Erris Huigens’ work represents a contemporary practice of public art-making and space rethinking practices. Rooted in an ethos guided by the frictions between minimalism and graffiti art, his work resides at the intersection of street art and in-studio work. In this dialogue, Huigens—also known as Deconstructie—reflects on the industrial sites he privileges for his paintings and his polyvalent relationship to them. He delves into his understanding of the agency of minimal art today; his approach to real-life art and its photographic reproduction and virtual circulation; and ideas around deconstruction.

Ilaria Sponda: I’d like to start by talking about your recent work in the Netherlands and your studio practice, because I think it expresses something fundamental about your work.

Erris Huigens: I recently moved from Amsterdam to a more rural city next to the river Rhine. I’m surrounded by a lot of industrial places. I’ve moved away like many artists to stay with the rough edges, which in major cityscapes are fading. It’s overall a natural cycle, as money takes over everywhere. I have a lot of things going on—it’s not a surprise to hear, I guess, as this is what artists usually say. My different projects are happening simultaneously: I divide myself between studio time, open-air experiments in the industrial sites around where I live, shows and research. I’m now at a point where I’ve done a lot of research and loose projects that I feel like I want to come up with some sort of resolution. I’m maybe in the process of becoming more of a ‘classic studio painter’. What I know is that I just don’t want to paint nice paintings. That’s never been my aim. I feel like I’m starting all over again after a long time of thinking and writing; it’s now time to act.

IS: How would you describe your practice?

