«By the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs. […] The cyborgs is a condensed image of both imagination and material reality, the two joined centers structuring any possibility of historical transformation.» (Donna Haraway)

In her book Staying with The Trouble, American anthropologist and academic Donna Haraway uses not only science fiction but speculative fabulation to empower new forms of narration to navigate our schizophrenic times: through her fabulations, Haraway helps us to envision an ecosystem of cyborg species, hybrid texts, creatures of fiction and words, that rise from the tensions of the stories, history and images that populate our surroundings. She describes cyborgs as creatures of social reality as well as creatures of fiction, a mix, or a remix I would argue, of both truth and myth. Something or someone that flawlessly embodies the hyper saturated, convulsive landscape in which we live.

In what he himself defines as an «inconsistent essay» published in February 2020 on eflux and dedicated to Italian poet and novelist Nanni Balestrini, Franco Bifo Berardi describes his late friend as, among other things, a recombiner. Balestrini was a poet who did not write words. His work, he said, was recombining. Recombination is a task for us too, and we should take our cue from him. But the question is: recombination of what? The recombination of meaning, of language, of desire, of pleasure. «Poetry is the consistent and intentional recombination of what exists, with the aim of creating what does not yet exist», wrote Bifo. If the desire to reappropriate and recompose, to form hybrids and cyborgs and create what does not yet exist was a choice for Balestrini, for us it is an “instinc”, as The Bells Angels tell me in this conversation. An unavoidable 21st-century condition that cannot escape the intrinsic heterogeneity of processes of recombination. As I dig deeper into the layered work of The Bells Angels, I can’t help but see them as recombiners, creating a story in the present that does not yet exist, but which is taken from a myriad of stimuli, objects, gestures and stories, layered together in a very meticulous process to interpret the absence of truth yes, but also to amplify its possibilities.

REMIXING THE ARCHIVE. For centuries, individuals and groups alike have attempted to manifest their intentions, rules, ideals, stories, morals, and values by enclosing them into boxes: archives. Some are elaborate accounts, others are concise, hermetic, and straightforward impositions of narratives. Some have called them archives, but others take the name of imposed truth, documentary, or representation. Similarly but with a more subversive attitude, artists have recreated their own archives and reinterpreted others, often challenging the structural and passive orientated version of the archive, giving us the chance to move within and through an archive, to see through it and to acknowledge its points of view. «Truth is a thing of this world: it is produced only by virtue of multiple forms of constraint.

And it induces regular effects of power. Each society has its regime of truth, its “general politics” of truth: […] the techniques and procedures accorded value in the acquisition of truth; the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true» (Franco Bifo Berardi). According to Foucault, power is diffused not only through the institutional apparatus of control but is intrinsically part of all the elements that traditional methodology and systems deem objective and acceptable: quite simply, the archive.

But archiving today has become a form of remixing, archives should be works-in-progress, sponges, living cyborgs populated by past histories, underground narratives, future visualisations, personal and collaborative emotions. They are remixes: attempts to merge experiences and mix up beliefs and contradictions that can eventually liberate us from the barriers of a defined structure that simply does not exist anymore. Dead archives have been the basis of culture, a culture that feels way too scripted, way too edited and adjusted. Their structure resonates because of their violent attempts to dictate linear narratives. Call it remixing, recombining, archiving or what you will but the truth is that as someone living today, I feel as though my fractured identity can only breathe through a cultural mash-up, within the manifestation of the contradictions we live in and which utilises a remixed language that enables different tensions and points of view to be taken into consideration, and heard. Here I chat with The Bells Angels about visual and poetical cross-pollination, mash-ups, and the assemblages of media and temporality that allow them to remix their truths and fictions.

First of all, tell me about the three words that have been echoing around your studio for the past six months, and how they have influenced your recent work?

Science-Fiction, landscape, invasion.

By compiling, collaging, and distorting you’ve created a repetitive code, a sort of black-and-white rhythm with glimpses of faded colour that reminds me of the modus operandi typical of fanzine production, or a mash-up DJ set. How did the urge to remix became such an inevitable way of thinking when it comes to interacting with the materials around you?

