Lao Xie Xie is a lens that captures the emotions of those behind the car and mixes them with the raw Chinese reality.

“I m not the kind of person who takes pictures of one orange and wants to represent the hungry in the world, I go straight to the point, I hate bullshit. This project is a reflection of one part of myself, But also a clear image of what’s the Chinese Gen Z represent. A generation trapped between the poorness of their grandparents, the materialism of their parents and the addicted images of themself inside the social media. An online shout to say that they are different, in a Confucian society and in communist theory that preaches social equality that does not exist and that does not allow transgressions as in Western.

About Shanghai No Why – words by Andrea Baldini:

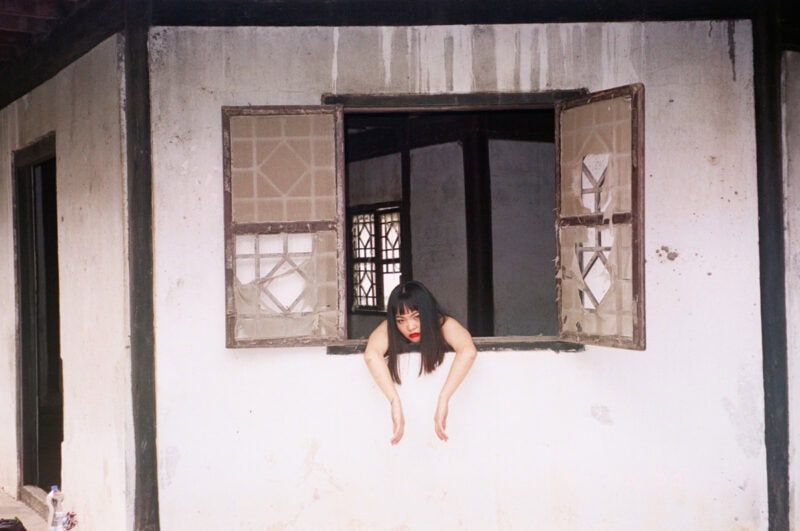

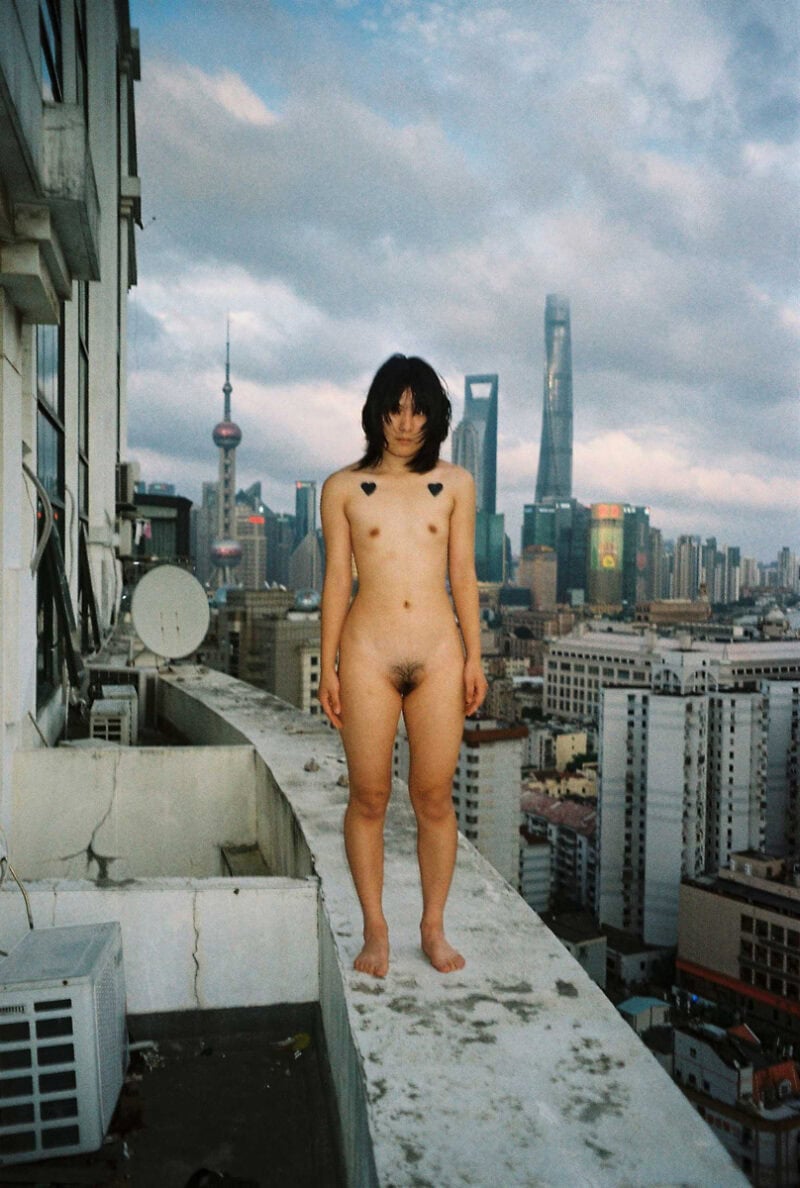

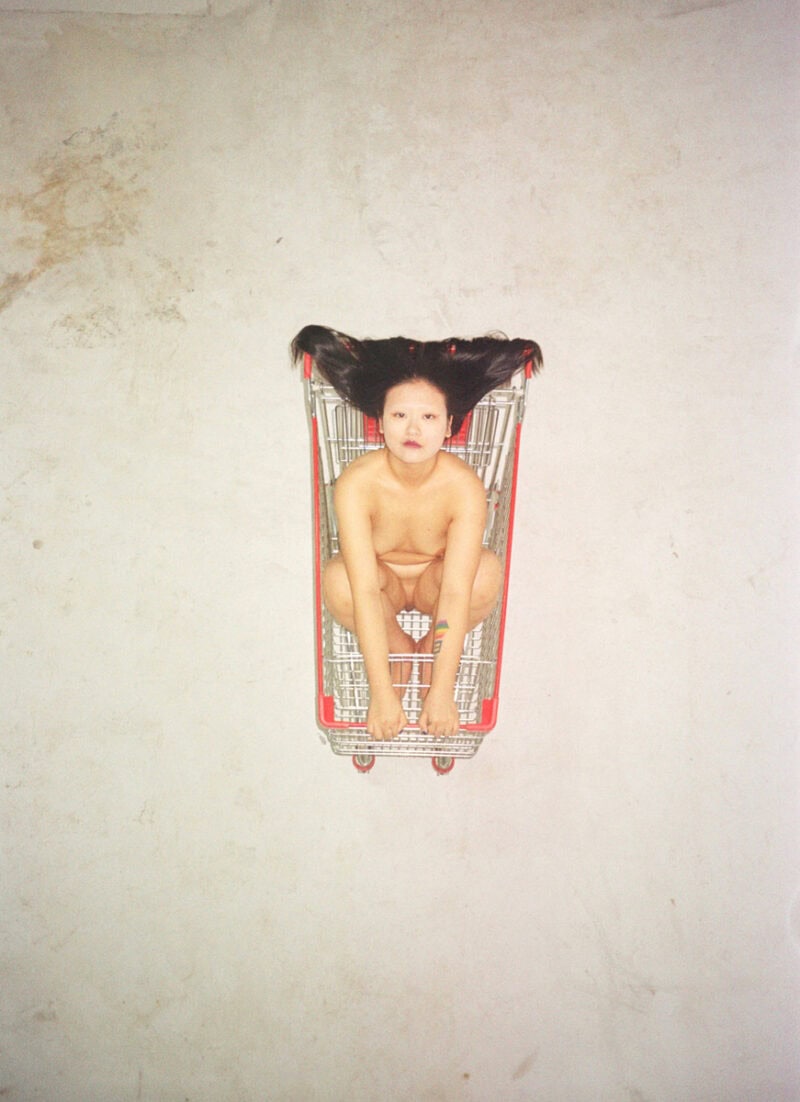

A girl sits in the middle of a field of watermelons. She’s almost buried in the brightly colored fruits. With her green dyed hair, she looks like a modern Daphne between East and West, as the title tells us: She seems about to transform from human to plant. And yet, in this image, there’s nothing of the tragedy and the violence of this myth, where the nymph is turned into a tree by her father as a way to save her from Apollo’s sexual assault. Quite the opposite, there’s joy and life. She seems in control – she’s on top of her surroundings. She’s not a victim: Her gaze is telling us that she wants to be there. This work is a perfect embodiment of Lao Xie Xie’s artistic vision, in between past and present, sex and love, perfection and imperfection. With his camera, the mysterious artist investigates the world of contemporary