Matthew Thorne is an Australian artist whose work is focused around the relationship between people, land, mortality and spirituality.

Recent work includes a documentary series “Positive Movements” shot in Baltimore and Philadelphia (to be released in 2018). Reportage photography series shot in Iran, and Russia. A book of images taken in Japan, “For My Father”, published via Palm* (UK). And a second book of images taken across South America, “Driving Too Long To Be Somewhere To See A Girl”, to be published in 2018.

Commercial work includes additional second unit direction for Alien: Covenant, photography for Huawei with Henry Cavill & Scarlett Johansson, and direction for commercial film work for Lexus, Audi and Qantas. Matthew’s film work has been shown at the Cannes Lions Festival, Young Director Award (Cannes Lions Festival), One Screen Awards (The One Show), LA Music Video Festival, Adfest & Spikes Asia,

And his photography has been exhibited in Melbourne, Sydney and Berlin.

About ‘ The sand that ate the sea‘:

Hi Matthew, please introduce us to The sand that ate the sea.

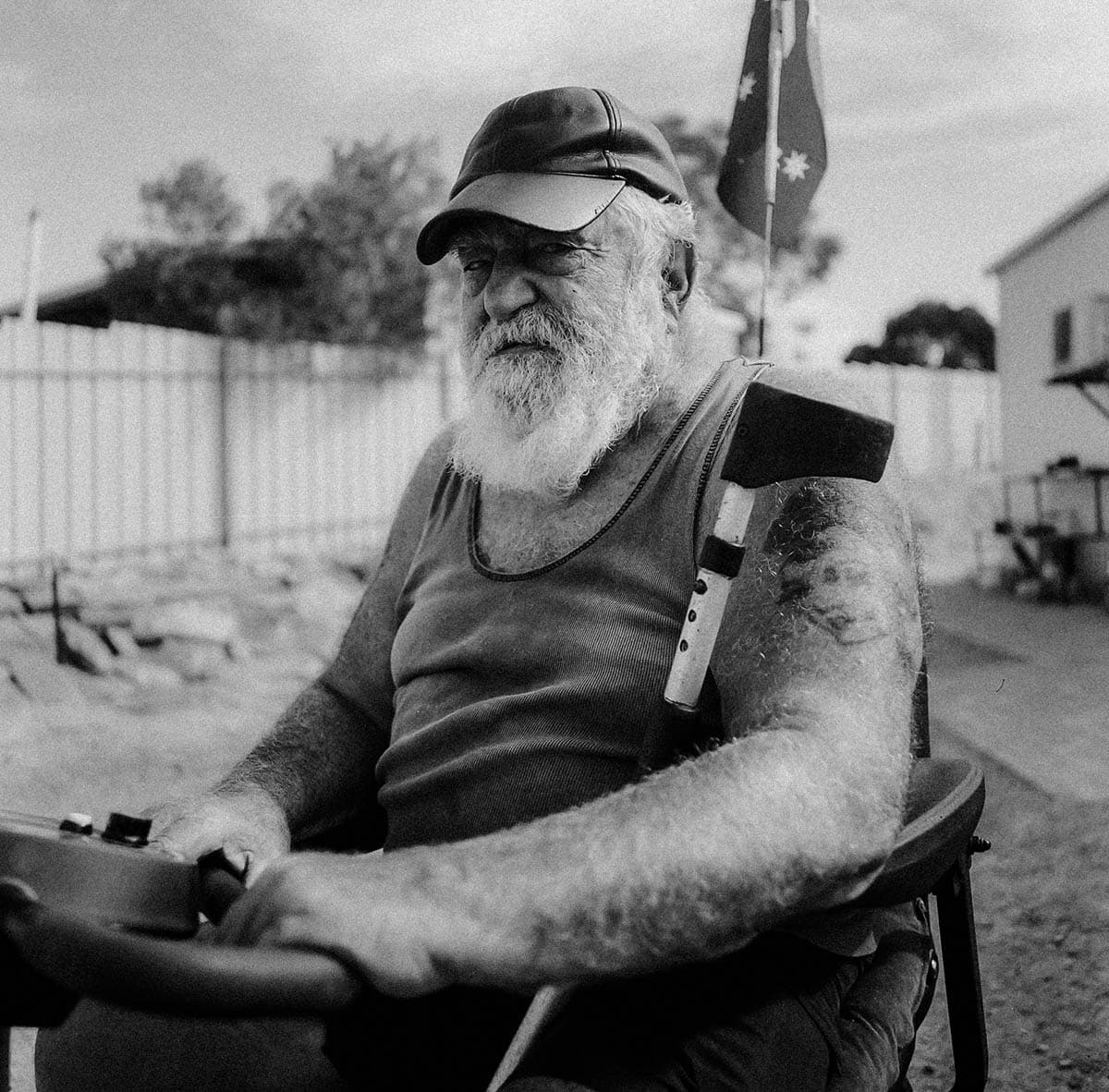

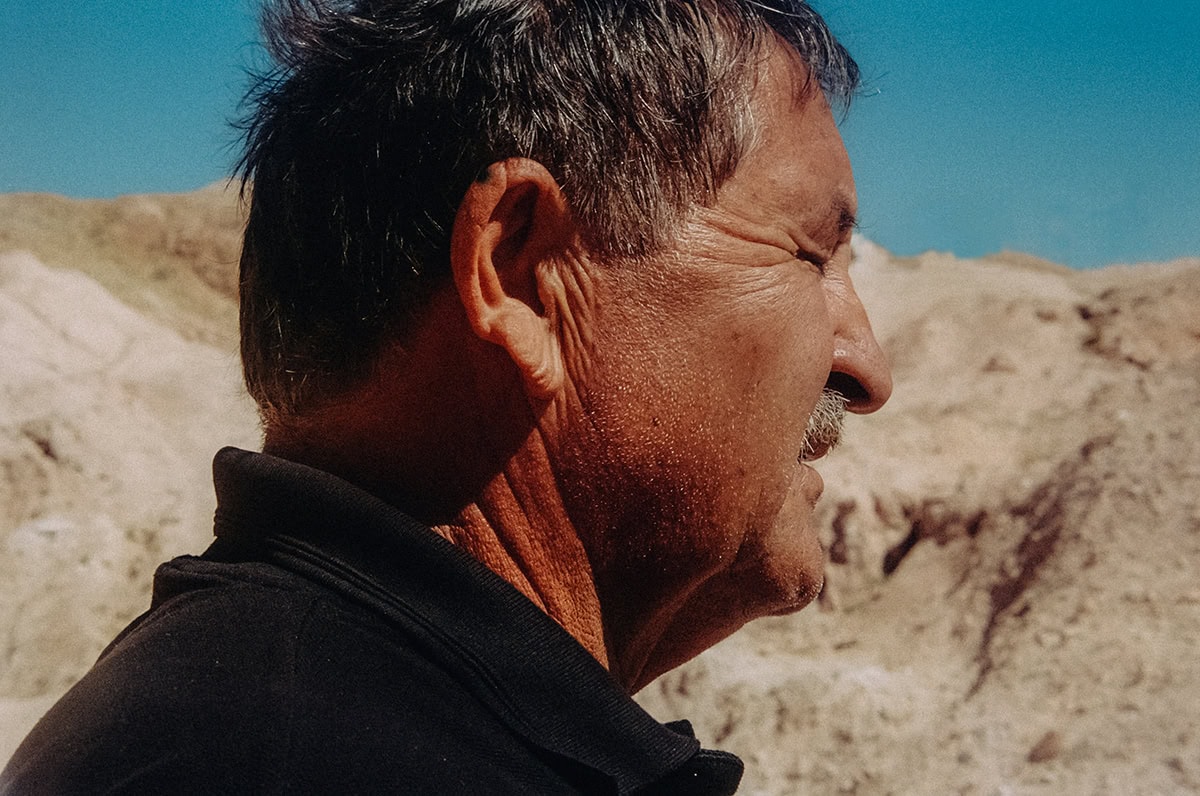

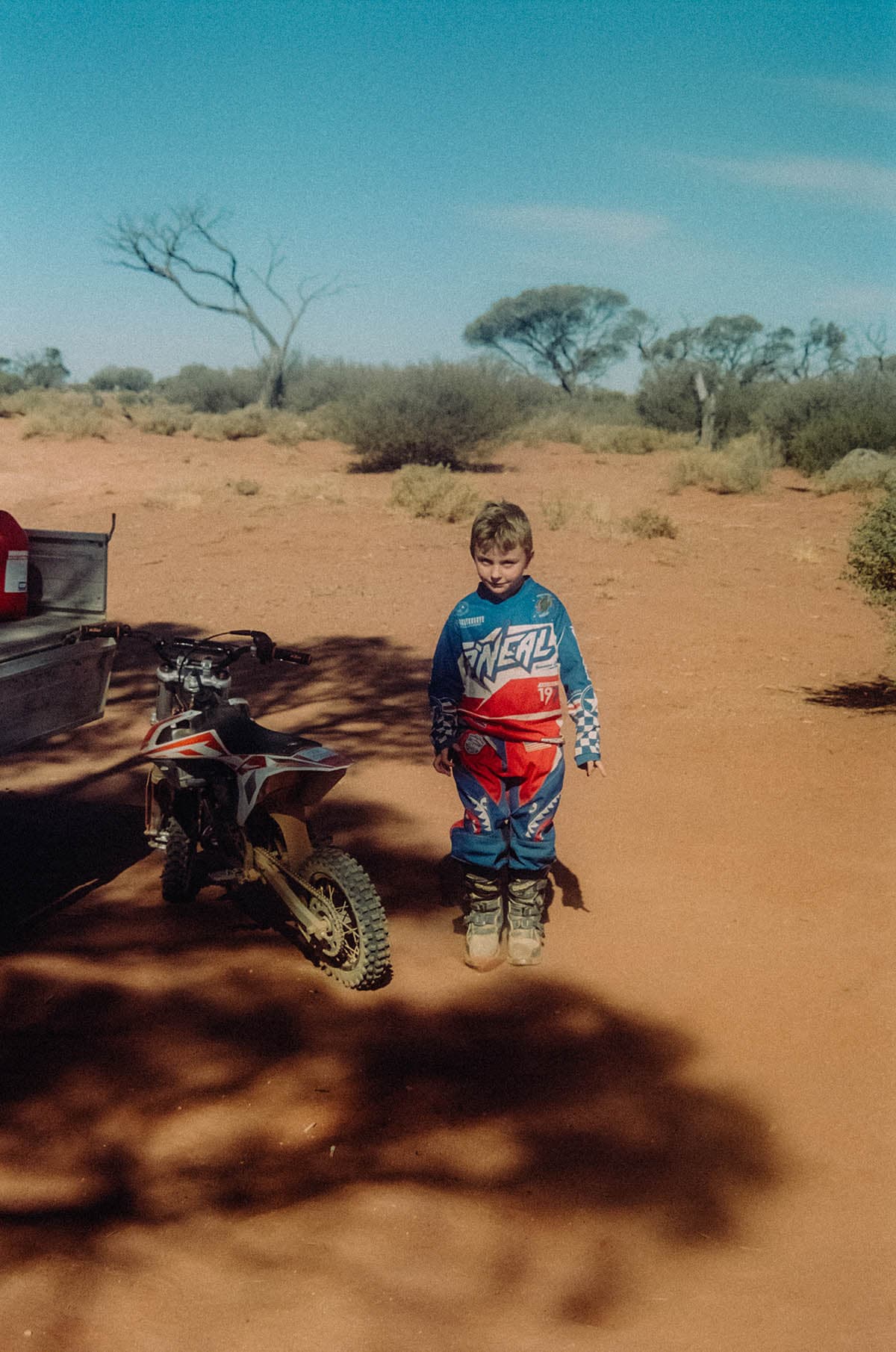

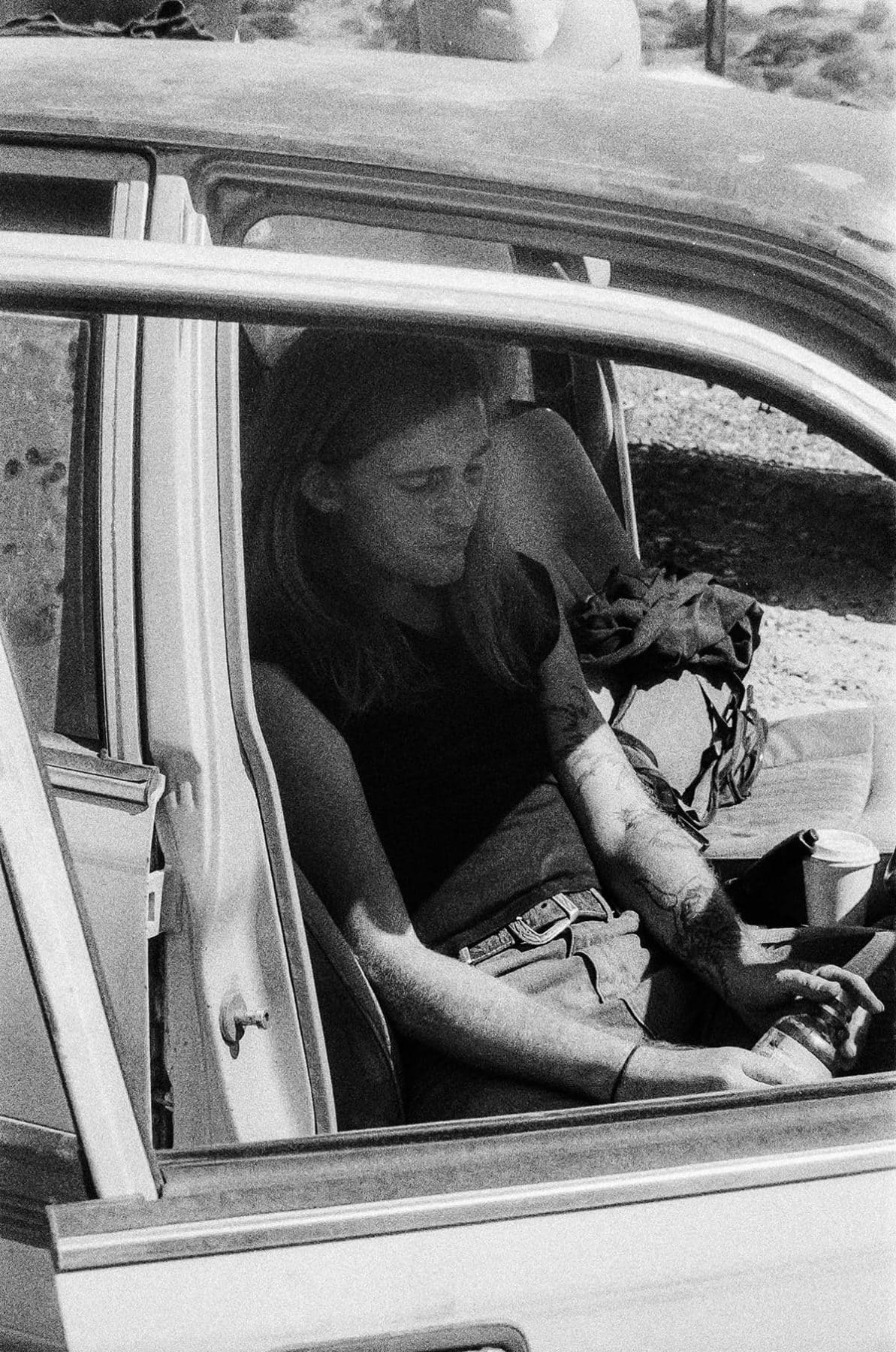

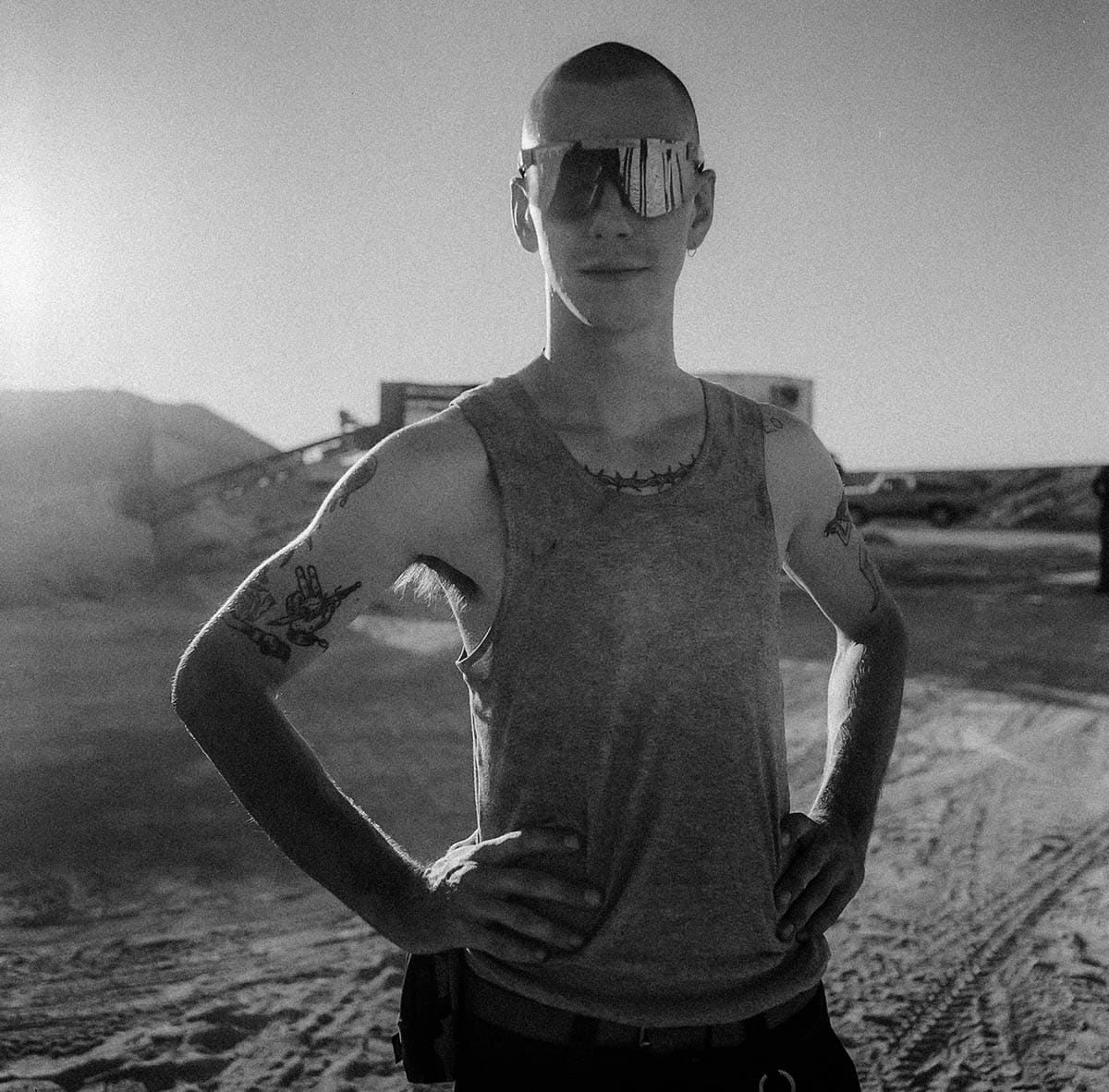

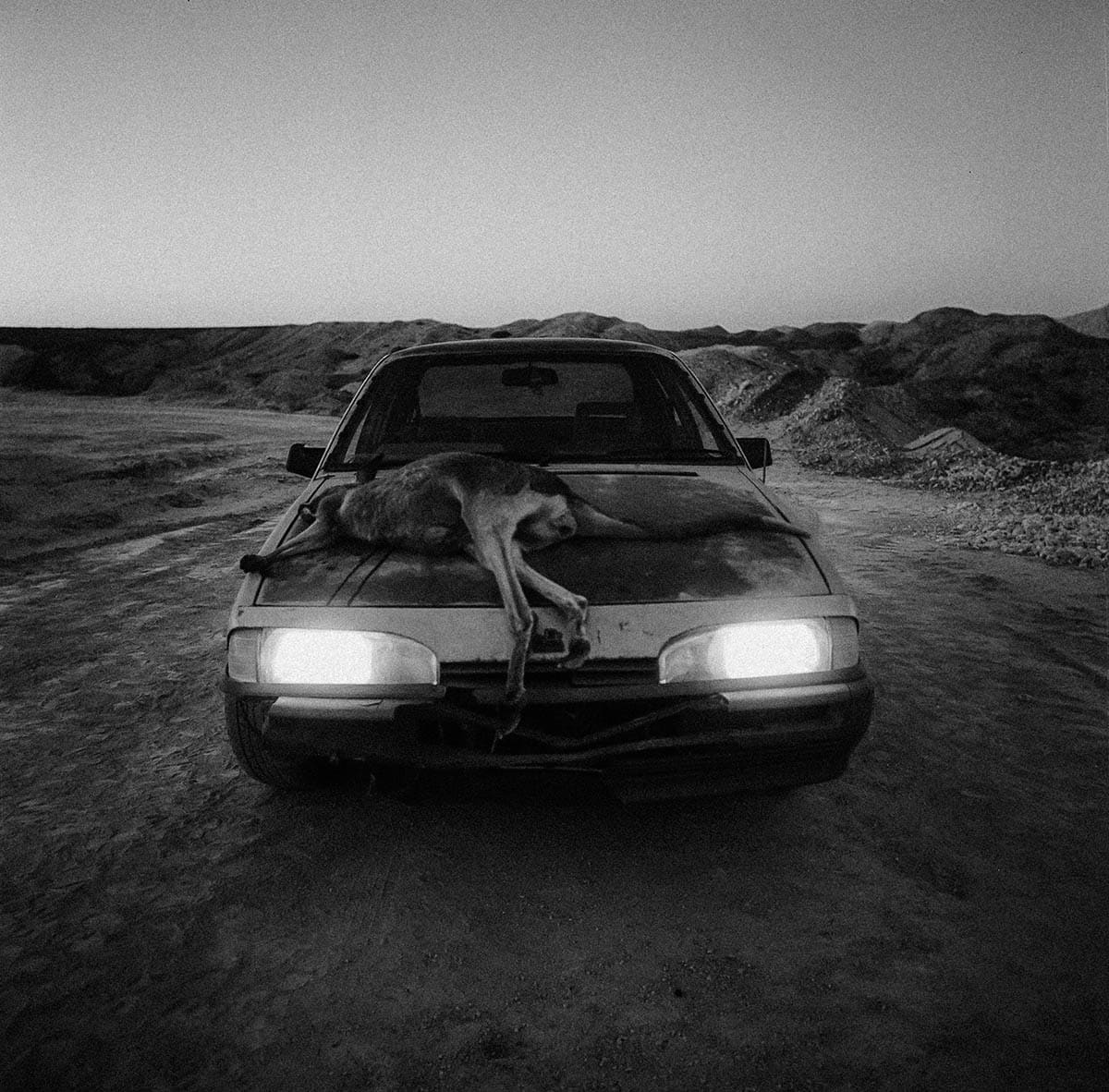

“The Sand That Ate The Sea” was made in conjunction with a mythic film I wrote and directed in Andamooka – a South Australian Opal mining town. For me, Andamooka has a great conflict within it – a conflict between the hard, realism of the Australian working man’s world (and the unforgiving climate of the that land), and the innate mysticism of the endless horizon of the Australian red dirt.

