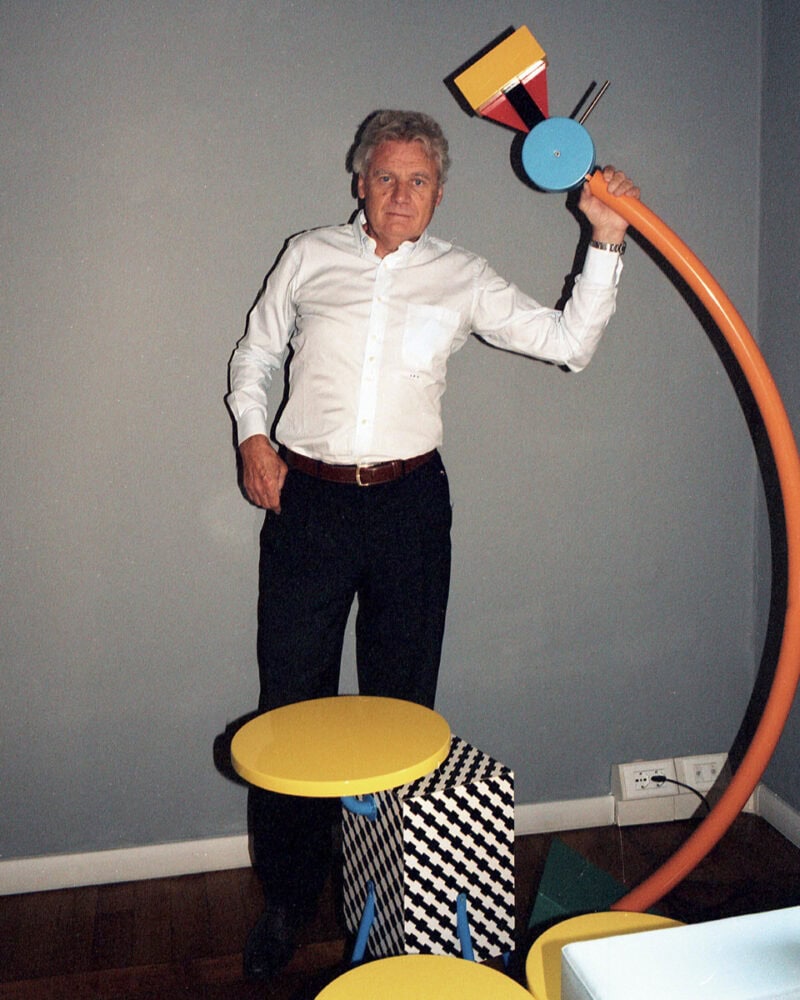

The brand turns 40 in 2021 yet it has never lost the fresh originality that defined it. Accompanied by the surreal lyrics of a Bob Dylan track, with Ettore Sottsass and a gang of young, courageous, and visionary designers behind it, Memphis exploded onto the scene in 1981 with a new vocabulary of shapes, materials, patterns, and colours. Intended as the bringer of the new and adopted as an elitist lifestyle, it articulates an anarchist language that subverts every pre-established order, rebelling against functional and rationalist “mannerism”. The collections kept coming until 1988: homogenous but eclectic, refusing all “everyday banality”, mediators of art and design. Small-scale production and craftsmanship were paired with resounding communication and image, all of which resulted in a powerful expressive impact that nodded to pop culture, colonised magazines, and got everyone talking about design. Memphis invaded much of the creative universe, with forays into fashion, graphic design, and even television. In 1996, the brand changed hands: from Ernesto Gismindi, the patron of Artemide, to Alberto Albrici Bianchi, who still wields the reigns today with the launch of a new online platform designed to boost the e-commerce and remind us of the sheer pleasure of leafing through the pages of this unique and unforgettable story.

For a Modo report in 1983, Ettore Sottsass wrote about the phenomenon that was launched with Memphis: “The success of Memphis shows that young people had been waiting for something like this, that there was a general need for better communication, a desire to escape from the cutting rules of the industry.” How do you keep these premises alive today at Memphis? Are they still valid or has production now overtaken all intrinsic meaning to become “mere” pieces of design history that people covet and collect?

Memphis has inevitably undergone an unstoppable process of historicization, which is what happens to the collections of all past great designers that are now reproduced by new companies, whether Charlotte Perriand, Pierre Jeanneret or Franco Albini. The difference in Memphis’s case is that we are not talking about re-editions or questionable antiquarian releases. The same company has continued to produce the same objects ever since they were designed and produced for the first time. And, I might add, those objects have never ceased to shock and scandalise.

