8:10, Milano Centrale. Boarding the train to Lausanne, I find myself reflecting on the randomness of things. Maybe it’s not a coincidence that I’m traveling to visit Soleil·s, the second edition of the Solar Biennale. Maybe it’s not a coincidence that after days of cold and gray weather, the sun is finally shining in Milan. But we never really talk about this. Have you ever noticed that when we find ourselves in a place with other people, the first thing we often do to break the ice is talk about the weather? I say “often” and not “always” because this usually happens when the weather is bad. It’s easier to complain about a lack of sunshine than to be grateful when it finally appears.

During these two days at the Solar Biennale, I realized that when the sun shines, we need to notice it. Because it is one of the most precious and accessible sources of energy that our planet can benefit from. Hosted this year in Lausanne, across mudac (The Museum of Contemporary Design and Applied Arts) and the EPFL (The École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, a public research university) campus, Soleil·s opens from equinox to equinox (03.21/09.21.2025)—the period of the year when we experience the most daylight. Is there a better way to welcome the sun?

Our experience begins at mudac, now located within Plateforme 10 and designed by Aires Mateus. We start our visit with an anecdote: Plateforme 10 is adjacent to Lausanne station, which has nine tracks. This cultural hub symbolically represents the tenth track—a new departure, this time into the world of art and design.

