Daniel de Paula is an artist and researcher born in Boston, and currently based between São Paulo and Amsterdam. His work focuses on how space reflects power dynamics, bringing attention to the political, social, economic, historical, and bureaucratic structures that influence contemporary environments and relationships. Beyond visual arts, de Paula’s practice and production intersect with geography, geology, architecture, and urbanism. This highlights his unique understanding of the complex social forms embedded within materiality. He employs various strategies, such as extensive negotiation with public and private agencies, appropriation and displacement of everyday objects, and decontextualisation.

Ilaria Sponda: What’s in your head at this time? Any particular project you’re working on?

Daniel de Paula: At this very moment I’m installing new work in the context of the Luleåbiennalen, in Scandinavia, in the extreme North of Sweden, inside the Arctic Circle. I’m in a city called Kiruna, a historical mining city, in the region of Norrbotten. It has the biggest iron ore mine in the world, named LKAB, from which 90% of the steel utilised in Europe originates. Rare earth minerals have also been discovered in the region. The expansion of the mine is displacing the city, since the extraction process is advancing underneath the inhabited area, and if nothing were to be done the city would collapse, so they are moving the entire city some kilometres away. Demolishing, dismantling, rebuilding, reassembling etc. The work I am producing itself is a permanent public sculpture, small in scale, yet ample in subject matter and material histories. It will intervene upon the ongoing reconstruction of the city, and will somehow slip into, and place itself, both physically and temporarily, into the reality of the new urban context that is being built, it will become, even if subtly, a part of the city. Even though the Luleåbiennalen opening is in early March, the work will only be installed at the end of the exhibition, late May, due to weather conditions of the location, since, currently, the floor in Kiruna is completely frozen. Besides this specific public work, I am also participating with some other works inside an institutional space.

IS: What appeals to you about this mining city? How does this converge into your artistic practice?

DDP: There are several converging social and political vectors unfolding here, which are quite complex, especially since they take place upon indigenous land of the Sámi people, where, not only the mining activities, but also infrastructural work in general, has violently impacted human and non-human life tremendously for over a century. From hydroelectric dams to data-centres, railway systems to an international space station, this region is quite fascinating and dynamic. It’s a geographical territory that is in a constant space-producing flux, determined by both state and private interests, local and global, and that can, when critically investigated, be an important study case for grasping what are the historical, political, economic, and social forces at play in our world. What is it that, more than being shaped by space, shapes space itself? Moreover, something that interests me as well, and that specifically informs my work, is to consider how certain particularities of a place are able to reveal global processes and point towards an idea of totality, speaking about dynamics that are occurring simultaneously across very distinct places in the world. Therefore something that is very specific to a location can actually illustrate a more universal occurrence. I’m talking about violent forces that are also at play in other places in the world, abstract ideologies, such as capital, property, labour, and value, that produce space and determine our lives.

IS: The production of space is something that has driven human activity for thousands of years. How does this topic matter to you?

DDP: I am indeed interested in the production of space, in a critical manner. The city of Kiruna is being, as mentioned before, demolished and dismantled, reconstructed and reassembled, and such process, quite unique and exceptional, is happening in an accelerated and planned-out way, where motivations and decisions become more visible and graspable, and, consequently, allow for an in-depth analysis to take place, a probing into the way space is produced. One has to comprehend that the physical space around us is not neutral. It’s an extension of an ideological process, a process that aims at maintaining our modern capitalist economic structure, where the production of value, the production and exchange of commodities, the mobility of labour forces, the extraction of natural resources etc. is not questioned, but on the contrary, is seen as natural, as the only way to produce space, as the only way to live, our only option. Building a city is not a neutral act, it is a charged act, and as a society, we have chosen to produce space in conservative ways, rather than imagining new forms of existence, emancipated from all our current social burdens that result from our capitalist sociability. There’s a particular ideology embedded in the physical material reality of space, the way we produce space is the way we live in it and vice-versa.

IS: What artistic object are you going to place in the city of Kiruna?

DDP: While thinking about the local context, and themes related to extraction, labour, death, rebirth etc. I proposed a piece titled combustion / production, a new site-specific artwork developed specifically for the town of Kiruna, and it consists of a pavement stone composed of three distinct metals, melted and fused together. A fraction of the metal is coming from the world’s largest iron ore mine in Kiruna, operated by LKAB, a Swedish state-owned mining company. The other metal comes from the clock pointers, or clock hands, of the famous public clock tower of Kiruna’s first City Hall, which has now been displaced and installed in the town’s new city centre. The third material is recovered metal from the process of cremation of corpses in Swedish crematoriums, recuperated and recycled by companies that reintroduce them in market circulation, generating profits that are directed to the Swedish pension system. The three different metals will be melted and cast into a pavement stone that will be installed in Kiruna’s public space during the closing of the Luleåbiennalen and inhabit the new city centre for posterity. It’s a complex work, materially, both in the provenance of the materials and the negotiation processes required to obtain the materials, as well as technically challenging, production wise, having to deal with distinct metals with varying melting points. Furthermore, placing the object, with municipal authorisation, into public space, also required further negotiations.