A new website and new images from still-life photographers. This constant and renewed focus on communication seems to carry forward the original intent. Memphis is based around communication and while this, on the one hand, connotes the brand’s language, on the other it also drove constant reinvention up until the last collection in 1988, with ever new ideas and the involvement of countless designers. How do you go about bringing the “image” of these pieces, collections and photographs up to date when they are so firmly established in our collective imagination?

Every age expresses itself even when referencing the past. There will always be a new vision that offers a new interpretation of the same facts, especially when these facts have become legend.

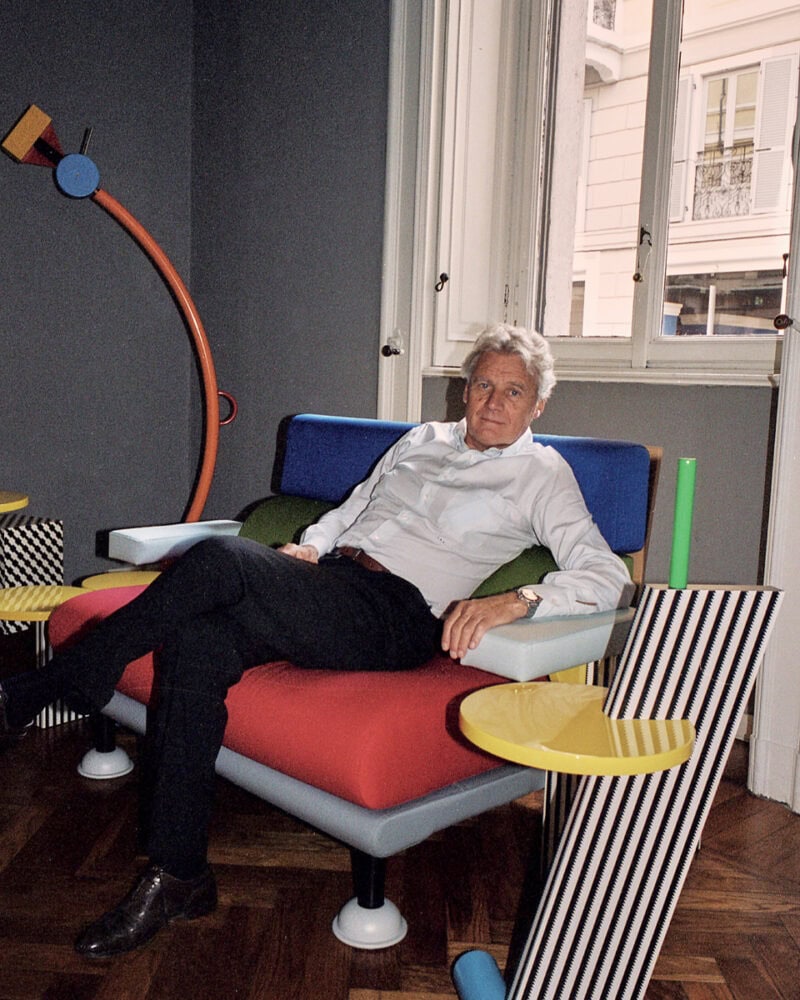

There is a strong relationship between object and space in Memphis pieces, how do they fit into the contemporary domestic landscape? What do they add? Do they establish new relationships or evoke those of the past?

Memphis pieces fit into any environment in the same way as a piece of ancient art or a Picasso precisely because they are iconic. It is always fun to find Memphis pieces in all sorts of completely unexpected settings, often in the last places we would have looked.

In your opinion, which of the great social and design transformations of today best tap into Memphis design?

The design world has never been as eclectic as it is today. Extreme minimalism exists alongside the most violent expressionism. Anything is possible in both fashion and design and perhaps it is this absence and coexistence of different directions that is the defining characteristic of our time. That is why Memphis is still so divisive today, loved and hated, current and obsolete: after all these years, Memphis still forces you to take sides, which is quite extraordinary.

Memphis knows no limits, whether industrial, disciplinary, decorative, or communicative. And it stands up under the weight of countless adjectives prefixed with “poly” to mean multiplicity: polychrome, polyhedral, polymorphous… How does this varied and disruptive idea of multiplicity fit into our current condition of hyper-connection, which seems to fragment rather than unite?

This world of multiplicity was widely predicted in Memphis design of the 1980s. What perhaps nobody could have predicted was the virtual dimension that would overtake the production and fruition of goods.

You are essentially a design “editor”. Who produces Memphis pieces? Do you still collaborate with any of the original contacts?

