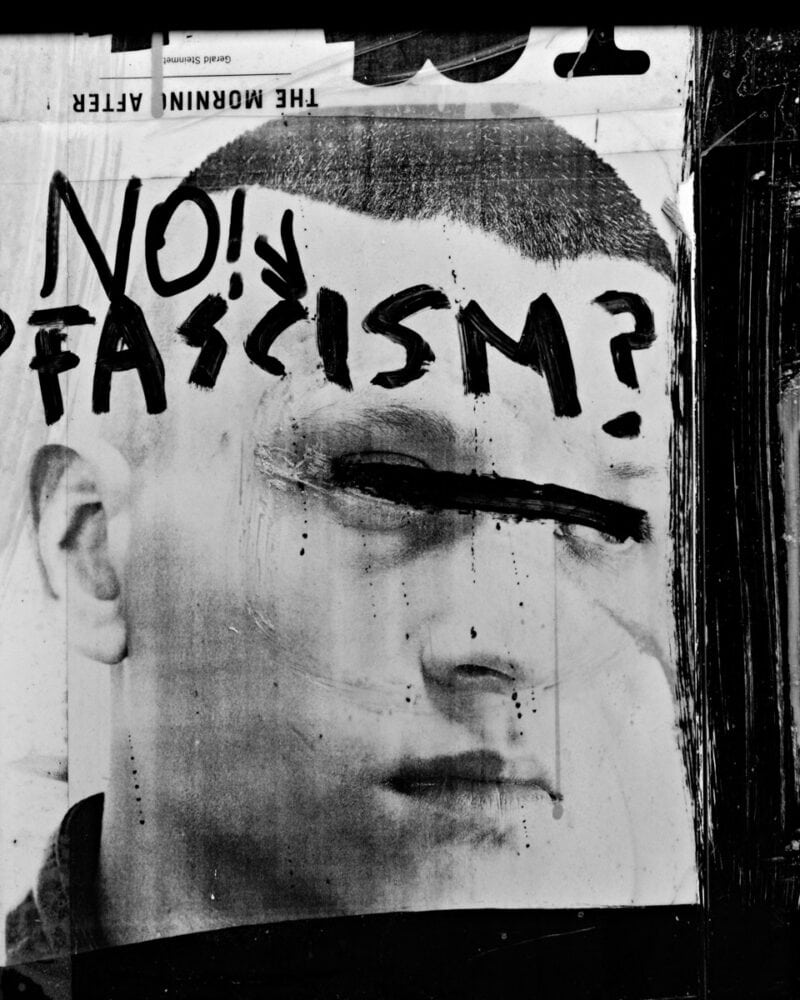

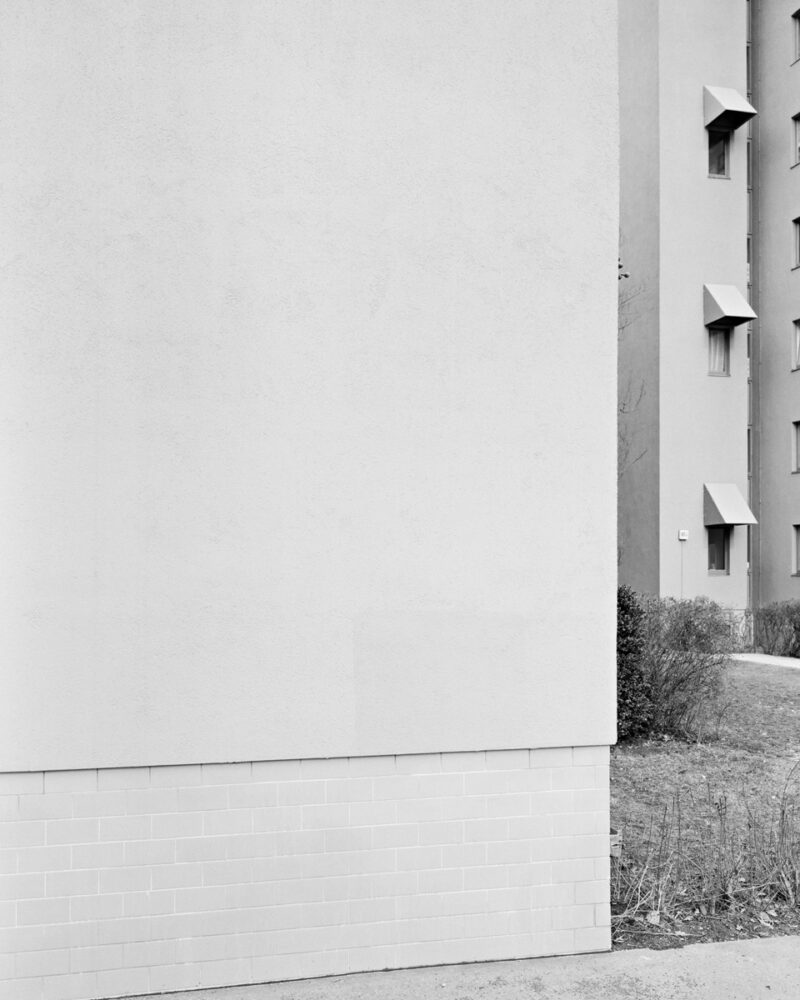

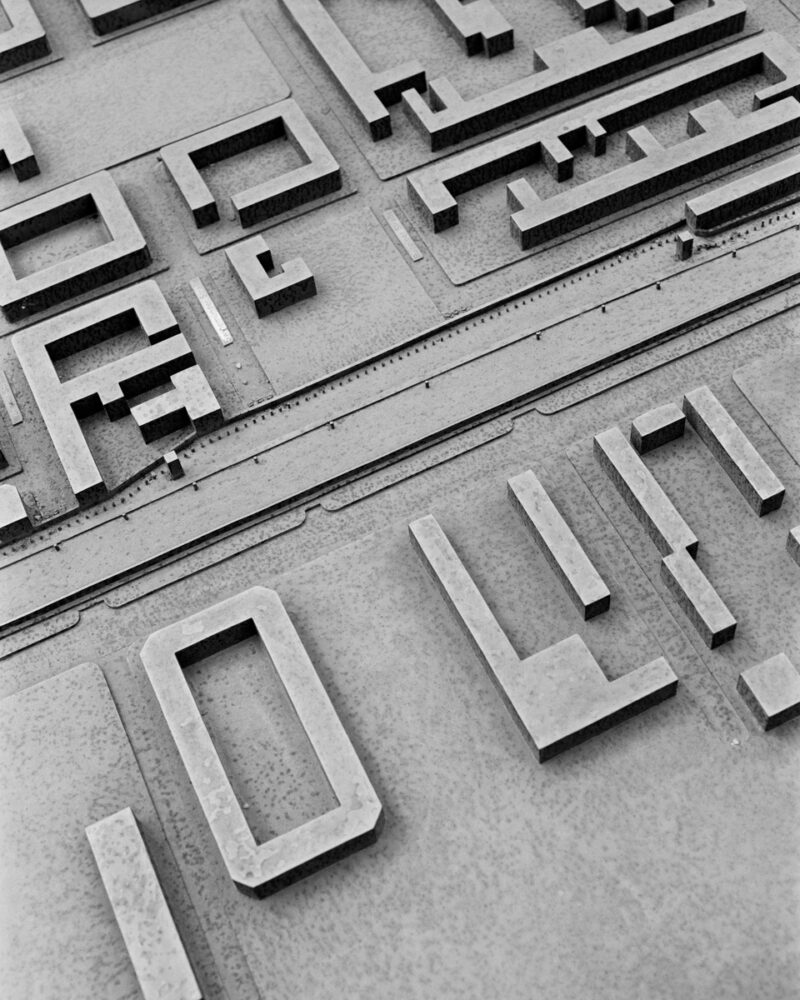

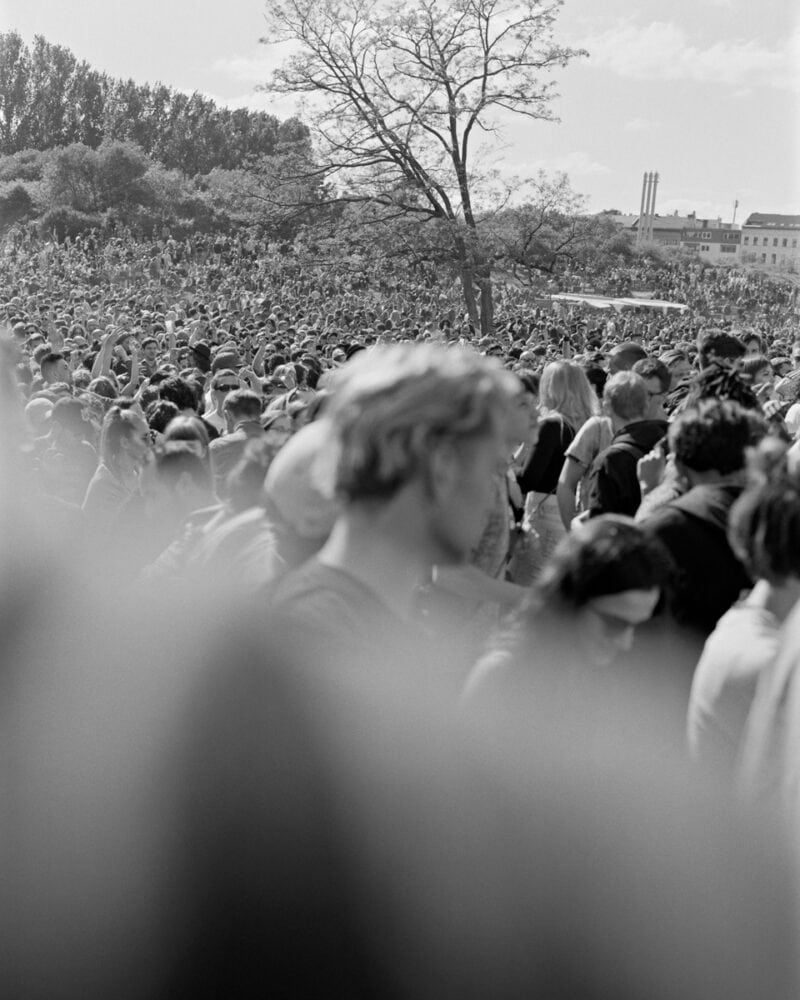

Bertrand Cavalier explores the interactions between people and their environment. Exploiting photography’s ability to penetrate the tissue that binds individuals together and embeds them into their surroundings, he creates poetic renditions of singular moments, rather than objective documents of social phenomena. Cavalier’s images reveal how the socio-political order informs everyday life through architecture and the urban landscape. At the same time, however, his interest goes out to the process through which people restructure the space they navigate and make it their own. As such, his photography attests to those aspects of everyday life that creatively appropriate dominant ideology and in doing so, resist it.