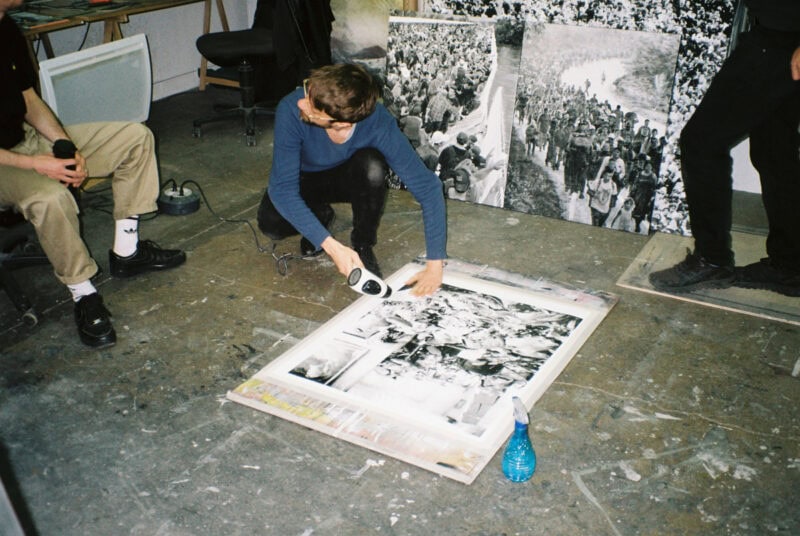

We actually grew up in the postmodern era so this process of remixing is instinctive behaviour. We have been into appropriation since the mid-90s, using pre-existing images, questioning the words original, copy, and reproduction. All with an inward impression of permanent loss that was transmitted by the previous generation (boomers) saying that everything has been done, it’s the end of history. From a DIY perspective, we engage in recycling an ever increasing quantity of data, images and archives, each of us in different cultural fields ranging from counter culture to mainstream. Starting from the idea that everything in culture is a kind of living-dead thing. We make representations from representations in order to make them speak and exhibit them, like a corpse ventriloquism. We are in a world where science-fiction has become reality, we grew up with 80s sci-fi movies, a true dystopian space for alternative realities and narratives. «Nothing is true – everything is permitted» (W.S. Burroughs). We were 25 at the turn of the millennium so we got up to a lot of analogical things as teenagers (collage, graffiti, analog photography, Xerox, etc) that we naturally evolved within the digital age, adapting strategies from musical techniques – such as editing, sampling, looping, distortion, delay, echo, etc. – to the graphic-pictoral field. This is easy thanks to the democratization of software such as photoshop, which is used today by 90% of people working with images worldwide. Today everybody process images and texts, they cut, past, edit and filter to produce their own design and identity, so we are all producing potential alternative facts, we spend most of our time behind screens, operating in a hyperreality in which categories of subject, body, machine, text and images have become muddled by the evolution of technology. As the present era evolves with the pandemic, it is becoming totally operational, integrating technology into every aspect of personal and civic life. We all know that information and images have a program, that they are encoded with specific meanings and speak within specific contexts through dissemination strategies at times political and cognitive but which always play with our basic feelings and desires: nostalgia, fear, greed, love, sex, beauty, chauvinism, and so on. We always think in terms of meaning, origin and quality of images, we love images, are suspicious of them and very careful with the semiotic. An image extraction from Google is a gesture of abstraction. Without context, meaning is relative. With the democratisation of Deepfake, reality is relative. «Technology does everything for us, so we no longer have to operate in terms of experience. We operate in terms of aesthetics» (Jack Goldstein). Humans are biohazards, machines are not. We use machines to control the production of images, the tools of industrial capitalist visual culture. We work with many different processes and machines to generate our paintings, we use various technologies from the archaic – painting and airbrush – to software – printers and screen printing. We want our paintings to have a physicality, the process behind the series is about being engaged in the treatment of images in a physical way, to improve it, in terms of production and usage. In the age of digital reproduction, our work demands that we reappraise what it means to represent and to recall, questioning the habits and conditioning of the viewer, the revenge of the real if you will. We produce image-based paintings that explore a self-destructive civilisation. It is important that it be a complex technical work with various layers and techniques in order to give physicality and scopic drive to a large-scale processed image. We want the viewer to be faced with the spectacle of the world, questioning the subjective relationship that we all have with images in the digital era.

