Jonathan Glam is a multidisciplinary artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Through photography, video, writing, sound, and music, Jonathan addresses and confronts personal and collective societal patterns that reflect histories of systemic violence and means of survival.

Using queerness as an act of futurity, radical intimacy, and storytelling, Jonathan’s work offers an alternative path to the realities we are conditioned to today. Jonathan’s work aspires to question performances of obedience and create new spaces for experimentation, liberation, and shapeshifting.

His language is sharp and a little melancholic as if the union of both could foster the attention, and subsequently help the growth of awareness.

About ‘Box’ – words by Jonathan Glam:

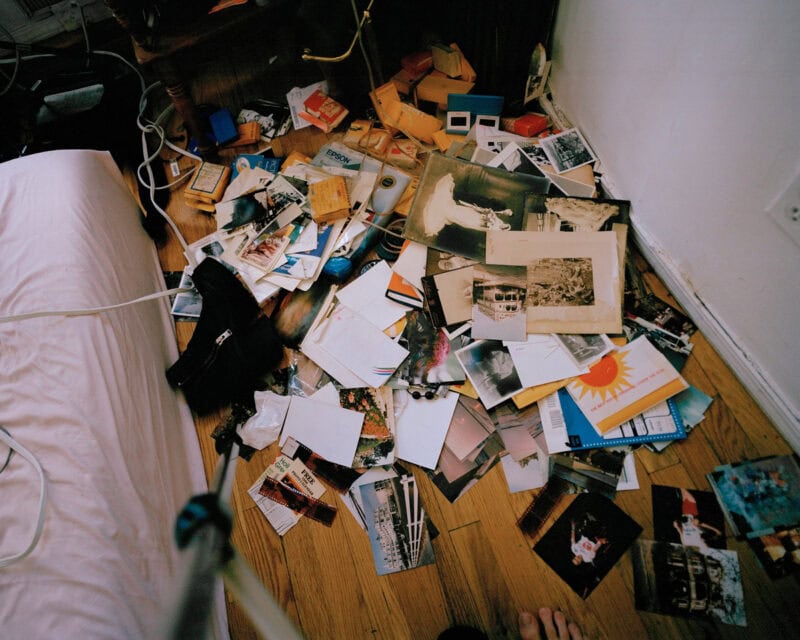

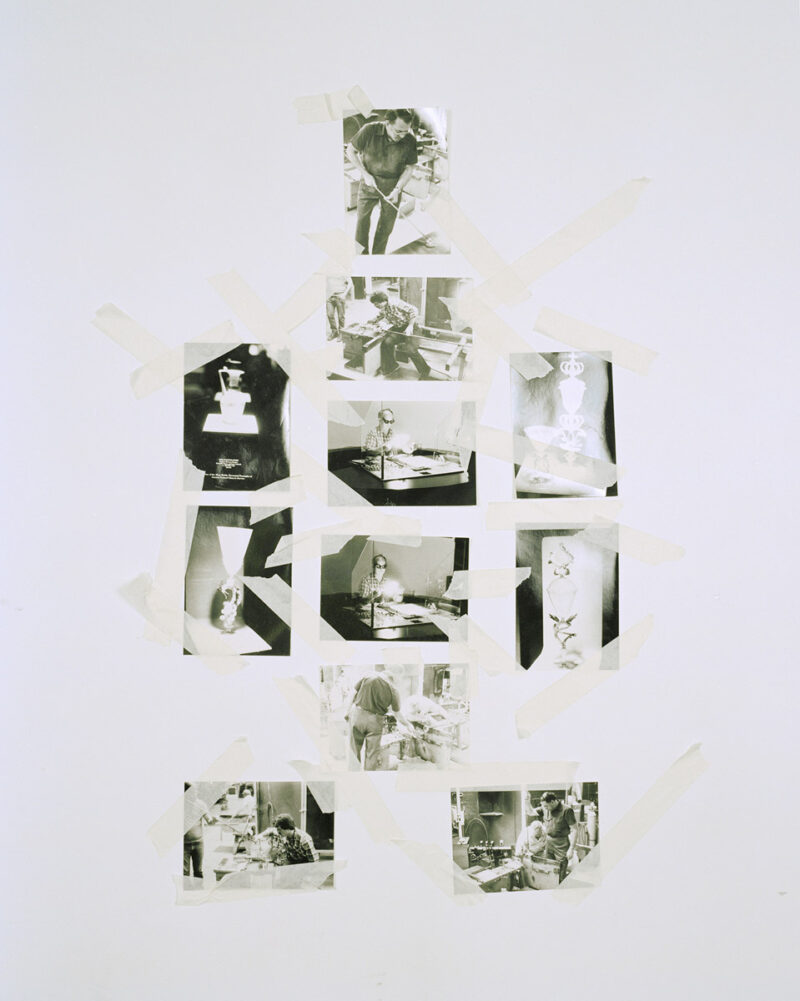

On August 4th, 2019, I went to the 14th street flea market. I stumbled upon an old, moldy, and deteriorating box, right by the entrance of the market, filled with photographs, negatives, slides, and film. I started looking through the images and negatives, trying to find some photographic gems I believed at the time were worthy of saving. When looking through and trying to choose the material I wanted to buy for myself, it started drizzling, a drizzle that very quickly crescendoed to a mini mid-summer monsoon. I purchased the soggy box for twenty dollars from a very nice man that helped me put my new materials in several used plastic bags, as it was impossible to carry the wet box. It completely fell apart as a result of the surprising rain. I took the bags back home and decided to put them aside and let them dry for a day so that I could look through my new purchase without getting my hands too wet and tearing the moist and sensitive photo-papers. The following day, I sat down and started looking through the dry photographs, tearing them up from one another, as the transition back from wet to dry made them stick together. I sat in my room looking at the scarred photographs with the damaged skin, knowing that unlike a skin like mine, the skin of an image will take much longer to heal.

