Graphic designer, before completing his education in photography (Ecole des Arts Saint-Luc Liège), Matthieu Litt is mainly interested, in his practice and his approach, in the concept of distance and closeness, the means by which the tracks can be blurred, the markers between images coming from horizons or from radically different contexts. This gave him the opportunity, in just three years, to produce two books highly noticed by the critics and amateurs: Horsehead Nebula (with images from former Soviet republics) and Tidal Horizon, which brews images taken during an artist residency in Norway. Essentially using photography but without exclusivity, he is contributing to a growing number of editorial projects.

His latest book Tidal Horizon brings the photographer to question himself about the dialogue between Man and Nature and to immerse himself in a broader reflection around the notion of the sublime and the way we are disconnected from this notion in our contemporary society.

About ‘Tidal Horizon’ – words by Darren Campion:

If today we are more familiar than ever with the large-scale cycles and processes of the natural world, this is due not only to advances in scientific knowledge but also to the fact that these cycles seem to have been interrupted and destabilized largely through human action. Our awareness of patterns in nature, like those of the seasons and the tides, is ancient, but the way that we have negatively affected those cycles, though disputed in some quarters, is a more recent development, and one that appears increasingly hard to ignore. Matthieu Litt’s “Tidal Horizon” is, in the first instance, a consideration of one particular cyclical process, made obvious by the title of the work, and, in the larger sense, it addresses the human relationship with nature. However, Litt’s approach eschews the documentary in favour of a refined visual and metaphorical vocabulary, giving us new ways to see these cycles, along with new ways to think about what our place in the natural order might ultimately be.