«To be brief, then, let us say that history, in its traditional form, undertook to “memorize” the monuments of the past, transform them into documents, and lend speech to those traces which, in themselves, are often not verbal, or which say in silence something other than what they actually say; in our time, history is that which transforms documents into monuments» (Michel Foucault). You often use found images in your work as well as elements that carry their own mnemonic power: you create new archives and you dig into existing archives. Within what I would call the archival possibility of creating stories lies the potential – as well as the problem – of the archive itself: the given idea that within the archive, history as well as memory, can be preserved without being modified. You are clearly distancing yourselves from the idea of a dead passive archive but how do you make sure that the archives you work with stay, in one way or another, alive, discontinuous and anti-monument?

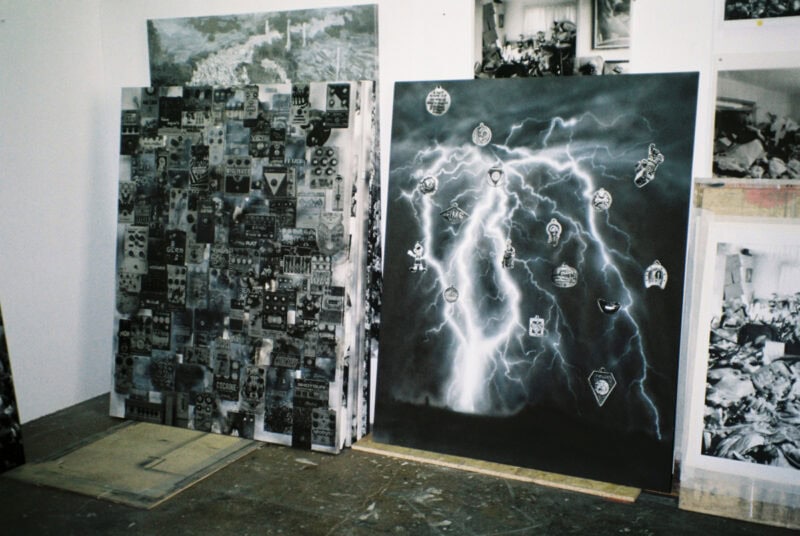

Everybody is an archivist nowadays, the amount of data, files and pictures that we all have on our phones or computers has never been so huge. And it’s constantly increasing as networks and traffic grow. The amount of data generated each day by social media, shopping platforms, financial institutions and other online activities was estimated at 44 zettabytes in 2020, by 2025 there will be 175 zettabytes of data in the global datasphere. One zettabyte has 21 zeros. The world in its entirety has succumbed to the archiving impulse, data is the new oil for the tech industry, we are all feeding this market, we are all recording devices accumulating data. It has become an irrepressible impulse, the cognitive approach of the various devices that surround us is total. So the question of organising data and remixing our digital environment is basic behaviour, hoarding is normal, it’s a pathology in the real world but in the digital world nobody cares about the energy they use or the absurdity of building identities with preconditioned content. We have worked extensively with archives within specific projects, such as the archives of Jim Shaw or with collections of subcultural phenomena, such as a metal music graveyard or a collection of short zombie stories but also projects such as conceiving a retrospective catalogue for institutions such as Confort Moderne and Comédie de Caen.The question of organising a corpus of information is related to power. It deals with authorship and intellectual property. We always try to have a specific point of view, mostly playing with a photo dystopic approach. The context and economy of production always determines the form of the archive, it lies in the memory of the place and/or in the politics of the conceptual field that it’s extracted from. For Confort Moderne, we decided to bury the only copy we made of a large part of the Fanzine Library collection from the Fanzinothèque. This time capsule has been sealed into the foundations of the new building. We may have previously put on a performative display of the archives but it is no longer visible, it’s sealed within a specific time and physical experience of it. It will reemerge in a hypothetical future. For the Alterzombie project, we destroyed the exhibition just before the opening, we gave away books for free and played the soundtrack we commissioned from Antoine Kogut and Nico Motte. It was about disseminating texts and sound and destroying the art works and the white cube by using a repressed figure from popular culture. We like the idea of giving a specific context to an archive and a physical way to experience it. That’s why we use sound and music, it’s linked to the optical experience: how can the image be processed as a sound? How can we hear a landscape and see a soundscape? A picture of a storm makes you hear one. With media images, the eye is controlled by optical rules, distance, scale and frequency; in our recent series of paintings, we produce large paintings to give a physicality to the images we build. Large scale black and white images to avoid any kind of colour induced emotions, the black and white creates an interruption in the contemplation process, it concentrates the eye. It’s about composition and drawing, about the foundations of paintings. Slowing down motion by painting is a precious action in the accelerated age we live in.