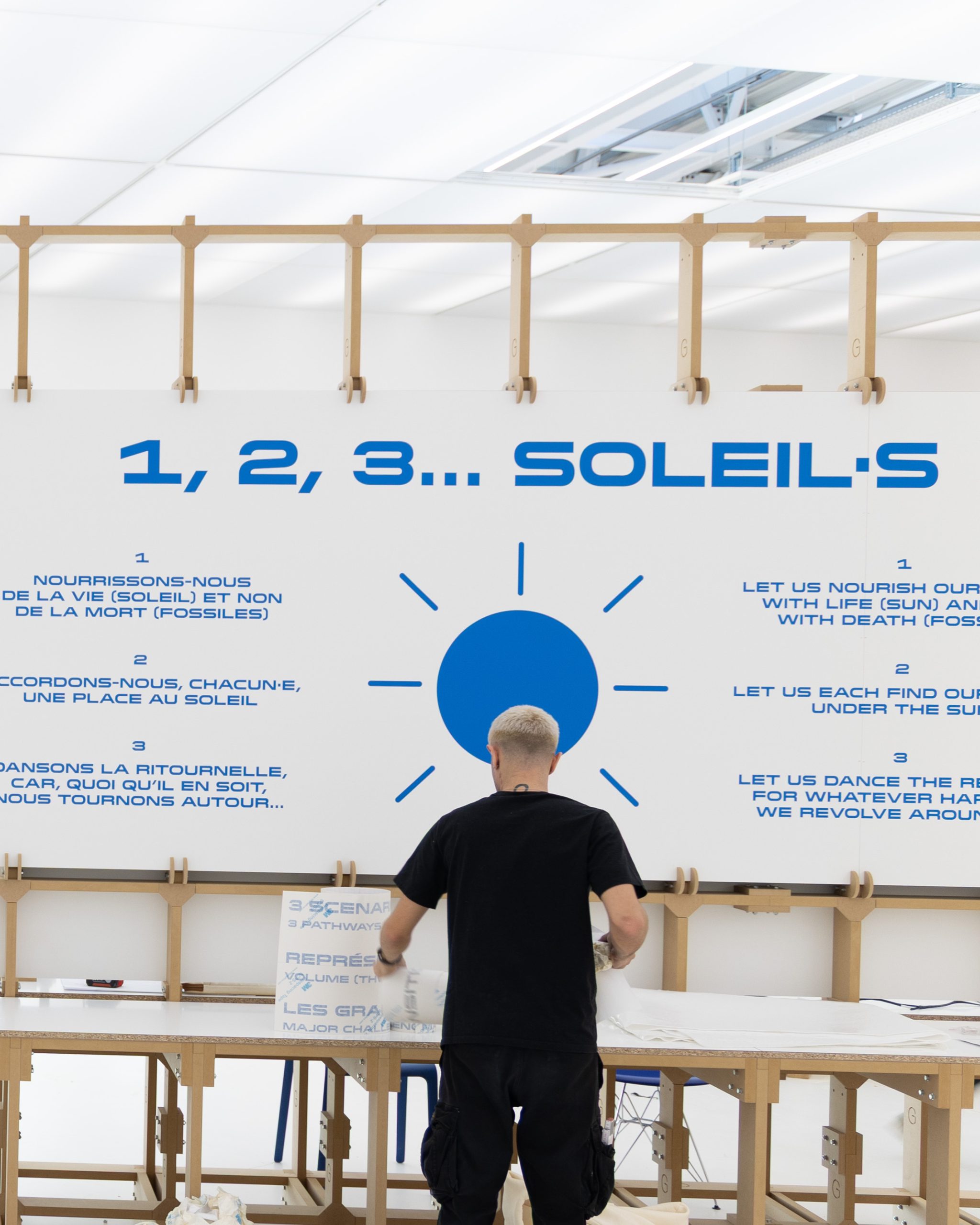

The Biennale is the first chapter of the Solar Movement, founded by solar designers Marjan van Aubel and Pauline van Dongen. Together, they imagine new relationships between design, science, technology, and solar energy. Soleil·s doesn’t dictate—it invites. Through installations, films, archives, and games, it encourages visitors to think, feel, and experience the solar transition as something cultural, emotional, and deeply human. But more than just an exhibition, it’s a journey. Embracing eras, mindsets, and transformations.

Among the many insights, some works particularly captivate me. Here is a small guide to navigating my personal illuminations.