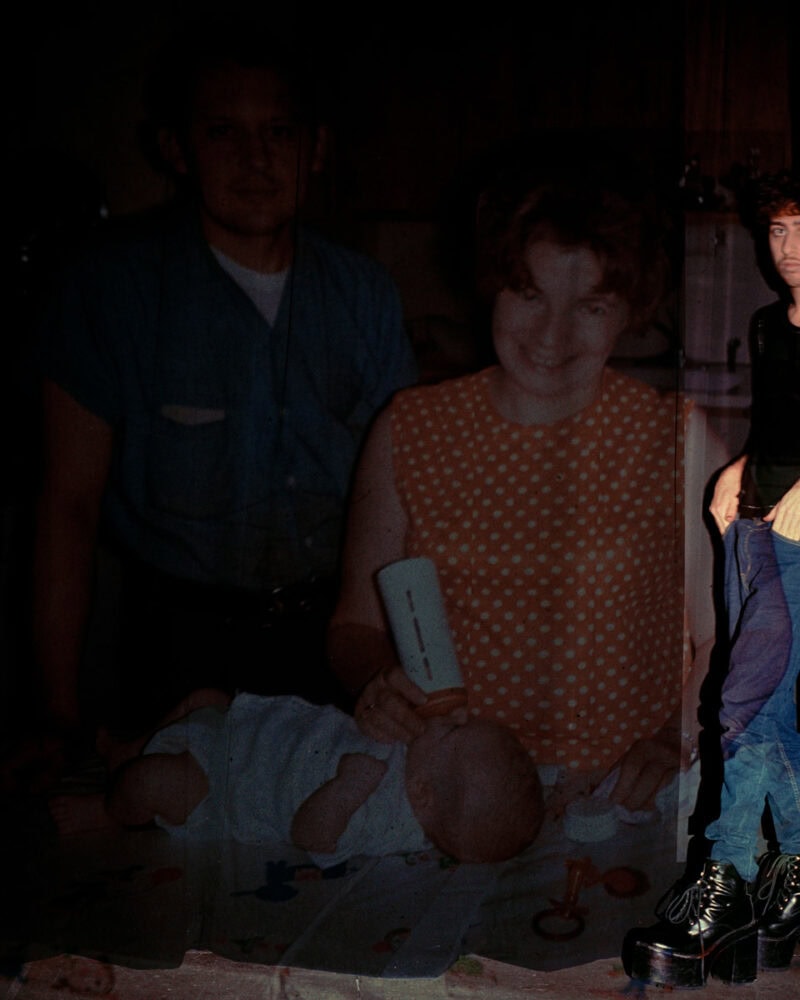

Looking through everything that I found, it was hard to understand what linked all the photographs and imagery together. In that box, I found a collection of hundreds of photographs and slides dating from the 1890s to the 1990s. Negatives of neatly dressed people from the 1920’s next to an Ektachrome slide collection of racing cars from the ’80s, and family polaroids from the 60’s next to a group of closed-up digital pictures of flowers. It seemed to me that the bigger picture was bigger than I expected it to be. After spending more time with the material, I started recognizing patterns of subjects, places, and people recurring in the photographs. I noticed that the same surname appeared over and over again on the envelopes of some of the films and pictures from the ’60s ’70s and 80’, but it does not appear on all of the items in the box.