IS: Can a decontextualised object be read simply as bare materiality, purely as nature?

DDP: Materiality is a way to read the world. Materiality isn’t neutral, it’s embedded with certain abstract ideologies, it hosts ghosts, things we don’t see on the surface. We don’t relate to them as bare nature, since well, we relate to them, through us, and we carry projections, intentions, ideologies etc. With materials we produce the physical space around us, we produce it in order to fulfil our human necessities, and in our modern capitalist society our necessities have unfortunately been reduced, mostly, to the production and exchange of commodities. So our surroundings aren’t simply natural materials, pure minerals for example, neutral in their existence, but they are nature processed through labour, transformed into commodities, and that are exchanged for money and utilised to erect our capitalist infrastructure, an infrastructure that has an interest in perpetuating this way of existing on this world. We work, extract, produce, and exchange, all in order to keep working, extracting, producing, and exchanging, so a port, a house, a highway, a dam, a wind turbine, a mine, a shopping mall, they all play a similar role in the construction of a place where a certain sociability might unfold, where property, labour, value, and capital can keep inhabiting, possessing things. More specifically, in the case of Kiruna, metal isn’t simply metal, pure iron ore, it is a force capable of demolishing and rebuilding a city, and all that such process entails on an emotional and social level.

IS: Within your practice, what does the process of negotiation entail? How is it relevant to your creative process?