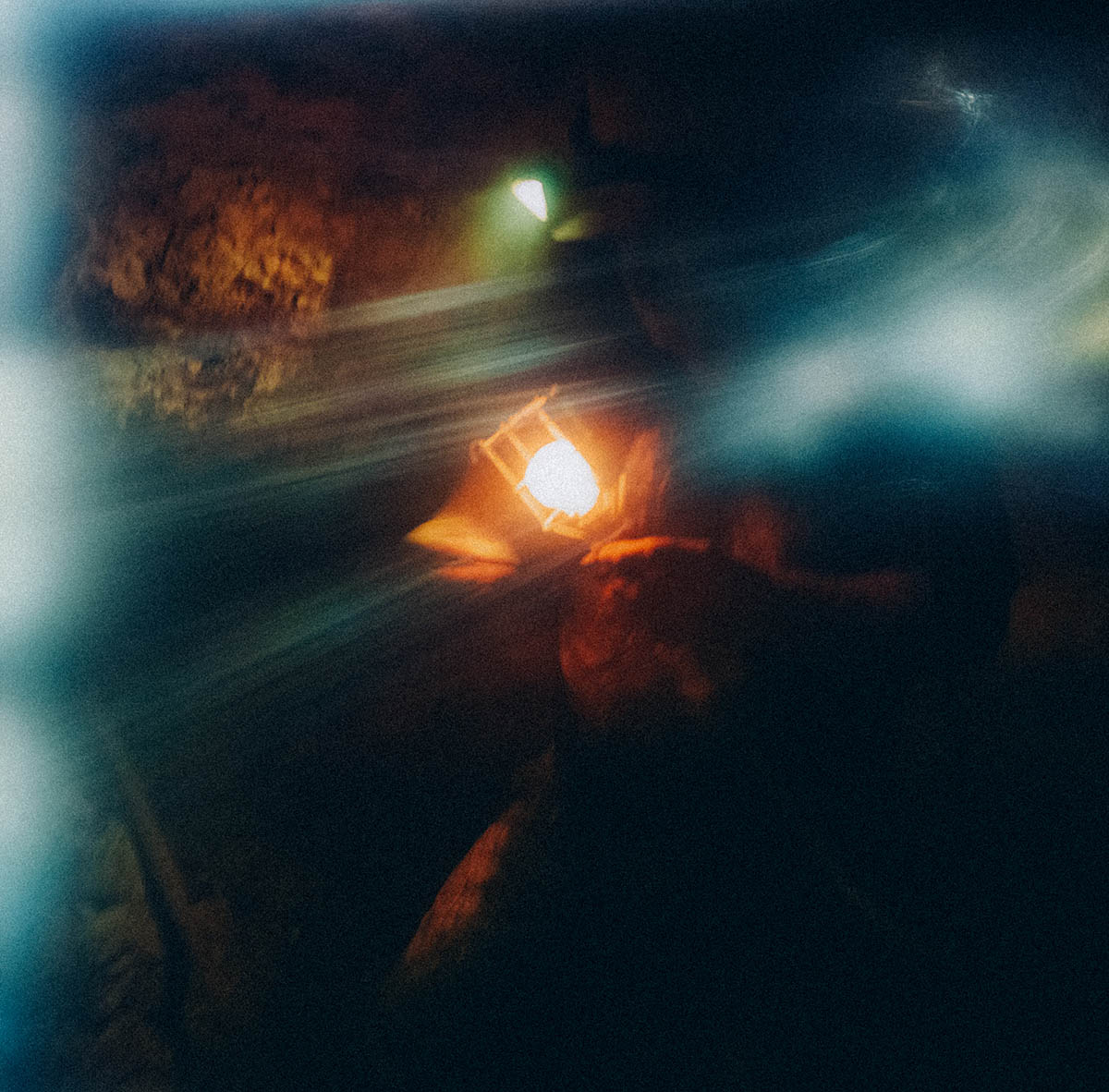

I grew up in South Australia and the desert was something incredible to be exposed to as a child… and also something very magic. I think something about that experiance stuck with me. About the vastness of the land, but also that stillness. That endless horizon (and your place within it). I think the project was a farewell to my birthplace in a lot of ways. It was this goodbye to that land, and that energy that I knew – and also a farewell to my father and those lessons he’d passed on to me. It was shot over the course of 6 months on and off living in the community, and was shot entirely on film (medium format, and 35mm) – the first project I have shot entirely this way.

How do you hope the readers will react to The sand that ate the sea, ideally?

I don’t really look for any specific reaction – I just hope that it connects with people in their own way. And is that thing that all good art is – just a means to your own meaning, and feeling. Something I’ve noticed in showing and sharing my work is how many people come up to you and tell you a story that the work reminded them of – or evoked for them in their memory. And very, very rarely are these ever stories that I feel have anything to do with the work… they are almost always entirely tangential things. These little moments of their life that they feel compelled by the work to share. But thats the beauty of work that really speaks I think – the ability to be referential within your own mind in its connective power.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on The sand that ate the sea?

Absolutely – many things… there’s a great Karl Largerfeld quote that I love: an interviewer is allowed enough time with Karl to ask him one question… and he asks “What things influence you?” and Karl points his arms up into the air and says “zillions… I am like a building with a TV antenna… I just receive, I don’t analyse.” I think thats very much how it is for me – I feel so many artists whose work stands the test of time tend to be influenced by many different modes and thoughts – they aren’t just influenced by other photographers or painters – but are influenced by musicians, thinkers, politicians, philosophers, physicists, botanists… There’s something a bit like interpreting a Rorschach test in any art (and how it works on you). And for me I think thats where I am interested in making work, at the intersectionality of things; the real and the not real, the documentary and the constructed, the human and the inhuman… how these things drawn meaning from one another and in relation to one another.

And there was something unique there in Andamooka; in the people – but also in the place. In the mysticism of the Opals themselves, but also this anthropological (or psychological) interest in what choosing to Opal mine says about people. What kind of people chose to move to the town at the literal end of the road? There was something interesting in that to me – and it felt very connected to my life, my childhood on the road and in the desert as a South Australian. That I think inspired me…

What does photography means to you? What is photography for you?