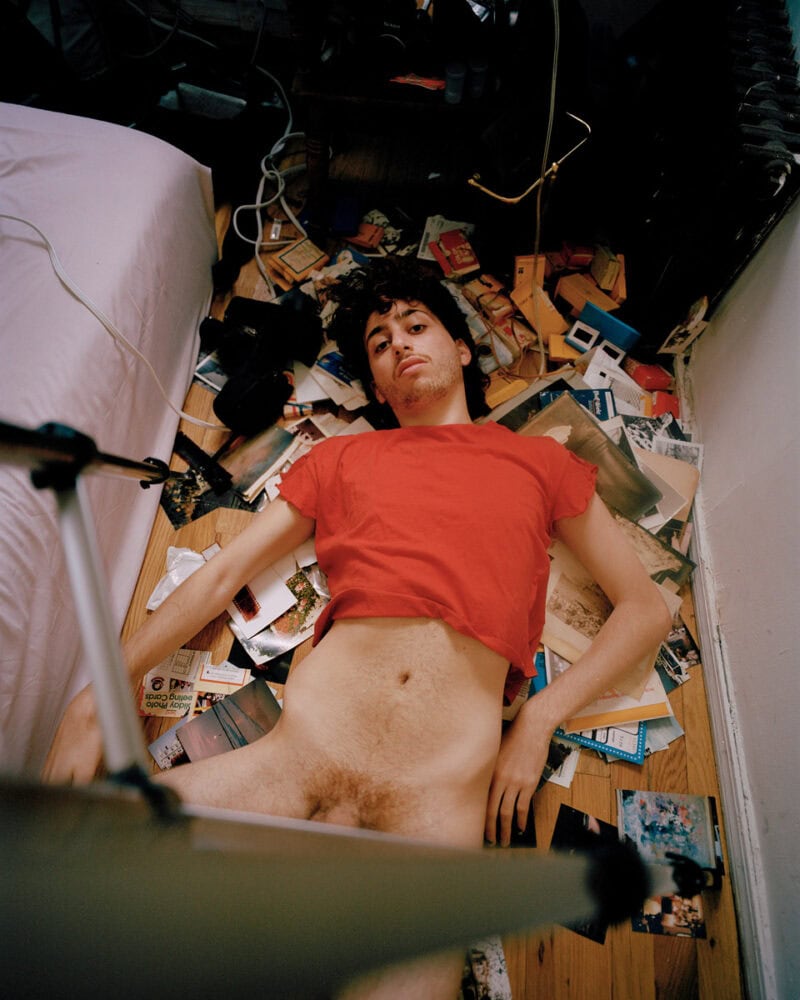

The archive covered my bedroom floor for two weeks after I bought it. I kept looking at the photographs, trying to understand and find the reasoning for this collection to be together and discover the specifics behind the contextless symbols I found. I started piecing the puzzle in my head and manipulating the information before me in a way that made sense to me. I was reading the symbols and imagery and forcing them to a narrative that existed in my head before starting to question the violent nature of what I do. Is this private family archive, that I am not a part of, just as limiting, and at times violent as any other archive? Is it right for me to seek validation from this archive and look for myself within it?

