A body can never be found wanting, it should never be assessed or packaged. Bodies are born alive and free, yet for some reason we learn to silence them and stay within the lines. Although they are increasingly the focus of social judgement and debates, we only think of them in terms of how they should look and what they should do, failing to ask the right questions. However, it is more than possible to re-appropriate our narrative and rediscover the value in being unique, which will in turn reveal diversity as the structural basis of a vibrant, balanced, and constantly evolving world. There will be different stages: from recognition of the system and how it affects and limits us, to discovery of privileges and discrimination and the uncovering of the toxic dynamics that we need to work on. It will be necessary to look at our culture and history, to actively shape our surroundings in view of our goals. We will have to recognise ourselves as unique individuals with rights and desires that must be protected, yet part of a system and of a community; and therefore we will have to unite and form networks, to support and inspire each other, because we are not islands. With this text, we can begin to walk that path together.

We all have a body. All bodies are unique and one-of-a-kind, and although we all perceive ourselves differently, there has always been debate about the “best” way to use our bodies. Our body can be a means for us to exist in the outside world, as well as a tool with which we represent our inner thoughts, emotions, and feelings. We use our body to present ourselves, show ourselves, and interact with the world. We can express ourselves, experience pleasure, be seen by others, and connect with everything around us.

But what does it mean to have a body? Or to be a body? How should a body be? Is there a standard model to be followed? Can a body go against nature? It is by asking questions that we start to look for answers but our hurried and hectic everyday lives mean that not many of us have the time, interest, or ability to further investigate what upon first glance may quite simply resemble a vehicle that we use to move, interact, and live. And yet, if we do not begin to question what surrounds us, what we think and what we think we are, there is a serious risk of getting lost in a struggle with our self-image. Especially if we forget that we are unique. Body image is the way that we all see and perceive ourselves. It not only has to do with what we believe about our appearance, but also how we feel about it, and how much we feel things physically and mentally. We all have a special relationship with our body. And yet, if we pay attention, we can identify patterns and similarities between the different ways we have of relating to and living with our bodies.

What does it mean to us? What is it like? How much is it worth? How do we look at it, or listen to it, or touch it, or judge it? Why?

These patterns are particularly common because our body image and the relationship we have with our body are deeply influenced and often built on the basis of the canons of beauty and attractiveness dictated by the society we live in. As individuals, we have always been attracted to the beauty of the human body, so much so that we seek it out, depict it, and celebrate it, but the perception of what is considered attractive has changed greatly throughout history.

Every society and culture have consolidated ideals that aim at perfection, a state of completeness that needs nothing more or less. Yet, and here philosophy comes to our aid, if the world – or a body – were perfect, it could not evolve and improve, and would therefore be lacking a key component of completeness: progress. Given its contradictory and seemingly illogical nature, the paradox of perfection in imperfection has struggled to find acceptance, despite containing the magic spell that might break the chain of chronic dissatisfaction with ourselves and our bodies. The concepts of sex and gender, and how they are perceived and defined, also derive from socio-cultural constructions. Between the eighteenth and twentieth century, Western societies firmly dictated and maintained a binary view of biological sex, which in turn influenced the consideration of gender and gender roles. Femininity and masculinity are concepts that have been defined over time on the basis of the characteristics culturally attributed to them, dictating the “rules” of performance for each gender which still apply and are often limiting. In recent years, these issues have regained importance and space in the debate. Among younger generations above all, there is an undeniable increase in personal and social interest and awareness, as evidenced by the recent and relative popularity of the non-binary vision ⎯ both in terms of sex , as intersex bodies show, and gender, something we have long seen in other cultures and which is now claiming a louder voice in our own.

The body that we have socially defined as male is often referred to as the standard, the starting point. Take the Vitruvian man, who was just the right amount of muscular and was supposed to embody noble perfection. Or the vision handed down to us from ancient times, whereby the feminine is an inferior derivative of the masculine. As the media constantly reminds us, the body associated with women has always been the most examined, judged, and objectified over time; nevertheless, there is no body that can escape the socio-cultural debate, albeit in different ways. It is as though, being the most obvious and concrete aspect of a person, the body can and should be passively subject to opinions, impositions, and evaluations.