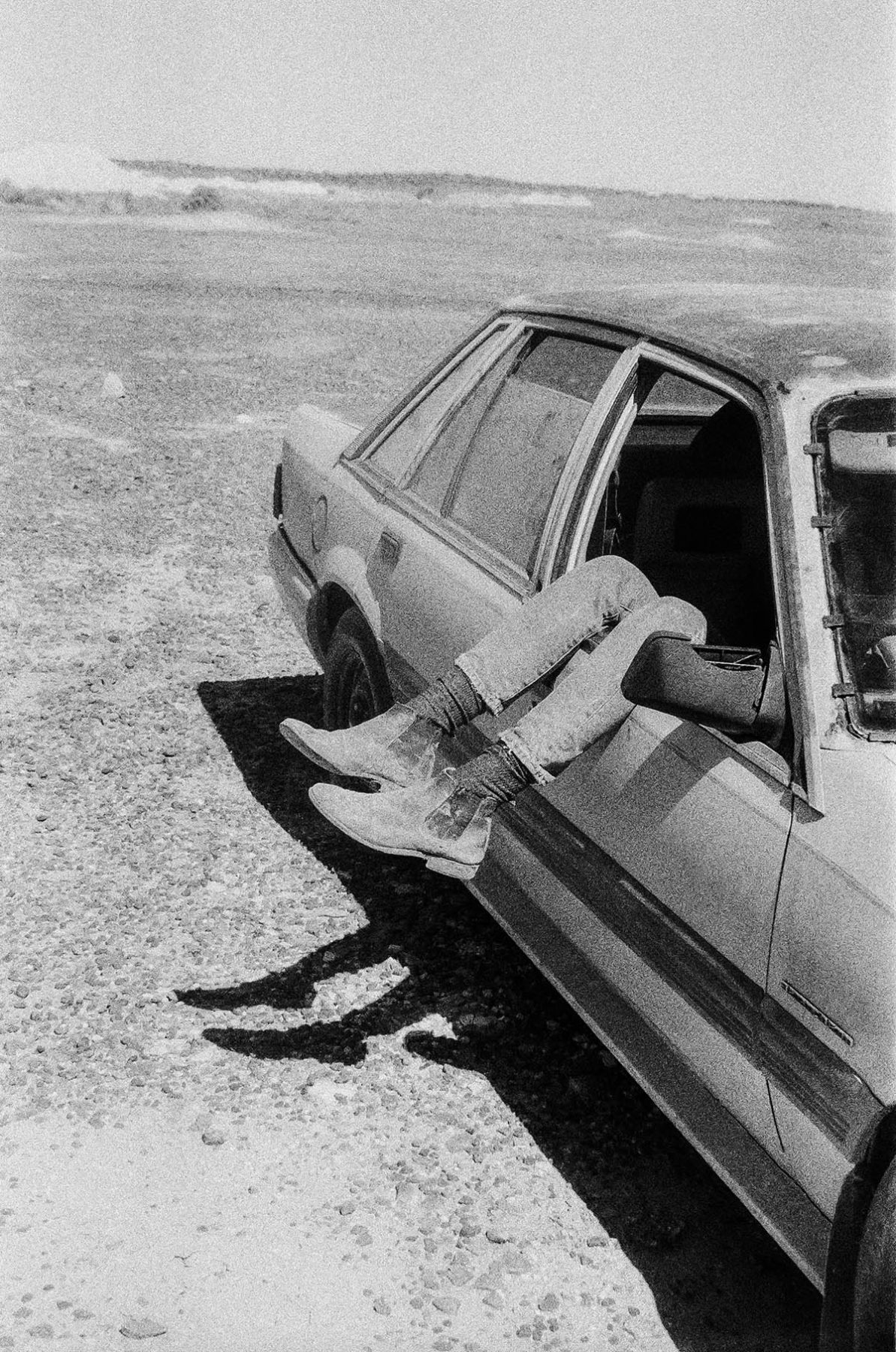

Photography is time isn’t it? It’s the measure of time, and the system of marking it. It’s this thing – you know… we never had a way a to really mark moments in time for so long in human experience – I really believe we’re not designed (as animals) to see time.

We’re not really designed to function as beings with time accessible to us – we are designed to function in an ever changing ‘now’. How photography manipulates that instinct within us… and how the work can feel its way through the sticky medium of time… I think thats what photography is for me. And I think that it is really interesting – how image making (in film and in photography) can take a moment and make it ‘holy’ in a sense… Make it more that what it was in that moment it existed – and in doing that say something about us (or to us).

And I think that you can still feel that difference in how time is in communities more divorced from urban modernity (in the Australian outback, in the mountains in South America… or in more rural areas in Indonesia particularly…. but everywhere).

What led you to the production of this project? Why did you decide to give it this very impressive title?

I made the work very much because of the death of my father – and my connection to that South Australian land. I think just that desire to explore those two things together was what pushed me to do the work in particular. That and this feeling Ive always had, that you have to use the life you get… do something with it… there’s a great Bukowski poem called The Laughing Heart… in it there is this great opening stanza – “your life is your life, don’t let it be clubbed into dank submission… there is light somewhere,it may not be much light but, it beats the darkness…” For me that light has always been the work.

As for the title – I don’t know… I remember feeling like it was right in what it meant, that it was this representation in my mind of how storms would wash over the desert like nothing had happened. How in that land it could flood with rain, but then the dirt would always drain it away. And then when I was in Andamooka researching the film, and taking photos – I learnt that Opals are actually formed from rain and water and sand mixed together; so they are the result of ‘The Sand That Ate The Sea’.

So there was some kind of accident of connection in it as well – absolutely. But it just felt right, and always was there, from back in draft one of the script – before it was even set in Andamooka.

What’s your favorite drink?

Very weak, very burnt, almost stale, percolated black american style coffee – ideally served in and endless cup – and ideally served from becks cajun cafe in the Philadelphia market.