Chinese subcultures, which appear entangled in a web of contradictions that are a spur of creativity. Historically, we are witnessing perhaps for the first time in the modern period a rise in individuals embracing alternative lifestyles, whose boundaries baffle not only traditional expectations of Chinese society, but also the beliefs of more receptive sensibilities. As in many cases when looking at countercultural movements, China’s generation Y why is using sexuality to explore and fashion their identities. And, in his quasi-documentary work, Lao Xie Xie often places sex and gender at the center of his camera. Though his images are often explicit, they are never simply voyeuristic or erotic. These photographs are far from the idealized and flawless mirages that advertising and the sex industry usually sell us: They are as raw as the chicken that sometimes appears in his shots. Lao Xie Xie photographs real bodies, with their defects and rather mundane features: For dominant beauty standards, some have too much hair, others not enough, some are too skinny or too short, and their genitals are not of the supersized kind found in pornographic imagery.

Lao Xie Xie’s raw realism, as one might call his photographic style, finds in the imperfectionist possibilities of analog photography the perfect ally and expressive tool. The vintage quality of his images clashes with the cutting edge content of his works, creating a visual dissonance that is in turn a metaphorical and metonymical representation of the cultural transformation that he’s investigating. The lack of control in terms of lighting and exposure, mixed with a refusal to bow to photoshopping, opens the door to imperfectionist possibilities. Though in the Western world perfection