One of the problems with ideals is that they are used as a yardstick for our own adequacy, and when they point to non-existent perfection it is clear that we will never be able to achieve even a minimum of satisfaction and complacency. Shame is what we feel when we move away from the model we aspire to be, or that we believe we should be.

“Acceptance does not mean passively enduring an image, it means not trying to demolish it at all costs in the name of a perfection that doesn’t exist.” (Valentina Tomirotti)

Today in Italy for example, if we leaf through magazines or turn on the TV, we will still often see the feminine represented with very specific beauty standards: pale skin, hairless and homogeneous women that resemble little girls, no fat, imperfections, or wrinkles, a thin waist but hips and breasts with “curves in the right places”, clear sensuality, long tapered legs, tall, but not taller than a man, and long well-groomed hair. Perhaps Barbie was the Vitruvian woman. Created as the doll that could be whatever she wanted to be and was supposed to embody a “strong and independent woman”, Barbie turned out to be an aesthetic yardstick for millions of girls and boys. And that wasn’t the only negative repercussion. It turned out that you couldn’t “be whatever you wanted” unless you too were beautiful, thin, and blessed with an infinite wardrobe. Now Barbie, or rather her manufacturers, have begun to understand the importance of introducing new models with different bodies. But cultural change is slow to evolve, and the classic Barbie-woman view has had a long time to take root.

This subversion of ideals was not kickstarted by a publicity stunt, of course, but by social movements that have spread so widely in recent years, thanks in part to the overwhelming power of the internet, that this topic has made it to the fashion and entertainment sectors.

At the foundation of Body Positivity is the Fat Liberation & Acceptance movement, which was started and carried forward by merit of black women and queer feminist subjectivity in the late ‘60s. Within the most marginalised segments of society, this intersection of discriminating factors is a driving force in the fight to reclaim the narrative around one’s own body. Where Fat Acceptance aims to deconstruct the culture of fat-shaming and discrimination on the basis of size or weight, Body Positivity focuses on the struggle for the socio-cultural normalisation of all bodies, insisting on everybody’s right to have a positive perception of their body free from external impositions because ⎯ and this is the important part ⎯ there is no right way to be.

Contrary to the extremely simplistic and unrealistic messages that mainstream dissemination of this concept tends to transmit – that is, to “love ourselves the way we are” – the body positivity movement teaches that society is responsible for recognising the normality and value of all bodies, transforming phobic and discriminatory habits into inclusive approaches that celebrate the uniqueness of each and every one of us. This is because, as people with non-conforming bodies know particularly well, the path to self-acceptance and feeling good in one’s body is extremely difficult to walk when there is still so much external hatred and hostility.

That is why the movement’s initial goal was to challenge unrealistic female beauty standards. But all struggles evolve, and time and increased interest predominantly caused by the circulation of the #bodypositivity hashtag (created by and for people with marginalised bodies) has brought this topic into popular debate. The evolving focus has taken two directions that appear similar but are conceptually very different: there are those who associate the movement with the message “all bodies are beautiful”, and aim to expand our idea of beauty and include people of all gender identities, ethnicities, sizes, ages and abilities; and those who subscribe to the idea that “all bodies are valid and deserve respect, love, and representation”, which overcomes the very concept of beauty as a value and creates space for dialogue about our rights, and self-determination first and foremost.

We talk about self-determination today thanks to feminisms, since this right has been made a key point in the fight to claim total autonomy over our bodies and image, opposing the various forms of systematic violence, coercion, and discrimination suffered by the female gender and by all non-normative and minority subjectivities. “My body, my decision” is not merely a slogan, but the voice of a movement of people taking back the freedom that has all too often been denied them.

“Our body is not a public garden that we must keep mowed and ornamented for the enjoyment of all: our body belongs to us alone.”