The producers of Memphis pieces in the 1980s, many of whom were extraordinary craftsmen, no longer exist. Companies have closed down or changing generations have inevitably led to a transformation in production strategies. However, all Memphis pieces are still made in Italy with techniques that have remained unchanged over time, and with the same passion and skill that has always defined Made in Italy craftwork.

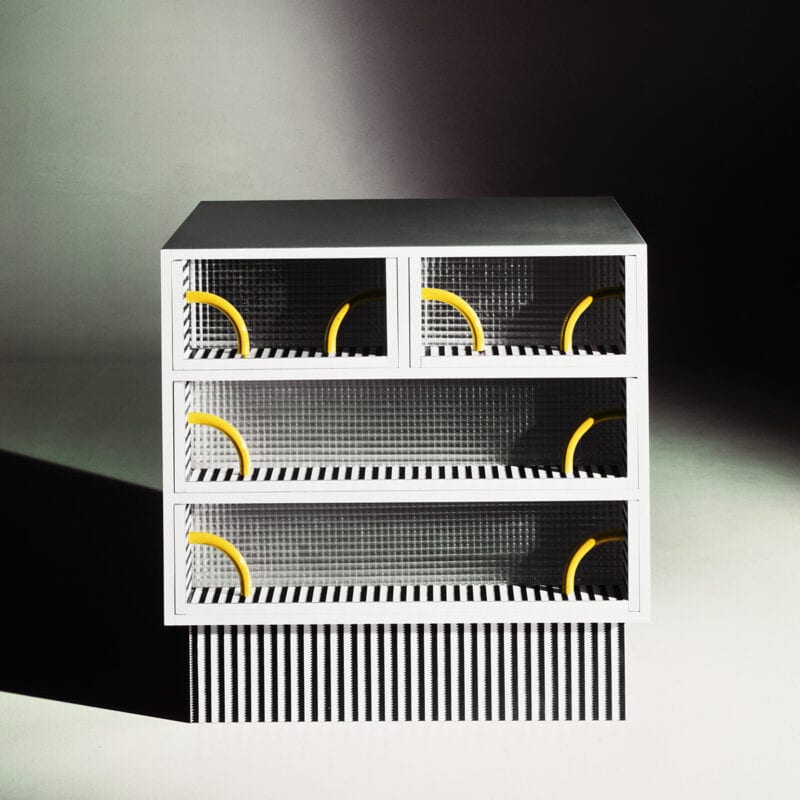

Wood, marble, ceramics, glass, textiles: a range of materials freely used and combined in defiance of the strict rules of pure functionalism. Laminates (from Abet Laminati), however, reign supreme here, with colours and graphic designs that were quite surprising for the time. It was an industrial experiment that is still very current. A material that has become increasingly ecological and versatile over time thanks to new printing processes. Memphis pieces have been widely copied but are they still unique in the innovative use of this material?

Memphis certainly played a role in this area although perhaps the reasons behind the laminate revolution lie more in aesthetics than ecology. In the 1980s, the bourgeois concept of the parlour-style living room with wooden furniture was still very much in vogue, so the use of plastic laminates in place of wood and marble, as well as abstract, pop, and colourful patterns, was a real slap in the face to the conformists. The expression “Épater le bourgeois”, coined by the French decadent poets of the 19th century, feels extremely relevant for 1980s Memphis.

Small-scale production, reinterpretation of artisanal tradition, sustainability, and Made in Italy: Memphis embodies all the elements which are currently in great demand in design at both a national and international level. Were Ettore Sottsass & co forward-thinking or is it a case of history confirming the value of the Memphis approach?

Sottsass had a prophetic vision that very few other designers and entrepreneurs shared.

