the memorial sculpture placed in the cubic cell of Hangar Bicocca, years ago Boltanski had already identified the possible relationship of the work in a symbolic-sacral sense in its relationship with this space, pervaded by an atmosphere similar to somewhere in which something of blind fate was condensed. During the preview, Cattelan invited us to reflect “on art that deals with creation, life and death, basically the same themes from the beginning of human history. […] These themes are intertwined with the ambition of every artist to become immortal through their work. […] Every artist is confronted with both sides of the coin: with a sense of omnipotence and with failure.” The destruction of the World Trade Center was not only an attack but an event comparable to something whose reception invades the field of ritual, in its most bloody and ancestral meaning, like a ritual performance with planetary impact. And it must be brought back into the sacred to be understood and processed. In 2001, Karlheinz Stockhausen provocatively defined the attack on the Twin Towers as “a cosmic masterpiece”, “the greatest possible work of art in the entire cosmos”, “Luzifer’s masterpiece”, which sparked indignation thanks also to media use of certain passages of his speech in a way that would further shock viewers and create an audience. Has Cattelan translated what the great German composer intended to say into a sculptural work? In other words, that the 9/11 attack was an absurd and majestic operation, the cinematic plot of a disaster film, for which even today we are not sure who wrote the script, a plot that is so meticulous in its details and so perfectly executed, conceived entirely around its visual dimension and conscious of the aesthetic rules of mass society? Has Cattelan translated into plastic form the horror aspect of the sacrificial dimension, the inexplicable and the violence that the sacred brings with it? The numerous taxidermied pigeons arranged in the long nave of the hangar “observe” the visitors who come to the cubic cell in the dark. The artist considers them as mysterious and disquieting “ghosts” – once again, the title of the work, Ghosts (2021), provides the key to the interpretation –, who occupy the same atmosphere and space of curiosity and terror in their thousands. These birds have an incredible sense of direction and can always find their way home if released in an unfamiliar place. But here they are all perched and locked in their positions. In the hangar, their presence is charged with ambiguity. Perhaps they are watching us. We don’t know whether to consider them friend or foe. And we are enveloped in darkness until we see the sculpture Blind, an impenetrable and blind tower, a three-dimensional shadow, a skyscraper that does not touch the clouds but stands silently in cubic space. On the opposite side of the hangar, a human being and a dog –sculpted in white Carrara marble and lit by a spotlight – lie facing each other, huddled together, like very white silhouettes immersed in darkness. Here, too, we rely on the title (Breath) to be sure that, according to the artist, the two subjects are in fact breathing.

Mauro Zanchi is an art critic, curator and essayist. He has directed the temporary museum BACO (Base Arte Contemporanea Odierna), in Bergamo, since 2011. His essays and critical essays have appeared in various publications published by, among others, Giunti, Silvana Editoriale, Electa, Mousse, CURA, Skinnerboox, Moretti & Vitali and Corriere della Sera. He writes for Art and Dossier, Doppiozero and Atpdiary.

Images: Courtesy of Pirelli HangarBicocca

Translation: Victoria Miller