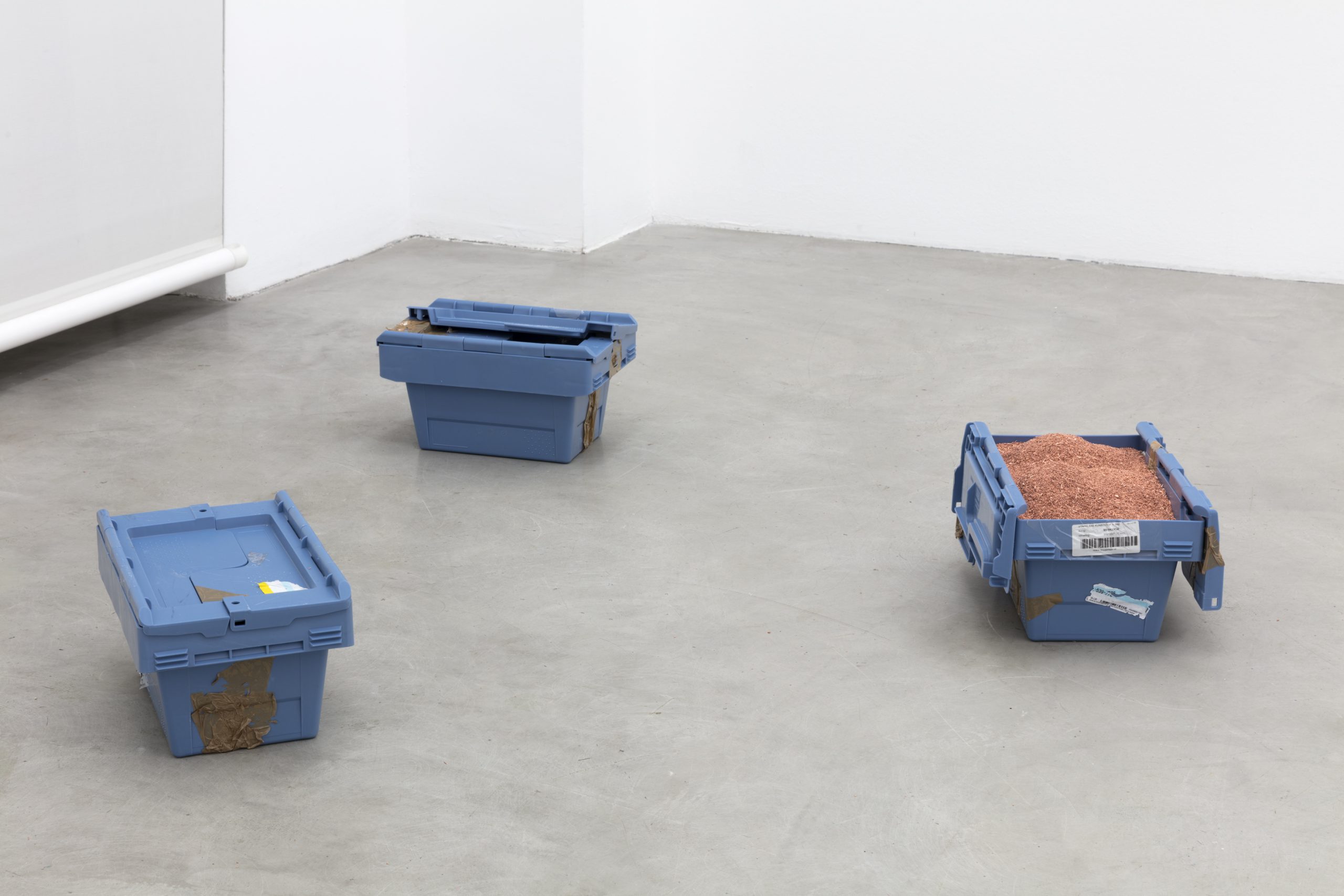

DDP: The process of locating the specific socially, politically, and historically charged materials and objects I make use of, as well as obtaining them, usually without cost, is foundational within my practice, as well as extensive conversations and discussions with agents that constitute the institutional spaces, be them public or private, in which my work is placed and presented. I call such a process negotiation. I consider it not only part of the process of the work but a component of the work itself, a component of the material list of the work, one could say, reiterating the fact that actions produce space, impact objects, and inform the physical world around us. Therefore, these negotiations inscribe further layers of meaning into these already charged objects and places. Fundamentally, it might be an attempt to rid oneself of more formal and physiocratic relations to the space around us, and to artworks as well, grasping the fact that a social form is concealed with materiality, that all the space around us is a consequence of a multitude of daily negotiations. I think it is important to highlight that aspect of the work, it’s not simply a list of physical things, such physical things are all informed by actions, some visible, some invisible, some close, some far.

IS: Is there any object that you feel is capable of unveiling the existing power dynamics at play in our society? The power dynamics that dominate and subject our lives?