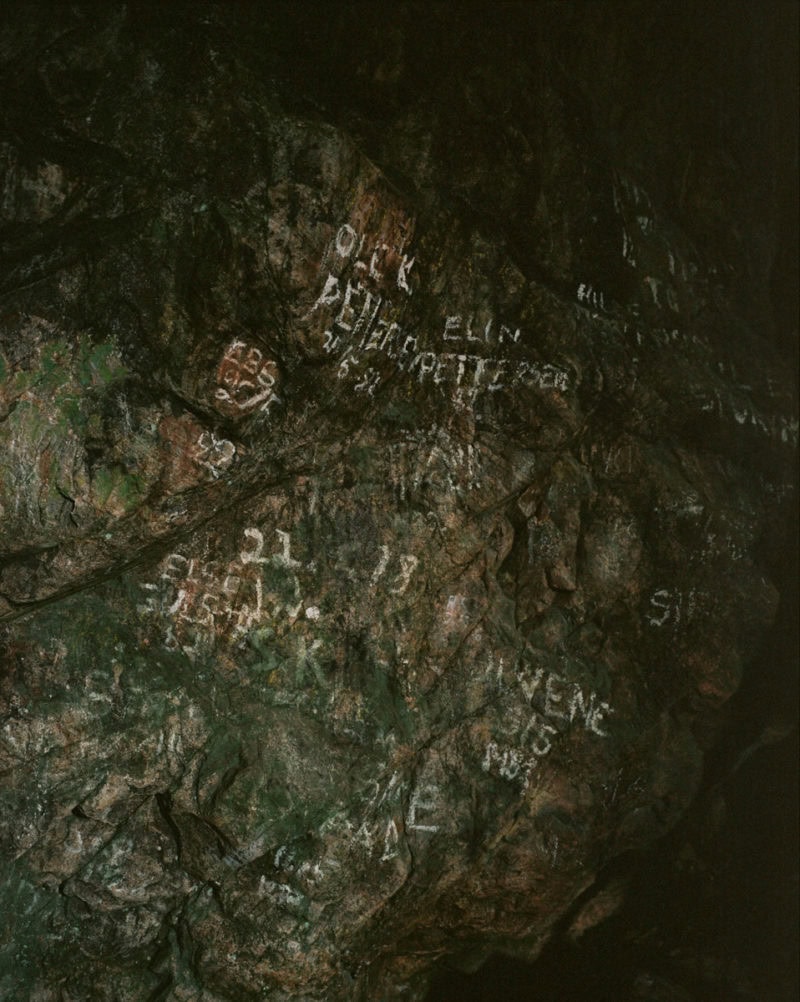

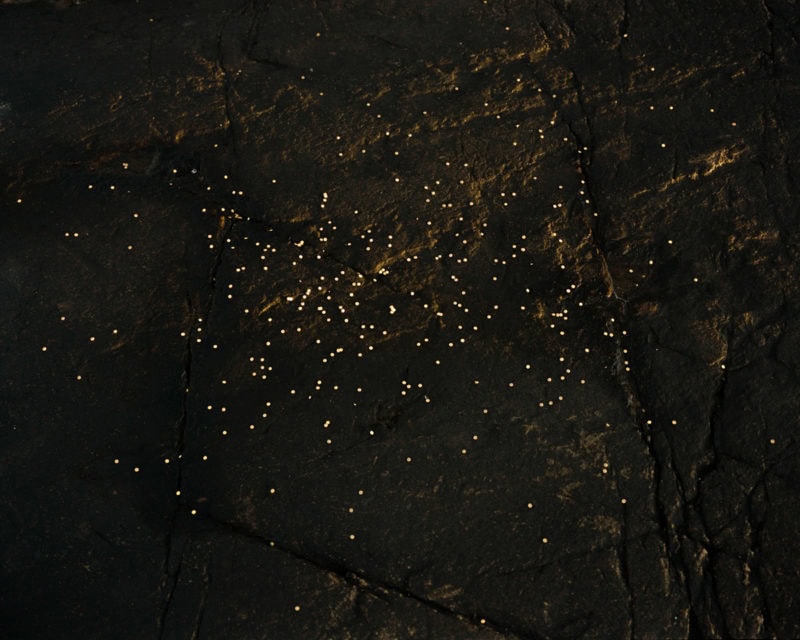

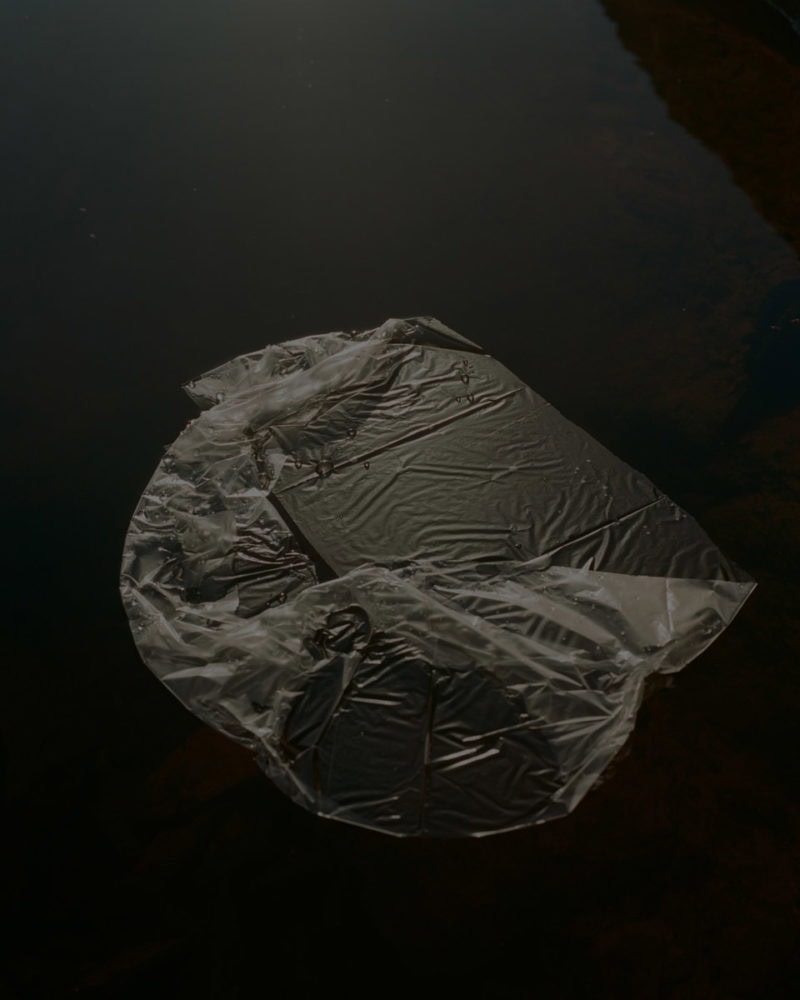

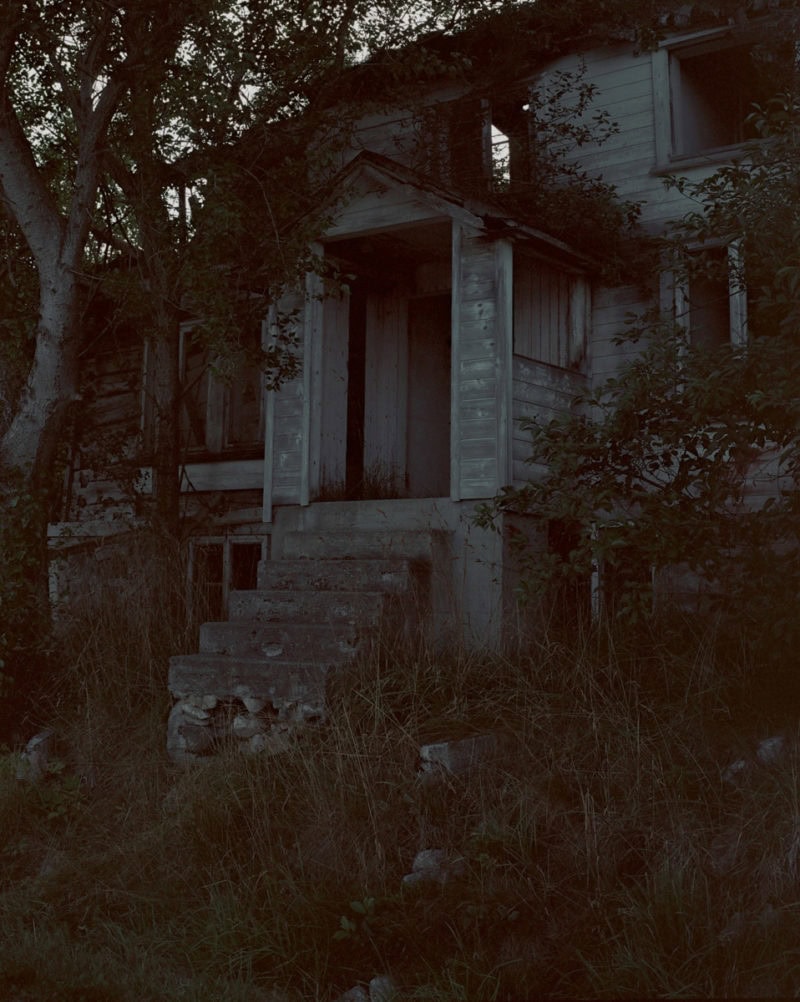

He suggests the circularity of these patterns both in the structure of the book overall, and also in terms of what he has photographed, motifs that evoke reoccurrence and closure. However, they also indicate a kind of disturbance, perhaps calling the stability of these natural patterns into question. Litt’s sense of the natural world is distinctly shadowed; this is not nature generous and bountiful, but something that contains a profound, implacable energy, capable of sweeping away anything in its path. The motion of the tides is, finally, irresistible. Humanity’s place in this order is evoked by one of the opening pictures in the book, showing a group of delicate glass spheres lit by a window and visually echoing the rising sun in the preceding image. Their shape makes us think of the planet as a whole, the sum of those patterns and processes we call nature, and yet the very fragility of this attempt at imitating its basic forms also reveals how insignificant our efforts are bound to be when compared to the vast stretches of time and space on which it operates. Our place in the natural order is simply too precarious to be seen as permanent; the incursions of humanity into the landscape must be continually maintained in order to hold their integrity, and even then it seems to be a loosing battle. At worst we are a destructive force, thoughtlessly set on making the planet uninhabitable, at least for ourselves, because Litt’s tides will no doubt continue without us, along with all the other cycles and processes of which they are a part of. That human constructions are tenuously placed on this forbidding landscape is emphasised in other ways as well. In one strikingly dark-toned image we see what must have once been a fine and well-built house left to decay, a melancholy expression of the fate that seems to be in store for all human endeavor. The way that Litt has structured this picture suggests that the landscape is beginning to overwhelm the house, to reclaim it; nature can, in that sense, thrive on the decay. The man-made is revealed as fallible and transient, while nature itself seems inexhaustible. The eternal reoccurrence of the tides is a fundamental metaphor here, elaborated throughout the work in different ways and operating on different scales, from the minute to the monumental.