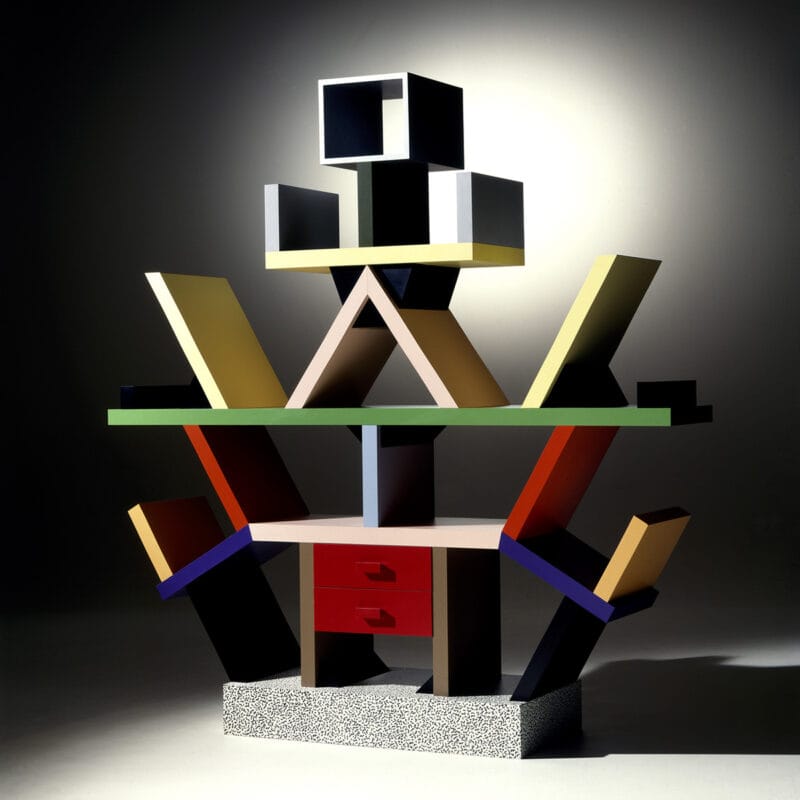

Other than the Carlton bookcase, the Casablanca cabinet and the Beverly wardrobe by Sottsass, which are among the most famous Memphis pieces (along with the boxing-ring bed by Masanori Umeda which marked his media debut), which pieces are most in-demand or have maintained continuous sales over the years?