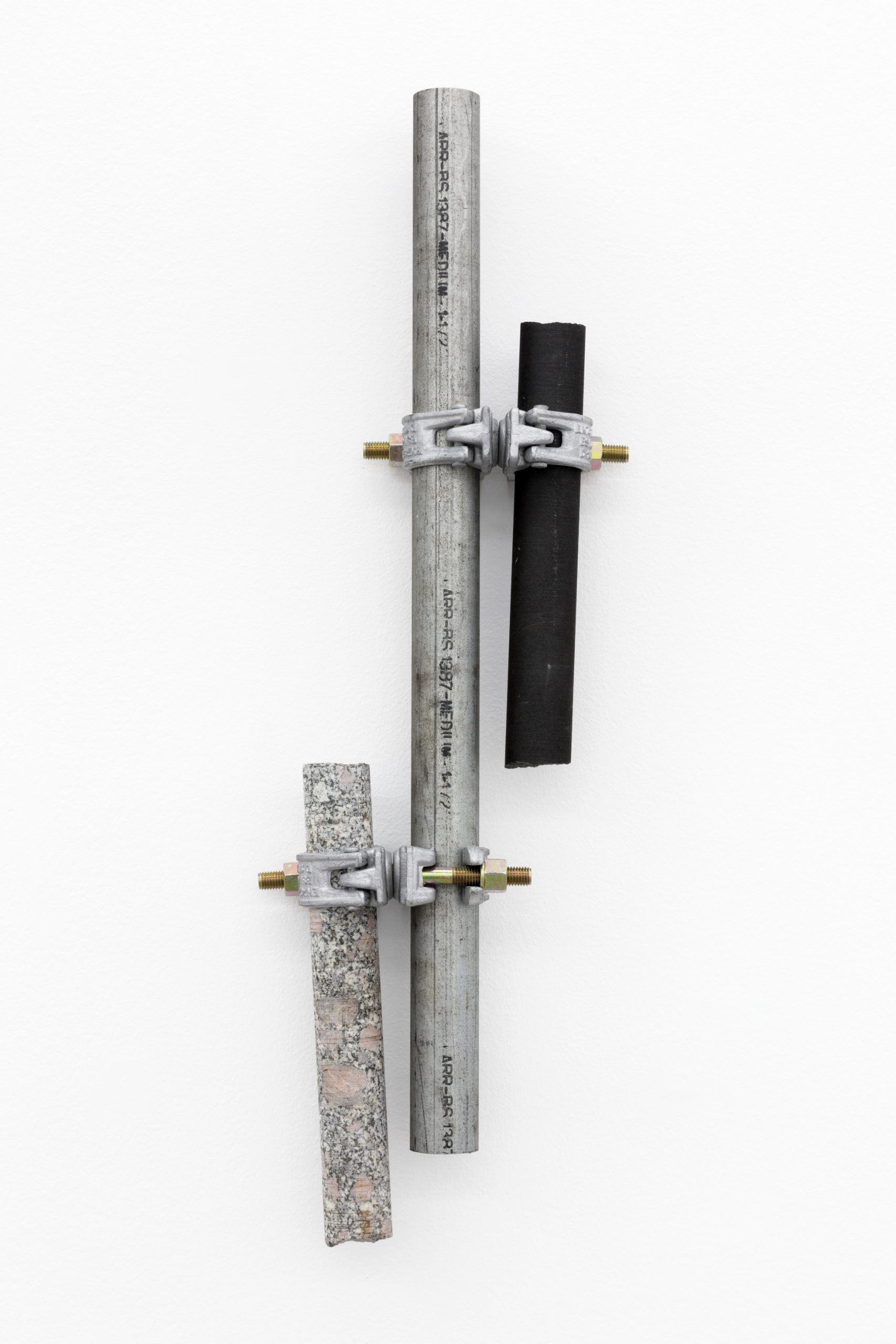

DDP: Not only throughout my career but in specific exhibitions themselves there’s usually a wide range of materials I gravitate towards. They are in almost all circumstances objects and materials that are existing in the world and that carry with them some latent historical, social, or political force within them. Rather than focusing on a particular formal aspect of the object I am interested in the contexts from which they arrive, what I mean is that somehow the context reveals the object, and not the other way around. I’m not interested in objects because of their formal qualities, but because they can speak about a context more precisely. In the end, I think the variety of the objects showcased actually produces further evidence of certain common denominator dynamics that occur throughout the world. Yet if I had to highlight one kind of material or object that I believe is capable of unveiling the mechanisms at play in how we produce space in our society, it would be infrastructural objects, which are quite diverse in their shape and form and scale, but share similar uses.

IS: Is there anything that cannot be sold or commodified?

DDP: I don’t believe so. Capitalism is quite radical and revolutionary when it comes to the capacity of inventing new forms of commodification. One might accept it or not, but there are quite some contact areas between inventive capitalist strategies, mostly in the realm of finance, and conceptual art, both deal with abstractions, ideas translated into systems of belief, the creation of objects of translation and an interest in the reception of ideas by a broader audience. A particular example of how all can be commodified, and which I have highlighted in a particular work of mine, is the fact that I’ve been extensively working with shadows, selling them to collectors and exhibiting them, in an attempt to shine light upon the fact that property and proprietorship are not a natural given phenomena, but a socially constructed ideology, founded on legal systems and so forth. In the context of a solo exhibition at a commercial gallery in Brussels, in 2021, I displayed an industrial object, part of the collection of a museum in the Netherlands, and which had been in use in a ceramic factory in the 1800s, and where, as one might suspect, labour rights weren’t a thing. It has been speculated that Karl Marx made a visit to that factory, since his sister lived in that town, and such visit occurred prior to his publishing of Das Kapital, therefore he might have been in the vicinity of that artefact. My interest in displaying the object was actually in exhibiting the shadow it projected, both physically in the space, but also thinking of it metaphorically, contemplating the shadow as an abstract category such as capital, property, labour, and value. These concepts and ideologies are shadow-like, fantastic fantasmagorias that dominate our lives, yet aren’t real physical things, they are not in the object, but are concealed by it. Eventually I placed the shadow of the work for sale, and once the exhibition was over and the object went back to the museum, a collector purchased the shadow and simply received a certificate of authenticity, as well as sales documents confirming his ownership of the shadow. The requirement to own an object is not always an imperative to have the possession of a physical thing. Later on, I also placed my own shadow, the shadow of my gallerists, and of mountains pertaining to the history of neoliberalism, for sale.

IS: Isn’t there any ethic implied in the selling of a shadow?

DDP: As an artist that’s contemplating power relations as well as my own role in the art world, producing commodities like anyone else, I question my ethical boundaries, but don’t romanticise them. I question ideological systems that have been naturalised within us. Is selling one’s shadow something anti-ethical? Is it any different from selling the time of our lives through labour? We are the ones that project value upon nature and time by means of the concepts of property and labour, therefore, if we are capable of producing value through our sweat, will, and our own determination, why wouldn’t we be able to do that same with a shadow? It’s framed as an artwork, a fruit of my labour, of the accumulation of hours I spent devising such an idea and executing it contractually. All is commodified in the capitalist world we live in. The financial world is an obvious example, as it is a duplicate of the “real world.” Stocks aren’t physical products. With that being said, if someone is interested in creating a market for the exchange of shadows, producing value, speculating upon them and so forth, it’s as unethical as finance and trading. Hopefully, such procedure can trigger reflection regarding what we’ve naturalised in our society, selling one’s time, selling one’s life one could say, in order to pay the bills and live, most in a precarious manner, that, I would argue, is much more unethical than selling one’s shadow.