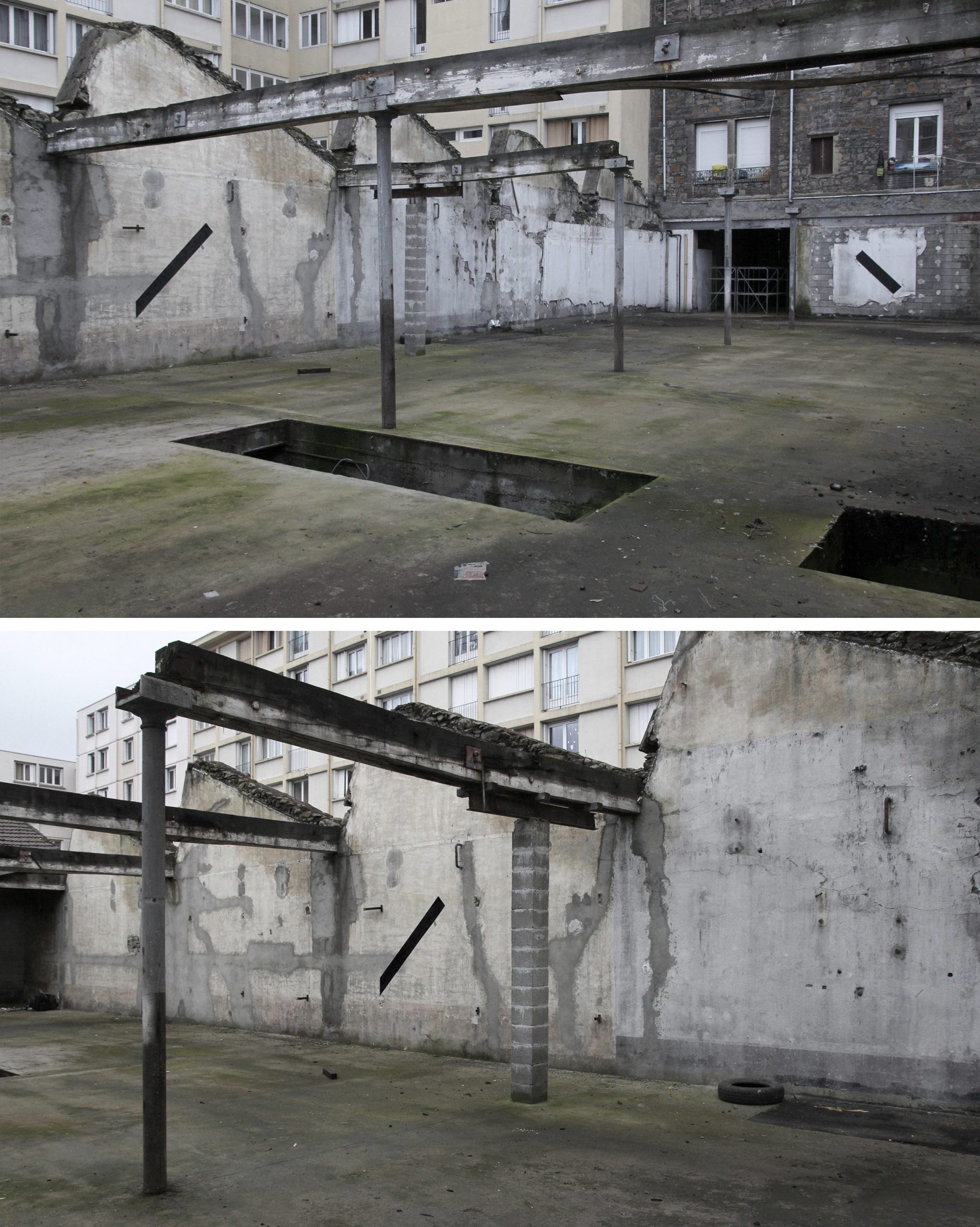

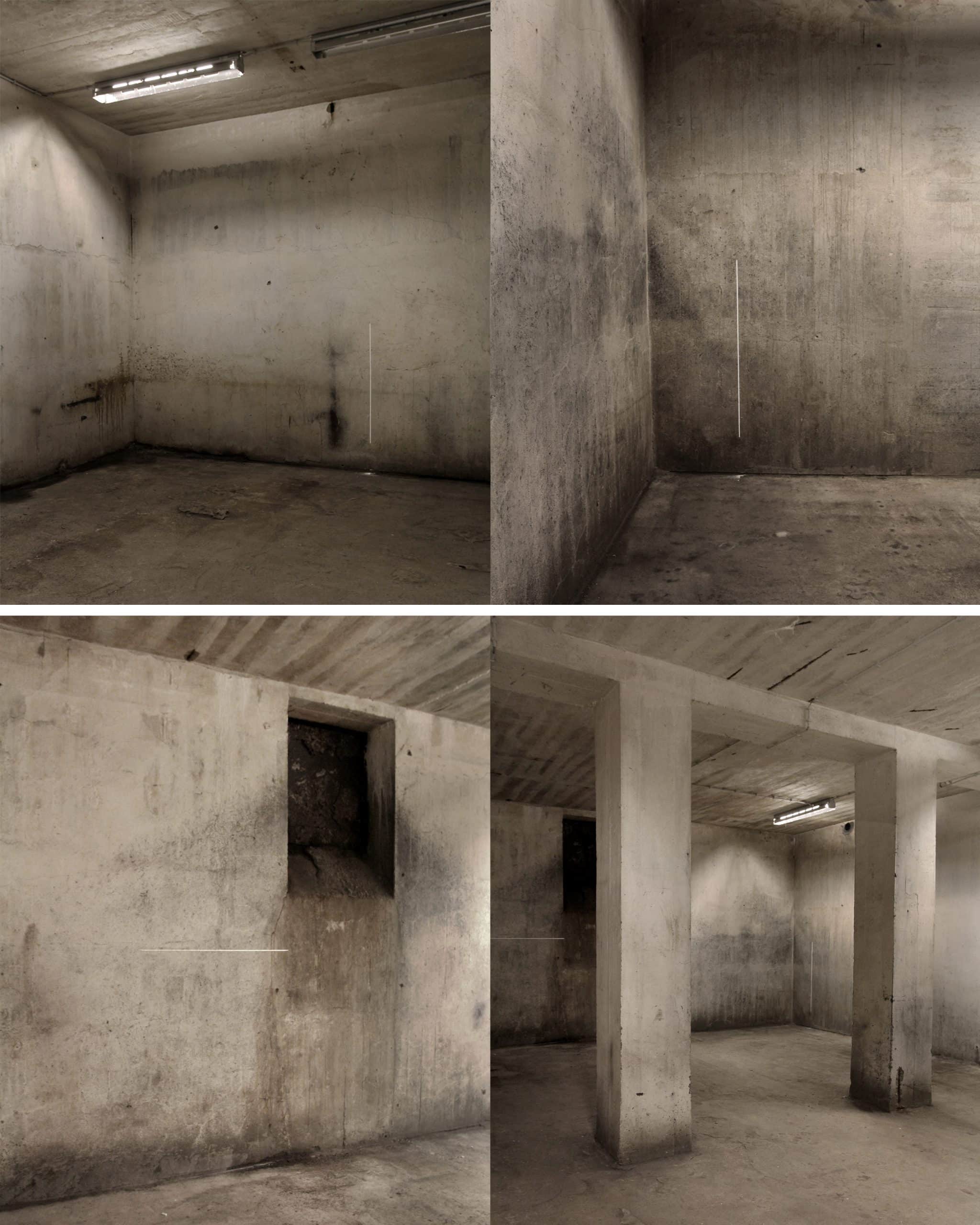

EH: I focus mainly on site-specific works that explore the relationship between form, painting and drawing in dialogue with the space in which they are made and installed. My experimentation involves the deconstruction of existing systems and a minimalist visual expression. My work is often characterised by rigorous geometries, challenging conventional categorisations and placing itself in a liminal state that encourages a rethinking of space and form.

IS: I’m very attached to the term ‘deconstruction’. The concept of deconstruction was introduced by the philosopher Jacques Derrida, who described it as a turning away from Platonist ideas of ‘true’ forms and essences that are valued above appearances. What’s your understanding of this concept, which in a way defines your practice?