Monte Verità

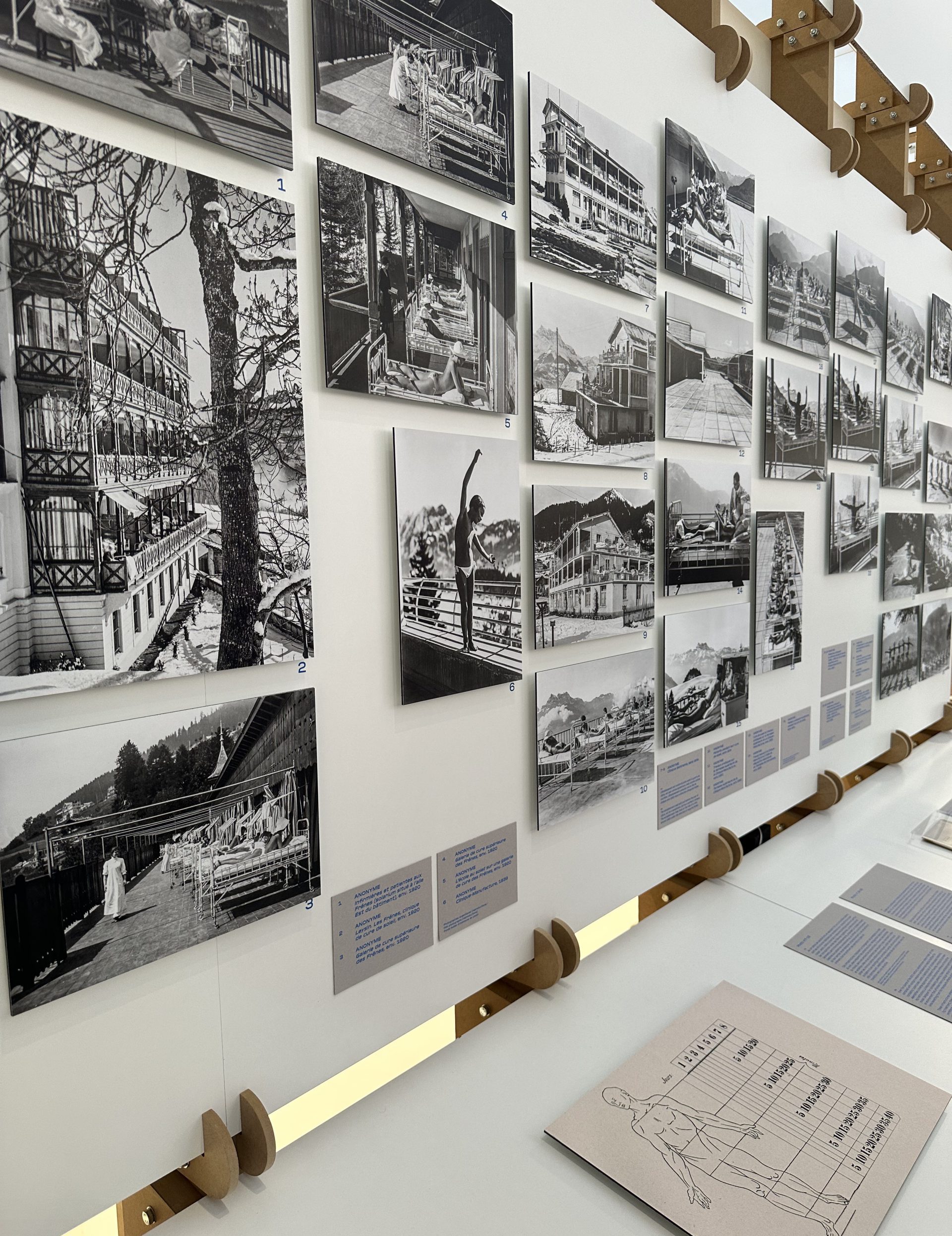

This photographic series catapults us into the past before bringing us back to the present and future. Monte Verità was a utopian community born in Switzerland in the early 1900s—a refuge for artists, thinkers, and reformers seeking an alternative to industrial society. A place to re-establish a connection between body, mind, and the world, founded on simplicity, light, and communion with the living. The installation invites us to reflect on how those pioneering visions can inspire our contemporary approach to solar energy and paradigm shifts.

Under the Sun of Sanatorium

A visual journey that explores the therapeutic use of sunlight, particularly in sanatoriums, where sun exposure was an integral part of treatment. Documenting these places set in the early 20th century in Swiss alpine locations, the installation reconstructs how light was used in architecture and medicine to improve well-being, particularly in the fight against tuberculosis. It serves as both a historical journey and a reminder to rediscover the connection between natural elements and human health.

Have a Nice Day (2024-2025) by Common Accounts

A source of life but also of risk: an installation that stages the paradox of the sun. Featuring an artificial sun, it invites visitors to lie on sun beds and enjoy its warmth, sounds, and light frequencies, emitted through different technological devices. A narrative that oscillates between the joy of light and awareness of its harmful effects, such as excessive exposure. This work compels us to question how we can balance our relationship with the sun without falling into extremes.

Sea, Sex, and Sun

The sun as fantasy, commodity, product. This visual timeline dissects advertising, tourism, and media, showing how the evolution of summer bodies reflects societal changes. The sun is a supplier of aesthetics, inviting commerce and social aspiration. The aesthetic ideal of the female body presented by fashion magazines each summer, sculpted by sunlight, transforms the skin into a screen on which all the aspirations of an era are projected. Bodies become a visual discourse of desire and consumption, imposing often unattainable aesthetic standards.

The Right to Day (2025) by Vraiment Vraiment + Marilyne Andersen

This work explores the necessity of natural light exposure for humans, considering each individual’s physiological and psychological specificities. It invites you to follow a three-step journey: determine your personal chronotype; learn how to adapt your domestic light habits to minimize negative effects on your biological clock; identify your sensitivity and create your personalized Daylight Rights card. The installation made me aware of how essential sunlight is to our well-being. Through a customizable use of light, we can improve our personal health and life.