You captured many crosses of different shapes and origins, horseheads, band names, occult hands and tiny metal objects with occult symbolic energy for your keychain series. Being obsessed with chains and small random objects myself, I wonder what draws you to certain symbols, what power did you try to invoke or take away from them?

Actually the collection has been growing for years, almost randomly and quite organically. By sheer chance, like physical serendipity. Every object has a specific history, most of the time it belonged to somebody, was in their pocket…Those small industrial objects carry a lot of focus and proximity with human activity at different levels. They can represent religion, brands, logos, the military, tourism, sports, all aspects of economy and ideology, they are all vehicles of identities. The keychain painting series questions identity regarding the landscape: who does the landscape belong to? We can’t look at it as a natural thing anymore, it has been invaded, colonised and hacked. Symbols and brands are like spam on a landscape in a computer screen, that’s the problem that we deal with by producing those large scale paintings. We use airbrushing to paint an out of focus landscape that is only visible from afar, they are colonised by crowds of medals and signs representing human activity. We envision the occupation’s ratio of a crowd within a landscape. In the accumulation process, in the crowd paintings, there is a principle of objectification: every form is seen on the same ontological level, like an interface, extremely frontal. The narrative it produces is a mass of individuals, demonstrating and controlled by images dealing with identity and anonymity. «Civilisations as yet have only been created and directed by a small intellectual aristocracy, never by crowds. Crowds are only powerful for destruction» (Gustave Le Bon).

For the exhibition Models & Scores, you turned a play into a text-generating apparatus. It could be argued that you totally flipped the structure of theatre production, which usually sees the text transformed into a performance. You did the opposite by constantly pushing the boundaries of publishing, turning something that is conventionally considered a 2D practice into a reversed performance. How much further can publishing go (and how are you planning to push it even further)?

Since we are both into music and sound, we work with text within performances and collaborations with authors. The book is a circulating object with specific characteristics, if it looks like a holy book, it’s not approached in the same way as a book printed in Braille about black metal. A book in Braille is necessarily performed in a tactile way, and the Bible is performed by chanting the text. We handle the semiotic context in which we activate narratives, playing with the idea of the uncanny and interchanging media. It’s a way to increase our sensorial, cognitive approach with similar ideas working in different ways with the mind and body of the viewer. We are really interested in sensorial deprivation and its historical use by the military industry, alternative medicines and psycho- logical experiments. This behavioural approach seems central to understanding the technological environment we are evolving in. We often work with blindness and deaf parameters to reverse the position of the viewer, shifting the experience of editorial practices.

And finally, not to shy away from the “why” that has fuelled this page: why The Bells Angels? Why the eye of the storm and lightning in your latest canvas? And why does remixing work better than remitting?

It was the ringtone on an old phone that we used to love. These are disasters, natural or human. We are in a permanent disaster era, we testify to everyday life through media images, those images are fascinating and frightening at the same time, they have a special effect, a quality that mirrors the world’s script, and this time, it’s not sci-fi anymore, it’s the revenge of the real.

Credits

Words by Sofia Gallarate

Photography by Melchior Tersen

Starring The Bells Angels