has been considered the goal and sign of good art, Eastern aesthetics has often embraced the expressive power of the defective. With its rough edges, blurred representations, and incomplete forms, imperfection stimulates the imagination and brings to the table possibilities of meaning-making that are unknown to the smooth surfaces of perfectionist art. In this case, it forces us to actively engage with the work, while at the same time building a continuity between his art and our everyday: We feel like we’re part of the picture as if Lao Xie Xie’s reality were ours. The influence of Eastern aesthetics is deeper than this sympathy for imperfection: It also touches upon the chromatic palette and the imagery populating Lao

Xie Xie’s raw materialism. The colors are as bright and powerful as one can find in traditional Chinese culture, whose visual boldness sits in stark contrast to the timidity of Western visual culture. Both traditional and commonplace artifacts of Chinese origin mingle here with naked bodies, entering a kaleidoscopic dance of art and life that echoes the Dionysian spirituality of ancient rituals. But don’t be misled: There is nothing beyond these appearances. As Lao Xie Xie tells us, there’s no “why” – only “is,” as one could add. There are no pretentious meanings to be revealed or unveiled, no ultimate prophecy to be decoded, and no final life lesson to learn: No message of ultimate freedom or liberation, nor claim to undiluted authenticity. More than a prophet or a guru of alternative life styles, Lao Xie Xie is a bystander – almost an outsider of his known creations. There is nothing more than what you can see. But, as Oscar Wilde used to say, “it is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.”