Cavalier’s series ‘Concrete Doesn’t Burn’ has been published in 2020 by Fw:Books. In 2019, he received the Sébastien Van der Straten grant for his ongoing project The Grid System. His work has been published with Futures (European platform for photography), PH Museum, GUP magazine and was presented during Plat(t)form at the Winterthur Photography Museum. Cavalier exhibited at FOMU Antwerp, FRAC Orléans and BredaPhoto, among others.

About ‘Concrete Doesn’t Burn’ – words by Taco Hidde Bakker:

The twentieth century saw many old European cities riddled with bullets and reduced to rubble by bombs. In the case of Belfast and Sarajevo, the wounds caused by armed conflict and war are still fairly fresh. Traumatic ruptures to the urban fabric of cities levelled during the Second World War can be felt to this day, for example between pre-war architectural styles within towns that had grown slowly and organically over time on the one hand, and post-war, modernist urban planning and hastily rebuilt city centers on the other.

Bertrand Cavalier, who sensed a strong social separation between the cheap housing districts and the older parts of his hometown of Montpellier (France), wondered to what extent the built environment exercises influence on the lives of its inhabitants and their views of the future. Starting in Cologne, he photographed cities including Berlin, London, Le Havre, Rotterdam, Budapest, Warsaw, Belfast, Mostar and Sarajevo. But while Cavalier initially focused on rough, functional buildings and districts, he went on to portray the people who live there and who testify to a city with a different—and perhaps more intense—soul than it would appear from mere assemblies of building materials. Cavalier shows that they have a character at once vulnerable and reflective of the obstinacy of the seemingly indestructible buildings in and among which they live.

The fact that concrete does not burn may create an impression of safety, but it could also mean this post-war heritage is here to stay for a long time to come.