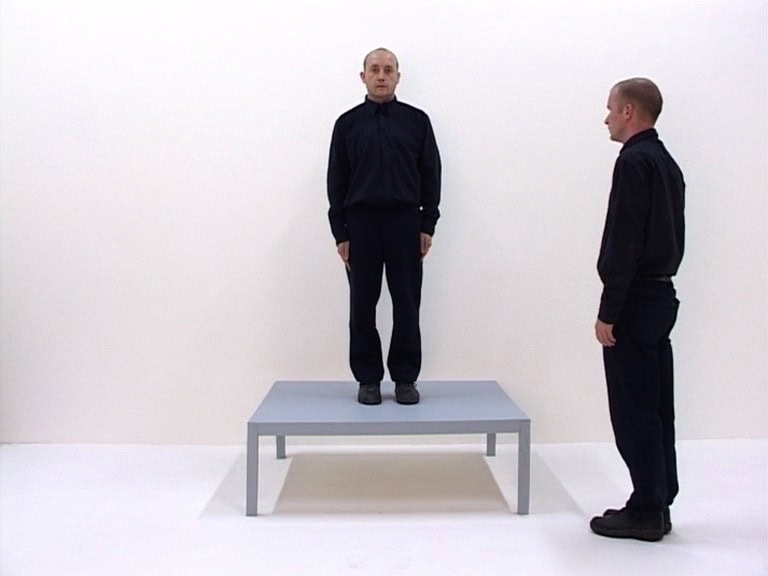

Artistic duo John Wood and Paul Harrison have been exploring conceptual and ironic situations through video art and, most recently, text-based works since 1993. They create actions in which the human body and everyday objects are used as instruments to explore space and to experiment with the laws of action and reaction. Playing around with the most object of objects and their own bodies, the Bristol-based duo record the possibilities of actions within a set of rules and a fixed space and time, animating inanimate everyday objects and places. It’s the very loss of control that allows them to find the extraordinary in the ordinary, both ambiguously perceived as ironic and dark. Here we discuss their 32-year-long practice, the ordinary, being clueless, and opening up to situations where time and space (the limits of the video screen, a white room, or the blank page where their actions are conceived) frame action and inaction, emptiness of meaning, and deep truths about life as it is.

Ilaria Sponda: Who are Wood and Harrison? How did you come together?

Paul Harrison & John Wood: We are John and Paul, Wood Harrison, Harrison and Wood, John Wood and Paul Harrison, John Harrison and Paul Wood, JWPH, Paul and John. We use every different possible combination of our names. It’s a small thing, but it shows how we view our whole practice. We never correct people unless they get our names genuinely wrong. We’ve never been worried about who came first and that really does reflect our practice. We are careful, serious and considered in our work on the one hand, but we’re also quite relaxed about things that we don’t think are that important. Does that make sense? Essentially, we’re just two people who spend a lot of time trying to do things in a room. We met at art school in the late 1980s, which is a long time ago and feels like a long time ago in both good ways and bad. We’re friends, that’s the vibe. We’re not one of these duos that need to fight to get that creative spark. We’re open to discussion and we have our own opinions of course, but we’ve never really argued about things. In a nutshell, we’re two friends that like doing things together.

IS: What’s changed in 30 years of working together? What hasn’t?

PH & JW: Well, we don’t have any hair now. That’s one thing. There are lots of things that have changed and developed. What certainly hasn’t changed is the fun we have making things. Despite the frustrations that can arise within the art system, we’ve managed to maintain the silly fun of being in the studio together. No time has passed whatsoever in that sense.

IS: Being clueless seems to be the crux of your artistic process. Things and places as they are inspire your creativity. It’s quite a practice of resistance at a time when a surplus of information has caused such fleeting attention spans.

PH & JW: We do still manage to amuse ourselves with very little but technology definitely makes things a lot easier. We’re not tech heads, we’re not experts in technology, but we do love anything that makes life easier for us. There are many ways to ‘be an artist’ or more precisely to ‘become an artist’ but things are so different nowadays that we wouldn’t be able to ’become artists’ in the same way. We took our time but things are faster now and more demanding maybe. When you’ve been around for a while like us, you notice things changing. Trends or fashions fade and then come back and then fade again and come back again. It’s not about being ultra-intelligent or anything. It’s just about being around and noticing things. And I think the first time it happens, when there’s a dip or you feel out of place somehow, it’s a bit scary but then you kind of realise that that is going to happen and you look at older artists from generations before yours and you realise that it probably happened to them too. And then maybe one day you’ll be completely forgotten forever!

IS: – Your speculative practice opens space for discussing and considering alternative possibilities and options as well as imagining and redefining our relation to reality itself. What role does humour play?