(Giulia Blasi)

We are not free when subjugated to standardisation, nor when controlled by standards of acceptability and beauty, which exploit the dissatisfaction they generate. Yet we might spend our entire lives oblivious to this because sometimes it is easier not to ask questions, to avoid doing the work, and just stick to what is “normal”, or what they tell us is normal. They made us believe that our worth is based on our productivity and beauty, that we require the approval of others and that we are lazy, wrong and uncaring if we don’t strive to be better and better ⎯ according to certain very precise criteria. We give unsolicited advice to friends and strangers, we constantly comment on other people’s bodies (often before anything else), we try to exploit health when it suits, forgetting that any decisions concerning the body belong solely to the person who inhabits it and that, at times, there may be no choice or it may be far more complicated than you can imagine. We spend our lives chasing a normality that doesn’t suit us, forgetting that the only normality that matters is our own. We want to be like other people because the fear of being different is closely related to the fear of being alone and unwanted. They teach us that everything is simple, binary, and natural ⎯ and that we should avoid, judge, and even hate everything else.

Within this system, body shaming is a false bargaining chip: we think that we will gain power and self-esteem by labelling, insulting, and belittling other people’s bodies, when in reality we feed into a vicious circle of hatred and shame that we ourselves are not immune to. As my grandfather used to say, “every time you point a finger at someone, other fingers are pointing at you”. On some occasions, this means that judging others negatively is probably the reflection of a toxic habit that we turn onto ourselves every day; on others, it teaches us to recognise that everyone is fighting internal battles that we are unaware of, and that giving offering opinions is not only harmful but also unjustified. My body, my decision. Nonetheless, body shaming enjoys constant growth, and is perpetrated by and aimed at people of all genders, ages, and social backgrounds. While it is explicitly women and minorities that are most affected, it is also very common for the male body to be “shamed”. Little attention is paid to this phenomenon for several reasons: on the one hand, commenting on other people’s bodies is generally such a normalised toxic habit that it goes almost unnoticed ⎯ “Where are your muscles?”, “You’re too short”, “You’re getting chubby, why don’t you hit the gym?”, “I hope he doesn’t have a small penis” ⎯; on the other, because the men who are victims of these comments struggle to talk about it, due to stigma, the inability to recognise these dynamics as wrong and offensive, and a lack of real listening and understanding from the outside.

Once again, it is gender roles that provide our reference points when engaging in this type of psychological violence: they tell us what “real men” and “real women” should be like, establishing what we should point the finger at, what the defects are, what needs to be improved, and just how much we are lacking in order to be appreciated, welcomed, and accepted. We all have bodies, so this is something that affects us all. Nonetheless, there are people who manage to shut their eyes to their privilege in the face of the injustice and discrimination that less “fortunate” bodies usually experience. There are many levels and intersecting areas that build our identity and, in the same way that privilege can pile up, so too can discriminating factors, almost like points in a game, only in this case, the more you have, the bigger your loss.

When we talk about the bodies that aren’t “accepted”, we think almost exclusively of non-standard sizes, such as the fat, obese, and infinifat bodies that suffer intense pressure, micro-aggressions and continuous psychological violence from a decidedly fat-phobic (does not accept, discriminates and rejects anything “fat”) cultural mould, but the list is far longer. In addition to the other extreme, this affects the bodies that are considered “too thin”, the trans bodies, whether transitioned or not, the androgynous, non-binary bodies that are not exclusively male or female, such as intersex bodies. It affects bodies with dark skin or non-Caucasians, still plagued by prejudices and “fear of the other”. It affects people with disabilities, whether visible or invisible, those who aren’t self-sufficient, or limited by architectural, as well as social, barriers. Then there are all the bodies that, to the people who live in them, have plenty of defects: too many wrinkles, white hair (yes, even age is a discriminating factor), too much or too little hair or body hair, too many or too few muscles, this kind of feature instead of that, the “wrong” curves, one thing too big and another too small. No one can ever pass this corrupt exam, and this realisation is the beginning. Like every person I have ever met, I too have had a complex relationship with my body and the idea I had of myself. My personal experience has gone through extreme highs and lows, and periods in between where I was able to look at myself contextually, as part of a system and not just “a body”. There was the moment when I deeply hated my body and another when I forgave it. I began to observe myself in all different situations and I learned to recognise the toxic dynamics that I had absorbed ⎯ such as habitually checking my body, to make sure I was “okay” and attractive at all times, or self-objectification, where I valued my body as an instrument solely for the pleasure of others. The deeper my relationship with my body, the more I learn about myself and the world. Starting from recognition of my privilege ⎯ having a white, healthy, able body of a size deemed “acceptable” ⎯, I work and educate myself every day on how to exploit that privilege to dismantle inequalities and celebrate differences, giving space, voice, and recognition to those who have less than me.