The Idea of a Tree (2008-2025) by Mischer’Traxler Studio

A project exploring the relationship between nature, technology, and autonomous production. It demonstrates how design can interact with nature sustainably. Using solar energy, the machine produces objects (such as benches and lamps) in real time, with rhythm and aesthetics determined by the intensity of sunlight, just like the growth of a tree. It is a metaphor for time and the environment, translating natural variables into physical objects. Combining craftsmanship, technology, and sustainability.

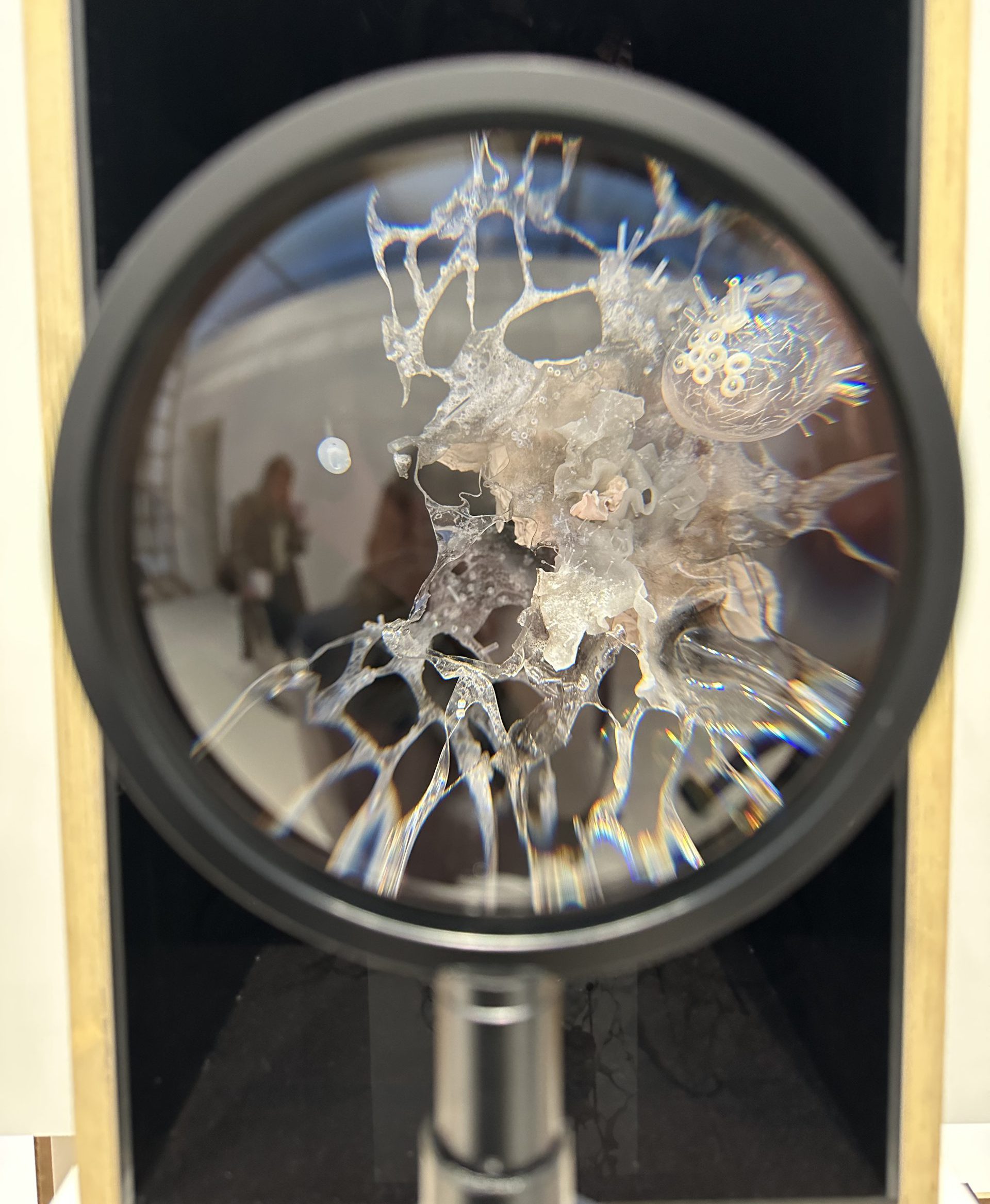

Fellaria’s Time Capsule (2024) by ТАКК

An installation addressing climate change, collective memory, and humanity’s relationship with the environment. A sort of time capsule that captures and preserves traces of the Fellaria glacier in the Italian Alps, highlighting its fragility in the face of the climate crisis. It invites reflection on our role in conservation and on the memory of endangered ecosystems, turning the glacier into a living testimony of time passing.