PH & JW: We’ve become the work now. There’s less distance between us in real life and us involved in the work. We were quite young when we first started working on our ideas and we were trying to make things without being entirely sure what we were doing. We spent a lot of time figuring out how things worked. When we started distributing our video works people reacted with laughter or with mild amusement. That was a bit of a surprise but incredible, especially when we were first starting out and doing a lot of film festivals. We would be sitting there in the audience and people would laugh. We have noticed how the response to our works is different in each country and context it travels to.

IS: Have you ever thought about how people perceive your works differently in relation to their culture?

PH & JW: There was a piece of work we made a few years ago called A Hundred Falls where Paul falls from a ladder multiple times. It has all sorts of references to 1970s television and special effects and all that kind of stuff. When we showed it at Studio Trisorio in Naples, people were watching it for a really long time and discussing how it was about the financial crisis. We thought that was amazing! One of the things we want is for our work to be very open. We have our own ideas of what we think it is about and what it means but we aim to leave room for people to interpret it in their own way.

IS: Do you think of your work as culturally accessible to everyone?

PH & JW: We hope so. Our earlier works were perhaps more accessible generally as we didn’t use language and so we found, initially, that the work travelled really well, especially for film festivals as mentioned before. There are linguistics barriers now that we’re using language a little bit more and the work has changed and shifted. You have to be careful about universality because not all people have the Internet and TV so something can never be fully accessible in that way.

IS: What does that initial blank space mean to you?

PH & JW: Initially, it was a choice dictated by the economics of making art. When we first started, white paint was cheaper than any other colour. And we’ve always done drawings or diagrams of what we’re going to do on blank sheets. We naively thought of ourselves as being these figures made real on the screen. Undoubtedly people were saying our use of white spaces was a critique of the white cube gallery space but honestly we were motivated purely by finances and graphic composition. When we first started, the cameras we were using didn’t handle colour particularly well and you would get a lot of bleed which was very annoying!

IS: If you had to set up a creative exercise with the “chairest of chairs”, to use one of your own terms, what would it be?

PH & JW: The thing about the “chairest of chairs” comes from the constant search for an extra level to add into the videos to entertain ourselves. We go on a quest to find the thing that looks most like the picture in our heads, only to realise that we make all sorts of assumptions about objects that are familiar in theory. If we had to set up a creative exercise, it would be to hang a jacket on the back of a chair in as many different positions as possible—a simple thing that people do every day without really thinking about it—and everybody could make a little film about it. Just really tiny unspectacular things.

IS: In the era of algorithms, we are increasingly less likely to face contingency. All the content we come across is tailored to our past activity while in real life we tend to be so dispossessed from our bodies that we don’t pay attention to the ordinary, generally speaking. In this regard, how do you want your work to communicate with people?

PH & JW: It’s so interesting because it’s a generational thing, although we have played video games online and stuff. We always think that, in the end, the medium that connects us to the virtual world is a physical object that you can drop and smash or leave somewhere or lose. So, even though this is your access point to infinite possibilities for connection and communication and so on, it’s still a lump of plastic and metal with a battery that can die. Technology is used by humans and we are fallible. And we forget that and disconnect from the idea of what that stuff is. We’re constantly reminded that we’re imperfect and that we miscommunicate. That’s where the humour comes from within that embarrassment of falling over or forgetting something. To us, technology and our interaction with it is kind of fun but I guess that’s partly because we didn’t grow up so immersed in it. We’re probably quite slow in digesting things that come in as new technologies. We’re using technology but in a very basic way. All this business is a completely different language and it’s extremely fascinating because it changes how people relate to each other in the real world. It does have massive implications for how we operate in society and how we interact physically. I think it pays to be tuned in so that you know what’s going on. I’m not saying that we’re down with the kids but technology is fun and it’s another potential tool.

IS: What are your favourite ordinary objects?

PH & JW: Pens. Not an expensive pen, not the cheapest pen, but a reasonable pen. We’re not collectors. It’s more like a kid’s book of objects: b is for bag; p is for pen. That’s part of the thing about us becoming the work. It’s that simplicity in relating to the world and the things that we carry and just the satisfaction of a really simple thing that works. And then the other side of that is that you’ve got a pencil and then you’ve got an airplane and they are both ordinary objects.

IS: You make art to understand the world through definitions. What is it about definitions that nurtures your creative process?

PH & JW: That’s what we use language for because we’re not academics. We use it as a material that’s kind of elastic and plastic and that doesn’t have to have those rules. It’s fascinating how the decision to add one word or remove another changes the whole meaning. Language has always been present in our works. It’s been a really slow process of working things out. If we’re going to make a painting, what kind of painting would we make? How do we use language and what do we do with it? There should be coherence as our practice grows and we do different things. That’s not for us to say, but hopefully there is.