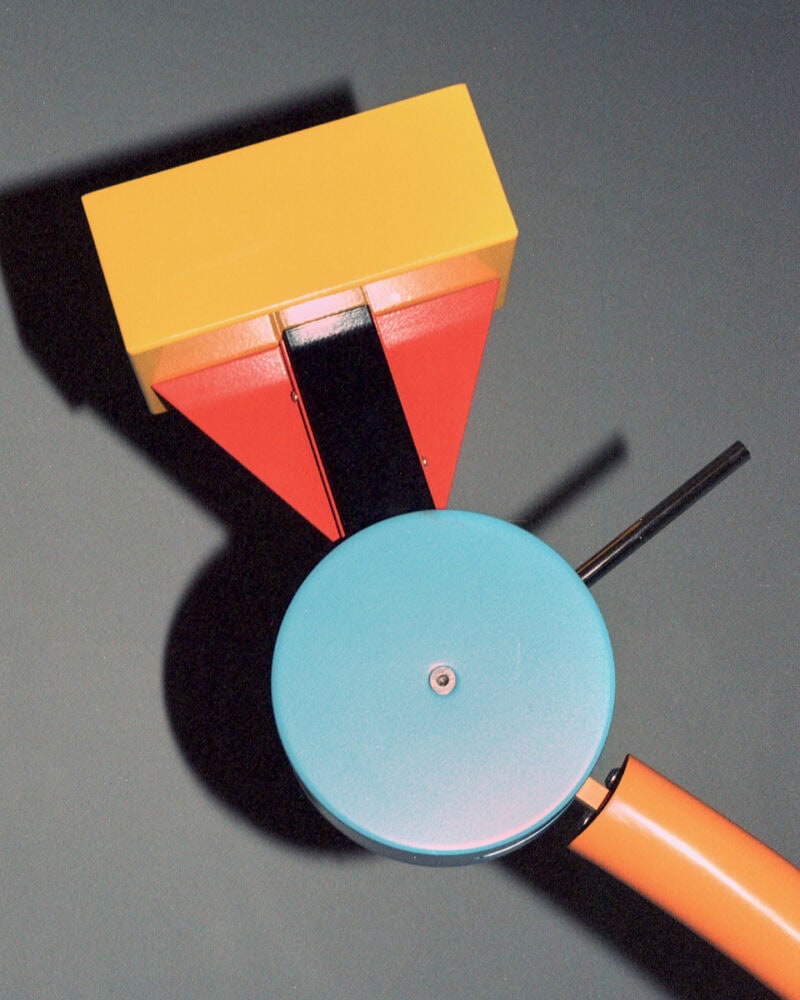

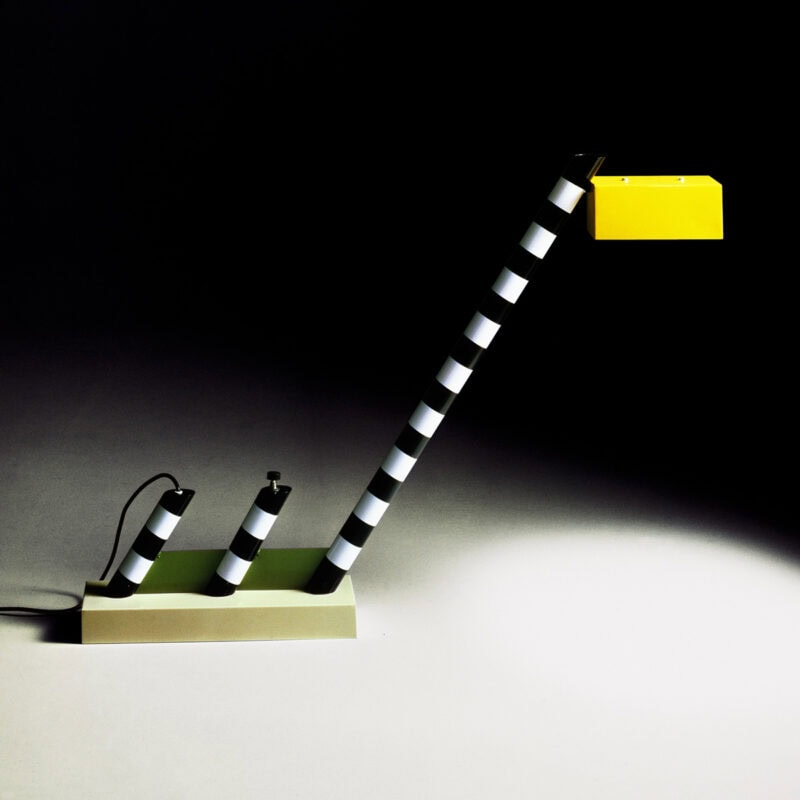

Carlton is without a doubt Memphis’s iconic piece per excellence and this is reflected in the sales, despite it being a larger piece, quite expensive and not easy to incorporate into the modern home. Some of our lamps are definitely extremely popular – Tahiti, Ashoka, and Bay by Sottsass, Super by Martine Bedin – as well as our glass pieces, almost all by Sottsass.

Another iconic feature of Memphis pieces and objects is how impeccably they are made. This also lends them a contemporary feel because it is as if they were made for sale via e-commerce. Touching them is less important than understanding them and appreciating their visual impact. What are your thoughts on this, given that the e-commerce represents a significant part of the brand investment?

It’s absolutely true. Memphis pieces are mostly purchased for their strong aesthetic by people who already know of them, so they do seem made for e-commerce. In the design field, Memphis was one of the very first companies to directly engage with the consumer through its own direct sales channel. People who buy Memphis pieces aren’t looking for a lamp or table to furnish their home with, they are looking for that specific lamp or that specific table because they already know about it and it appeals to their imagination.

It was 1996 when you embarked on what is both an exciting entrepreneurial adventure and an important role as cultural historian. What did Memphis mean to you at the time and how was it received by the market?

When I purchased the Memphis brand, its creative era had come to an end some 10 years earlier, the group had disbanded and, along with Sottsass, we decided not to produce any new products under the same brand. The decision, at the time illogical and uneconomic, proved to be correct since Memphis went on to become part of the universal collective heritage with a notoriety and prevalence that extends far beyond the lucky few with the means to purchase the products.

Looking back, would you do it all again?

Definitely, and with the same unconscious awareness I had at the time, which made it a cultural endeavour rather than commercial.

You knew and worked with Sottsass, not least on the logo for Post Design, your brand and contemporary design gallery. What are your memories of him?

I had the good fortune to meet Sottsass at various moments of his life. I like to remember him the way he was in his later years: a shaman with sweet, deep eyes, his long plait, and that expression of apparent indifference to worldly things that he shared with zen monks.

Post Design followed in the same vein as Memphis in terms of discovering unknown designers and creating innovative products. What is the common thread that connects your choices and what does it mean to be “innovative” in 2020?

The coherence of Post Design lies in its manifest incoherence. After two concluded ventures that were coherent in their own way, Memphis and Meta-Memphis, we decided that Post Design would simply be a critical observation of what was happening in the world of objects. This doesn’t stop us from making decisions, selecting some things, and excluding others, but it does allow us to develop a purposefully eclectic and multilingual catalogue.

What advice would you ask from Sottsass, if you could, in this strange moment of history?

Sottsass was a soothsayer, he had the power to intuit the cultural transformations taking place and translate them into objects. He wasn’t somebody that you asked advice of, he didn’t give it. It was enough merely to be close to him, to watch him out of the corner of your eye and await enlightenment.

Credits:

Words by Porzia Bergamasco

Photography by Carlo Banfi

Starring Memphis