The second part of our journey takes us to EPFL, where the Biennale continues its exploration. Entering the campus feels like stepping into a parallel future, filled with striking architecture and visionary ideas.

Here, we visit Sun Shines on Architecture at Archizoom, an exhibition that explores the intersection of sunlight and architecture. For centuries, architecture has had a fluctuating relationship with the sun—an ongoing dialogue of attraction, hesitation, and promise. We discovered how, over time, the evolution in designing buildings in relation to natural light—not only for energy needs but also for comfort and aesthetic purposes. It highlights how we can turn the sun from a passive presence into an active architectural element. Because their futures are inseparable.

At EPFL, we also have the chance to enter the hyper-scientific. The exhibition From Solar to Nocturnal premieres Staring at the Sun by Alice Bucknell and Interspecies Interfaces (Part I) by Matthew C. Wilson and Emilia Tapprest, two compelling audiovisual works that expand the Solar Biennale with innovative storytelling and immersive formats. Bucknell’s installation speculatively explores the intersection of solar energy, AI, and climate futures, while Wilson and Tapprest investigate interspecies communication through experimental interfaces. These productions enrich the Biennale’s discourse, weaving a narrative from the solar to the nocturnal. Using cutting-edge digital techniques to challenge perceptions and imagine new relationships between technology, ecology, and non-human entities.

If day one was about concepts, day two is about contact. Thanks to a series of scientific tours at EPFL, we move to the beating heart of solar innovation. This is more than just a continuation of the Biennale—it is a descent into the core of the sun itself, each lab bringing us closer to its essence.

Led by director Marilyne Andersen, LIPID (Laboratory of Integrated Performance in Design) explores the human experience of light through both architectural and physiological lenses. We learn how discomfort—glare, shadows, imbalance—can be just as significant as the absence of light. Through immersive experiments, we see how the eye’s response to sunlight shapes architecture. One standout project measures how much glare we perceive depending on the filters and colors applied to building façades. Their mission is to optimize buildings for both comfort and daylight—to ensure enough natural light without overexposure. This lab reminds me that comfort is not passive—it’s something that can be measured, modeled, and improved. Because “it is through the light in our eyes that we define our vision.”

From light perception to light transformation. At LRESE (Laboratory of Renewable Energy Science and Engineering), we explore how concentrated solar energy can power chemical processes. Imagine this: solar light is captured and focused into a reactor, where it can transform water and other inputs into usable chemical products. It’s a reactive force, a tool for transformation. Watching these processes in real time triggers something in my head: the sun is not just overhead. It’s working, actively, silently.