My thought process shaped and manipulated the weight and meaning of the photographs, as the context of the images kept changing when I looked through them. It might just be that this kind of fragility is the weakness of every photo archive, and, our entry point. To understand the way we construct our personal memories through photographs, we must also understand the way we create larger narratives through photographs, we must question the way we create and preserve our fantasies, and ask who gets to be a part of them.

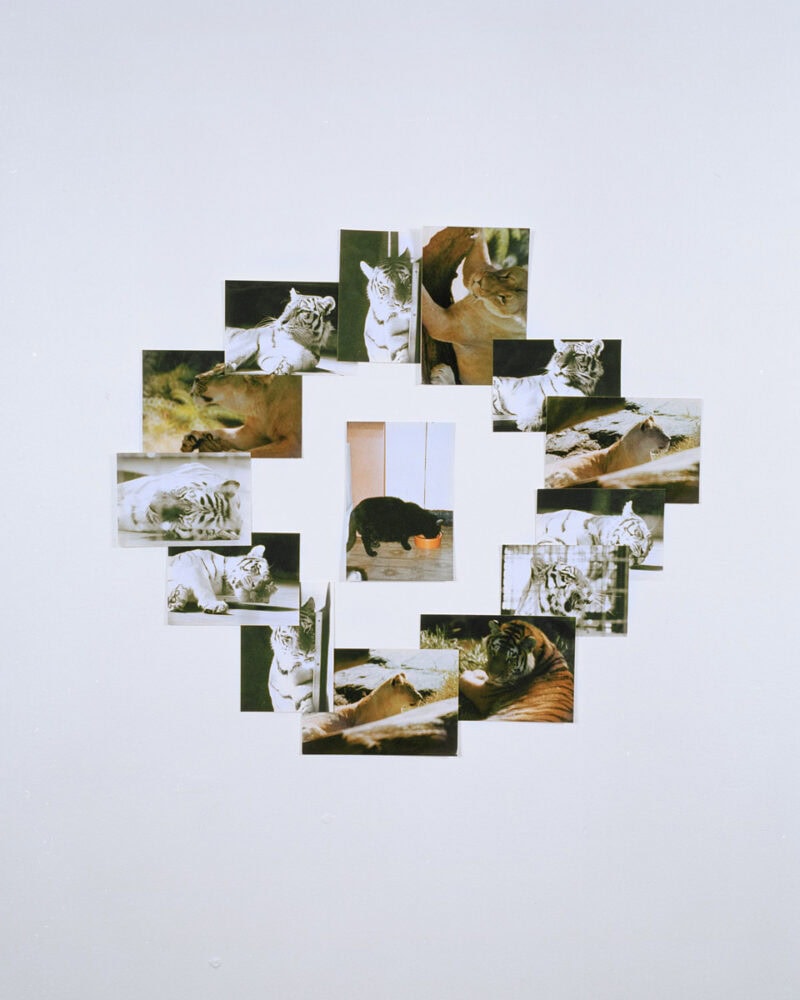

I started inserting myself to this personal archive, both by rephotographing the materials I found in that box and with my body. When I first got my hands on this archive, my efforts to save it did not stop it from tearing apart, fading away, and deteriorating. Now, I am discovering that the materials I found continue to deteriorate, probably faster than before, when I use them for my photographs and my interpretations. Maybe, deterioration is not necessarily disappearance and death, but another form of shapeshifting.