I have used my body to express myself, to get closer to others, and to get to know myself. In fact, I would never have developed any of these thoughts and reflections had I not had the opportunity to expand on my own individual need, which was to really open up conversation around these issues -with a new, necessary, collective – and also rather urgent – approach. This was the beginning of Virgin & Martyr, a project with multiple voices and bodies, which started life as a photographic archive to honour of the uniqueness of bodies and evolved into an all-round media platform. Rather than seeking static and simplistic answers, we seek to spread information, new perspectives, and the chance to formulate your own personal opinions about everything and anything that concerns the body: from pleasure and emotions to communication and identity ⎯ free from stereotypes, taboo, and prejudice. Our large Instagram community has always been active within the revolution that is also taking shape across Italy. In our own small way, we want to contribute to a new culture that is more positive about bodies and sexuality, but also more inclusive and accessible, a culture that leaves nobody behind and, on the contrary, supports those whose struggles are greater. That is why we focus on increasing awareness online and offline, on a school curriculum that does not impose an equal vision on everyone, and on the training of young people and adults to create safe places in which to discuss these issues. This now highly focused mission was developed through our daily interaction with the tens of thousands of people who follow and support our work, with their experiences, thoughts, and desires.

“I want us to move towards more honest conversations about our relationships with our bodies and how we exist in this world. What is the point of talking about all of this if we don’t tell the unadulterated truth about our experiences? Who does that benefit? Certainly not us.” (Sherronda J. Brown)

In these three years of activism, I have certainly witnessed changes on a social level, even if only by comparing all the initial messages requesting help and a kind ear with the many messages of thanks received from people who, alongside us, have become more aware of themselves, of socio-cultural mechanisms, and of the tools at their disposal to improve things. I am perfectly aware of the fact that outside the Virgin & Martyr “bubble”, the world ⎯ or Italy in this case ⎯ still has a long way to go before we can talk about cultural change, also because by definition, shaping a culture takes time as well as active engagement. There is no shortage of good intentions but there is also no doubt that it is far easier to indulge in blissful ignorance, keep quiet about these issues, and leave things as they are. Yet, the “not a problem until it’s my problem” mentality by its very nature means that there won’t be anybody to help us when we are the victims, although this “self-preservation” shouldn’t be our only motivation for getting involved in the struggle for human rights.

There are many people who blindly follow, feed, and venerate traditional aesthetic canons, who claim the right to comment, judge, and decide for the bodies of others, and who contribute to this environment of intolerance, division and segregation but, I assure you, there are just as many who want to change all this and are putting all their effort into it. Each and every one of us can do our part, because it involves all of society’s roles: from activists to employees, from students to researchers and teachers, not to mention artists, doctors, journalists and bar staff ⎯ because our culture is made up of all of us.

Many new projects, associations, and organisations with different forms and constitutions have been set up throughout Italy in recent years, focusing on the various different branches of the struggle, such as Belle Di Faccia, which stands against fat-shaming and fat-phobia; Info Trans, the government portal dedicated to trans people; Uno Collective, an artistic anti-racist collective for change; Witty Wheels, a duo of activists fighting for the rights of people with disabilities; and Le Spettinate, which campaigns for sex worker’s rights. Not to mention those that have been active in this sector for years and continue to contribute to change, such as Arcigay, Tlon, Bossy, Body Positive CatWalk, Razzismo Brutta Storia.