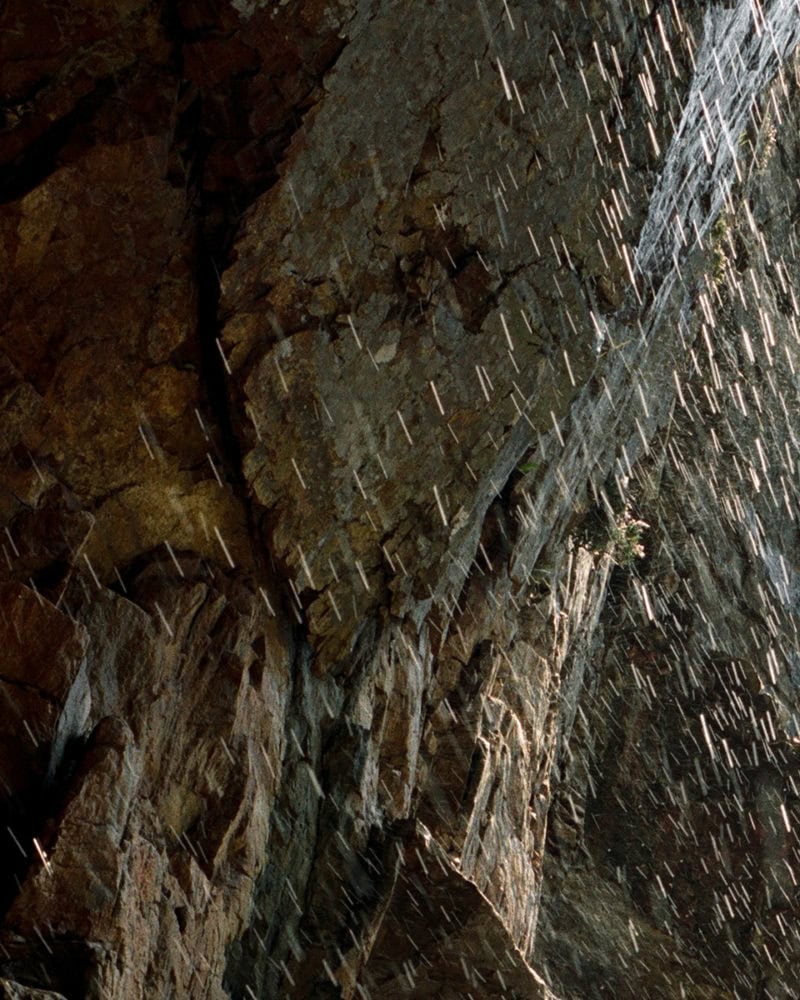

How Litt depicts these processes is often significantly indirect. He spends a lot of time studying the surfaces of water and rock, as well as the places where they meet. This is perhaps because their depths are (literally) impenetrable to a human gaze, but also because these surfaces are where the energy within much larger cycles and processes are manifested. At the same time, he places them in the context of wider, more encompassing views of the landscape, so that we cannot lose sight of the relationship between these seemingly distinct perspectives. What this contrast also underscores is the fact that any human view is bound, in the end, to be a partial one; we can’t fully conceive of, much less control the forces at work here, regardless of whatever damage may have been done by human action. However seductively beautiful in light and form many of Litt’s pictures might be, then, there’s no mistaking the darker undercurrent that moves them; this horizon can also be the point you pass beyond and can’t return from.