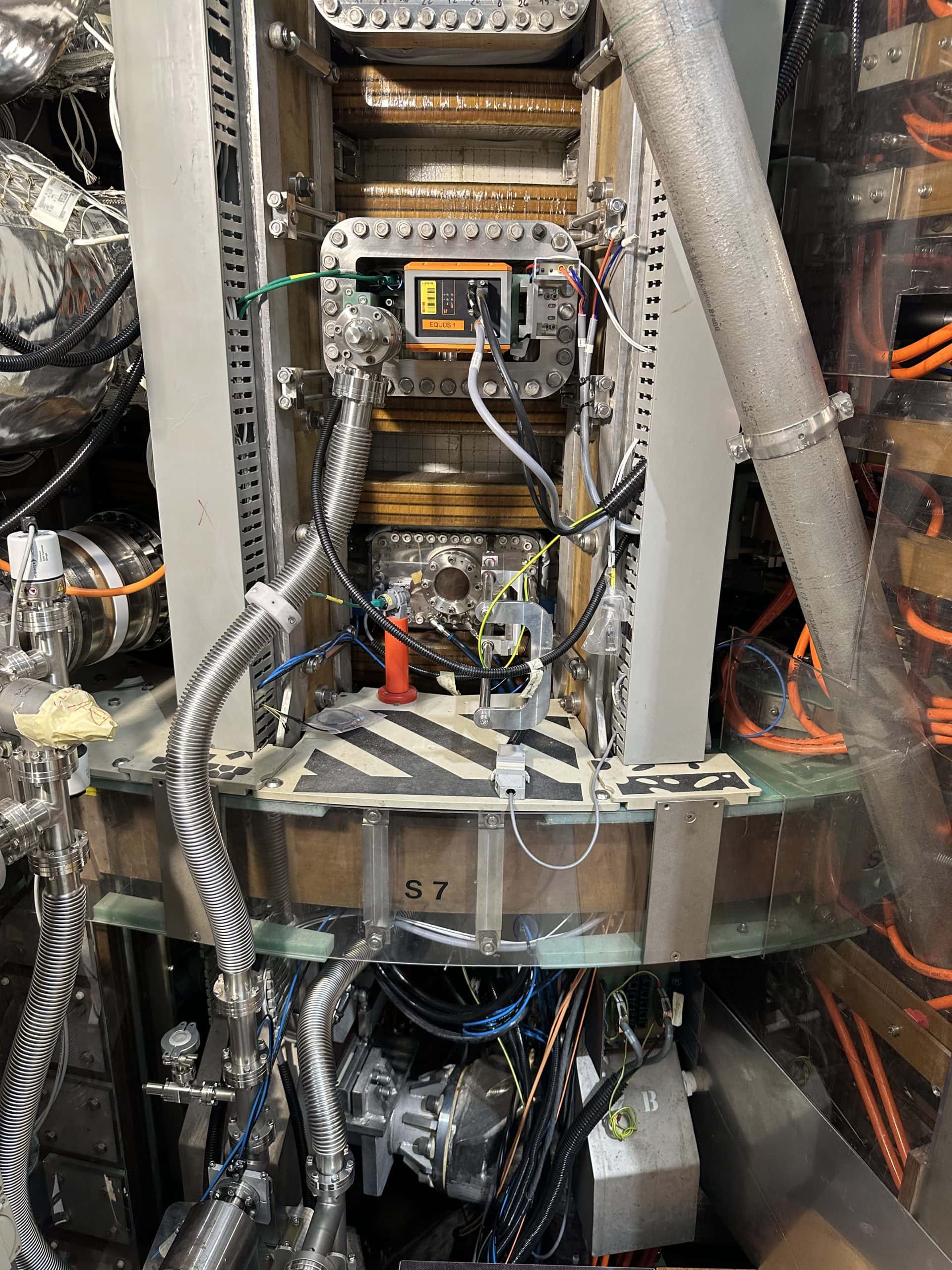

Our last stop takes us deep into the realm of scientific discovery. At the Swiss Plasma Center, scientists and researchers are attempting to recreate the conditions of the sun on Earth. Through fusion, they seek a clean, safe, and scalable energy source that converts matter directly into energy, simulating the incredible forces at work in the heart of the sun. Every 15 minutes, for two seconds, they conduct an experiment. Always different, always unique. And those two seconds are enough to observe, measure, and collect everything they need. Welcome to the center of the sun, replicated right before our eyes.

And then, it’s time to leave. Still immersed in this unique and enlightening experience, after two days bathed in sunlight, I wonder if I will still find the sun on my return to Milan. But perhaps the answer is to never stop looking for it.

Soleil·s showed me that transitions are not only necessary—they’re sexy. They shimmer. They pulse. They demand attention. I leave with new questions, new tools, and a deeper connection to something as simple—and as complex—as sunlight.