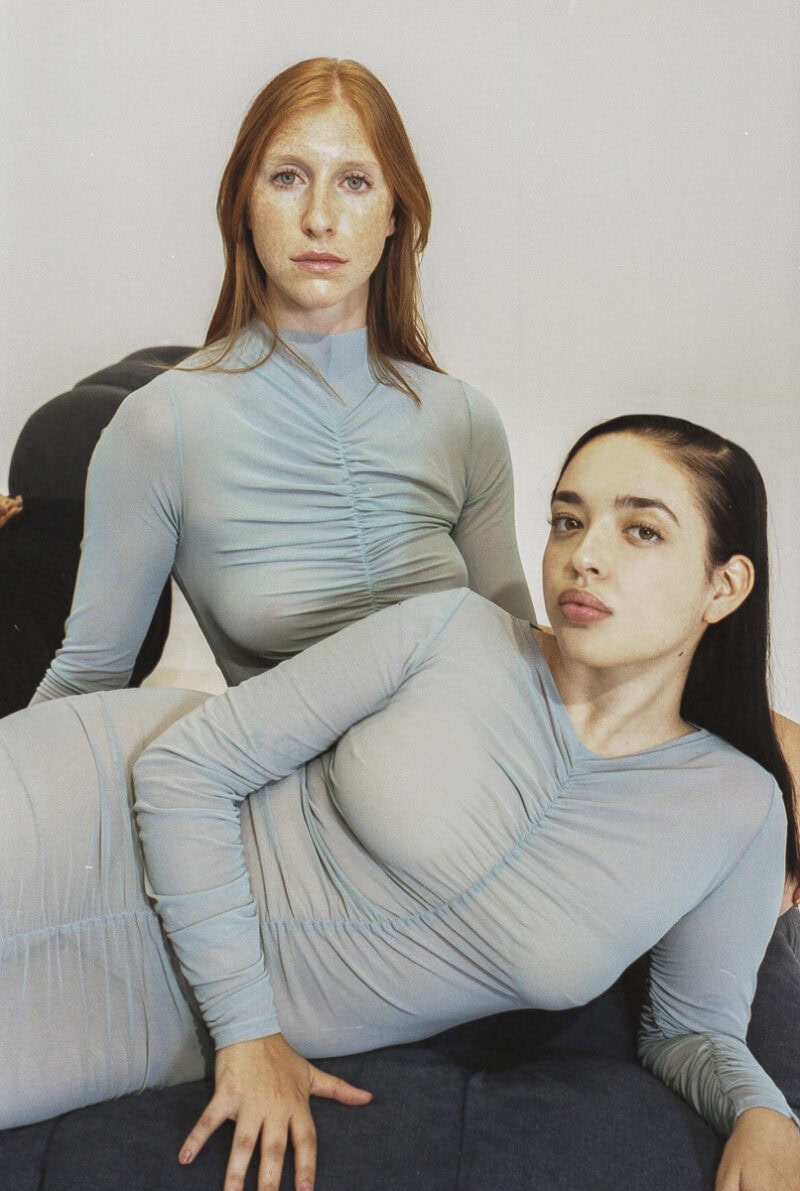

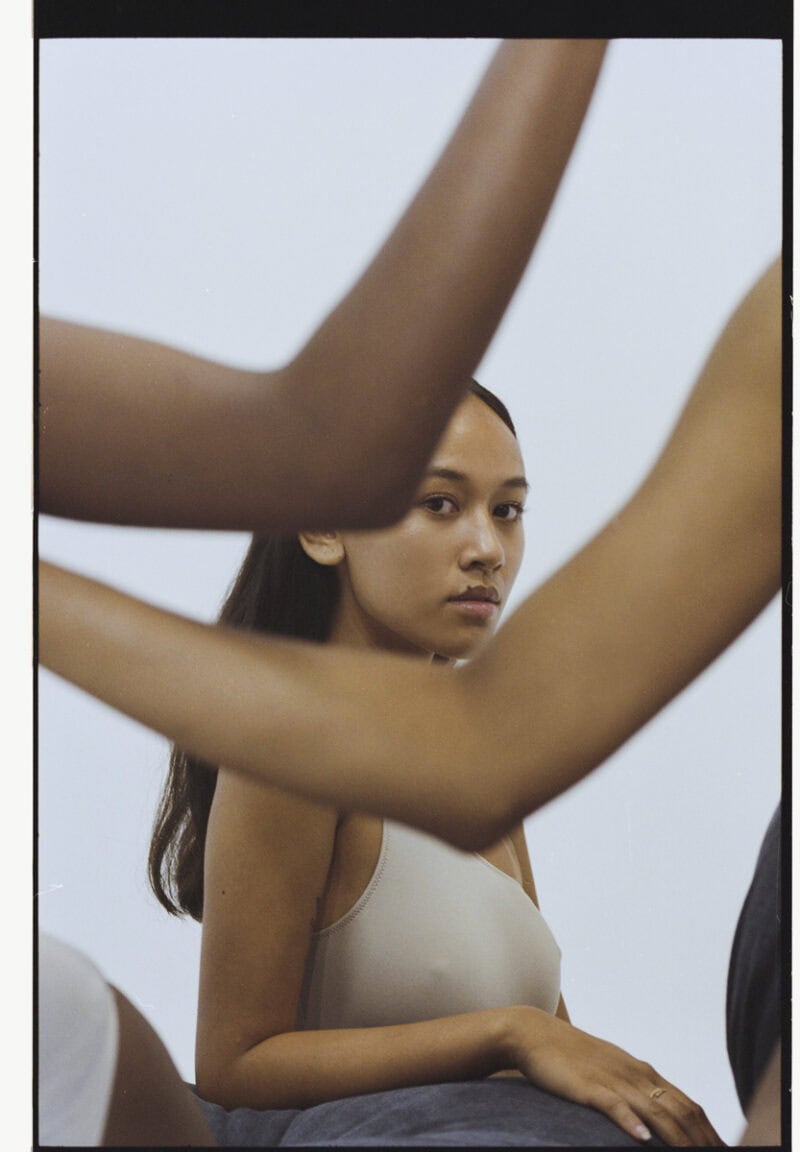

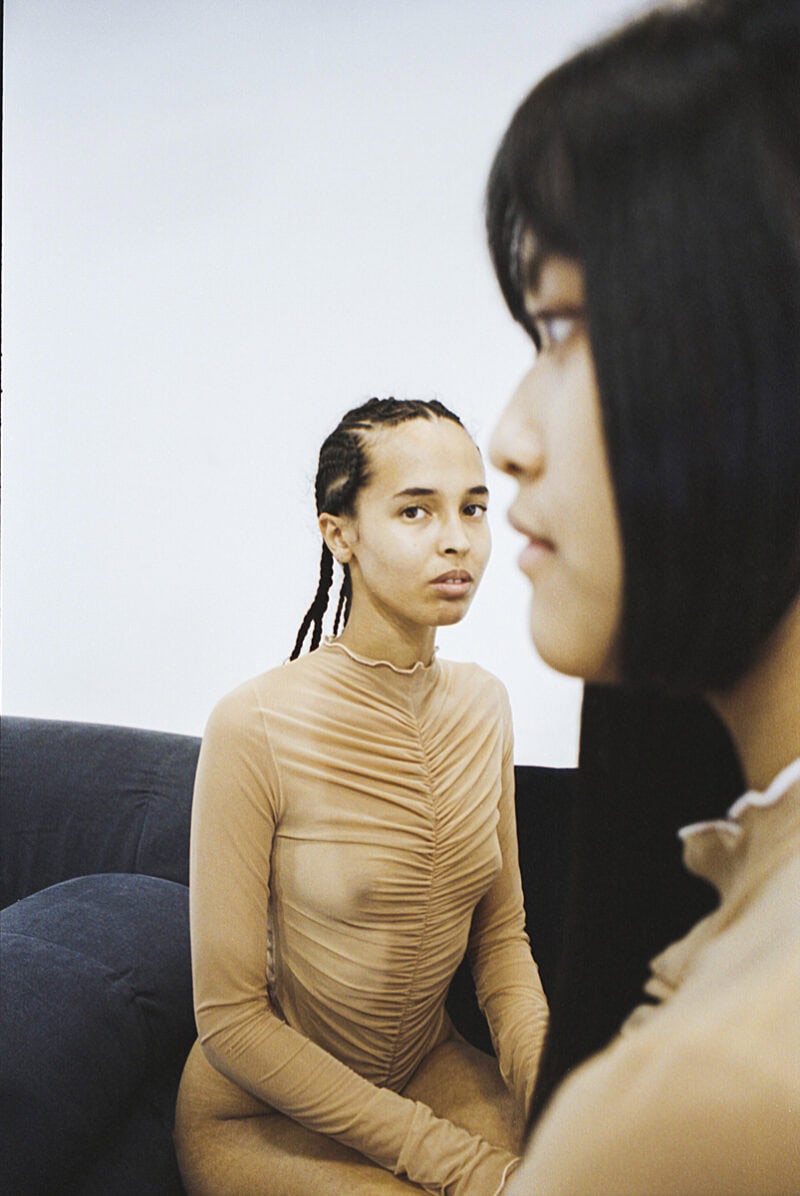

In particular, anybody running a brand or agency, or working in advertising, entertainment, or general media representation, has the opportunity and the responsibility to introduce the values of change into their work and provide visibility and recognition to all bodies, as we have already seen in Italy from companies such as Fantabody, the independent brand from Carolina Amoretti that puts Body Positivity, the celebration of uniqueness, and encouragement to believe in oneself at the core of its values. Even more traditional fashion houses such as Gucci and Prada have realised, having been embroiled in various controversies, that Inclusivity and Diversity are fundamental values that can no longer be ignored. Be careful however that your movement for social change is not a mere marketing strategy. There is no need for messages such as “have the courage to show yourself the way you are” or that “feeling beautiful starts from you”, because it is the idea that no body needs approval to exist that we need to permeate our culture.