EH: I do not literally base my practice on his concept of deconstruction, but I am certainly aware of it and I like his way of looking at existing patterns as multi-interpretable and dynamic. For me it describes a way of looking at things and working with elements to create art. It is, of course, a combination of constructing and destroying, an interesting friction between these aspects too. I like to deconstruct things in order to understand them better. Or to work with elements that seem forgotten, out of function, and give them a new light. Like patterns from forgotten futures. Elements, buildings and man-made objects that were part of a fully functioning system and have fallen out of it, I try to give them a new place or, like a classical artist, capture them on canvas, whatever the form or shape of that canvas may be. When I came up with this alias—Deconstructie—I was actually merely looking for an Instagram name to get into the virtual world and circulate my work. If you wish, the term ‘deconstructie’ (Dutch word for ‘deconstruction’) is in my vision also connected to De Stijl movement, Mondrian and Van Doesburg’s heritage. This is my take and my interpretation of their work: I see my own work as a deconstructed version of what De Stijl was all about. I truly love what they meant for the Dutch art tradition and I try to develop what they were doing, now hundreds of years later and adapt it to the time we live in now. However, there’s a certain degree of spontaneity in my choice for such a name.

IS: How do you choose your site of intervention?

EH: It is often a matter of being a passer-by, coming across buildings or areas that seem abandoned, left to nature. Of course it becomes a focus and sometimes you can feel where to go, where to look. For the past ten years I have been visiting these places quite often in the north of the Netherlands. My brother-in-law has a great feel for these places, and there are a lot of former factories there that have been left to fade away over time. On family weekends we make an early morning trip, sometimes arriving before sunrise.

IS: Why choose form, the basis of all art languages, why the naïve, primitive essence of wall art to trace human presence in an abandoned, let me say, post-human space?

EH: Basic traces like a line on a surface, just a simple shape or form, feel like respectful interventions to apply and leave behind. From the start they seem to be in dialogue with the space around them. Almost like ghosts from the past, symbols of industrial heritage. I often react subconsciously to the space and its obvious elements from the details in the architecture, to the shadows on the walls, or the corners that connect walls and spaces. In these spaces, time has fixed itself, nature has regained control, man has gone, but the energy is still there. I like to respond to this in a subtle but powerful way. I think it needs no more than minimal gestures that are resolved in a single session. I prefer not to work for months on a single painting, for example. My work doesn’t always have to be finished in order to be dynamic, and always changing.

IS: How do you feel your art being related or unrelated to graffiti art?

EH: That’s how it all started, with me reacting to a space like a graffiti artist. Years ago I did more complex paintings to then realise that minimalist interventions work well with the environment. I’m at a point where I’m also rethinking my black shapes and grid-based drawings. Will my signature style always be interesting? That’s what I ask myself. Placement and surface. Sometimes I have discussions with graffiti artists I meet whilst working. I myself used to do tags and street art when I was still a student. I also painted trains but was never really attracted to being one of many within the graffiti culture. The relation I have to space and time also changes but the feeling of adventure, the cutting of fences, climbing, and trespassing obstacles remain the same.

IS: What do you feel in the spaces you paint in?

EH: I mentioned that the energy of an industrial past is still palpable. These places were once vibrant and part of a dynamic process and hard work. There is an energy of beautiful decay and sadness at the same time. The elements of a system are slowly fading away, parts of it literally falling to the ground, soon to be demolished. There is a certain eeriness, but at the same time a hope for a better future.

IS: What’s the map of your interventions like?

EH: Well, you can definitely notice that most of my wall paintings are around the area where I live, or generally speaking, around the Netherlands. What remains unchanged is that I only paint in rough spaces. Polished environments are never my choice. Moreover, I travel occasionally and move around to make new works, especially when I travel for other reasons and find myself exploring the industrial sites around.

IS: Do you keep track of your art pieces and do you go back to record the decay they go through?

EH: Photo souvenirs are my way of documenting such works but I don’t feel bad when my art is demolished by time and atmospheric agents. There’s sadness in places that disappear to give way to gentrification, that’s for sure, but there’s also something poetic about time passing. Whilst I do find the photographic documentation of my artworks essential, I don’t specifically plan to take photos of them to document decay, although it’s interesting to see my paintings after a couple of years to see how they’ve interacted with external conditions.

IS: Your work is heavily vehiculated by images of yourself that you carefully produce yourself, as if trying to build an archive of deconstruction, site by site, form by form. How did you arrive at this method of circulating your own work in the digital realm? Something that adds another layer of contextualisation to your artistic act on site.

EH: I like to think of my interactions as a human being with the space around me as fluid and multi-interpretable. I also like to see reality as divided and interacting within multiple dimensions. For this reason I like the classic act of painting form on a surface, but also form in space, although this space can be visual or non-physical space. All elements become part of a dynamic environment that is constantly deconstructing. Always between construction and destruction. I think documenting, placing, replacing and working with ready-mades are also part of this way of interacting with the world around me. In this way, an intervention on a wall is not simply finished after painting. I can document it and continue to work on that documentation digitally or work with printed versions of it. I also like to take samples and continue in this way. So, all in all, line, shape, mass, form and my personal actions in relation to the space in which it is created are constantly reinterpreted and are constantly changing elements in my work. I like the fact that a lot of my work can be seen as minimal art, although I am trying to break with the rather static nature of that.