The endless path towards self-love and self-confidence starts from gaining awareness about what influences our relationship with ourselves, and how.

They are qualities that make us our very own best friends, capable of wanting the best for ourselves, and knowing how to listen and take care of ourselves without judgement. If loving oneself is an act of rebellion in a system that derives its power from making us feel wrong and dissatisfied, nurturing one’s self-esteem prepares us to face the world, and to fight to make it better.

Things are changing because we want to change them: true and pure intention is in fact the driving force that shifts things toward the direction we have chosen. Many good intentions have enormous power which, combined with conscience, unconditional mutual support, and time, can reshape the structure of this fallacious system which is increasingly revealing itself as an old imposition that no longer reflects us and merely holds us back.

It is said that we won’t see a cultural upheaval or a society in which toxic concepts and beliefs have finally been eradicated in favour of values that understand community as a gift to be protected. It is said that we will have to wait for generations in order to witness a real overturning of the system in favour of humans and their precious uniqueness. While this may be true on the one hand, on the other, it may not be a cause for discouragement: not only are we witnessing and actively participating in a revolution, but at the same time we are working on the relationship we have with ourselves and with others, consequently improving our internal and external environment. Even the most subtle changes can have a great impact on our lives and being the ones to put them into action is both a privilege, a talent, and a choice.

Credits:

Words by Greta Tosoni

Photography by Carolina Amoretti

Photo Assistant: Virginia Guiotto

Fantabody Team: Sofia Atzori, Anna D’Aprelà

Camaleonda, modular sofa, designer by Mario Bellini for B&B Italia