What sound does an orchestra of lights make in an empty hall? According to Berkely, probably the same as a tree falling in an empty forest: no one. But unlike the falling tree, at the Olympia Music Hall someone behind the scenes is directing the show, giving meaning to that silent spectacle. It is Alice Guareschi, who stages a poem with light, marking the time with a tight sequence of shots. Je m’appelle Olympia is the story of a theatre that comes to life. Of the space in which stories inhabit, which decides to tell its own. And of a narrative suspension in front of which the spectator no longer knows where he is—nor does he fully understand what he is witnessing. But in the end, he somehow comes out different.

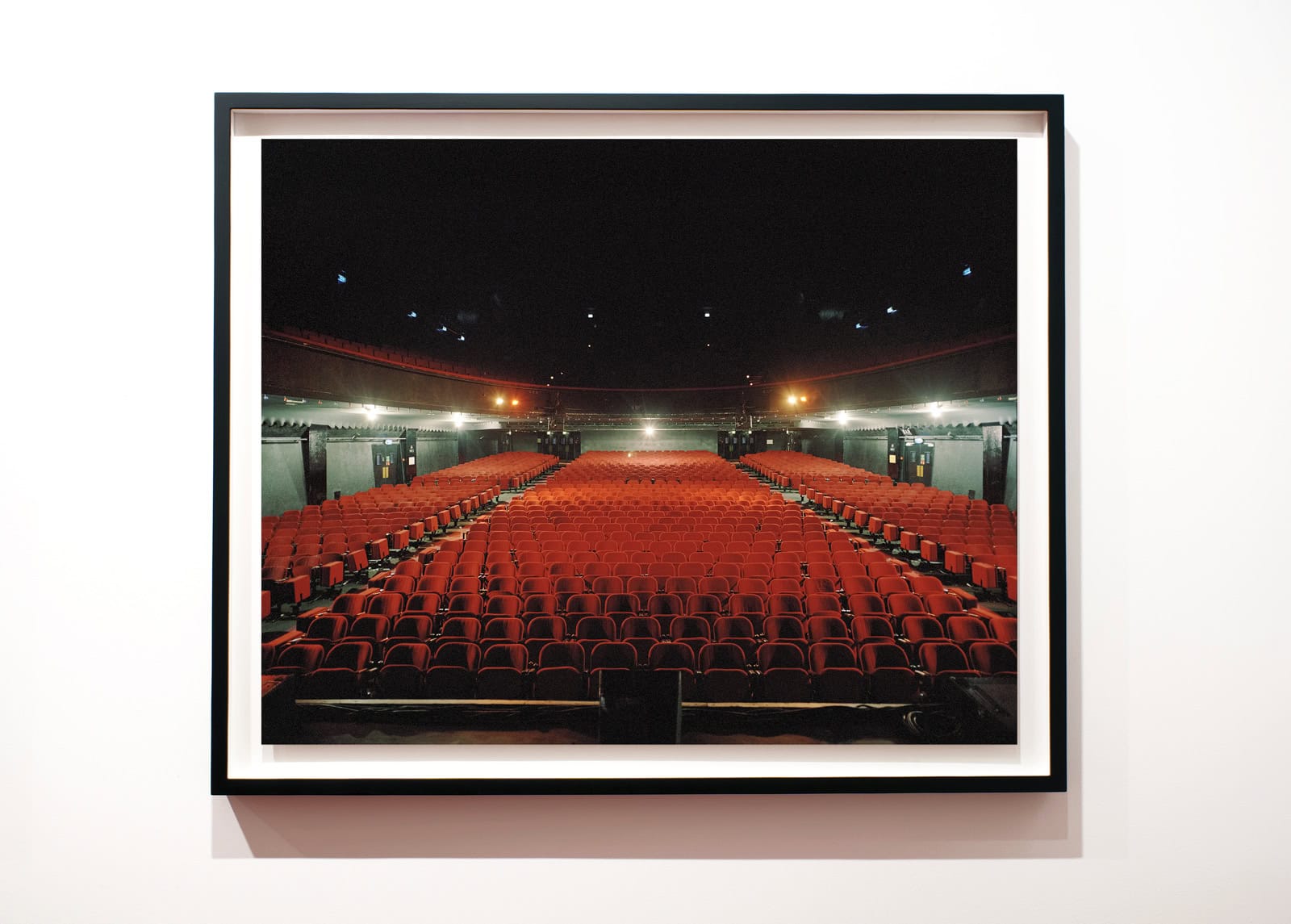

Je m’appelle Olympia is an action for house lights performed by Alice Guareschi on just one occasion at the Olympia Music Hall, the legendary and iconic Parisian venue, on April 12, 2012. The sixteen photographs that make up the series on show at MAN were shot on the same day, right after the live activation of the light choreography in the theatre’s empty space, which involved all thirteen of the coloured lighting channels that are permanently integrated into the architecture. With a fixed framing, similar but not identical, following the precise original lighting score composed by the artist, the images present a sequence of different movements of lights in the auditorium. The photographic series thus becomes a new synthesis of the image-idea and intention behind the performance: to activate a theatre when no show is happening on stage, to play it live, to reawaken its latent memory and the secret life that eludes the spectator’s gaze. By breaking down the duration of the action into photograms that can be viewed either separately or all together, the spatial arrangement of the work now makes it possible to embrace the overall idea at a glance.

Robin Sara Stauder: What happened during your first night at the Olympia Music Hall? How did the light show manage to bracket the sound play?

Alice Guareschi: Although I have lived in Paris for a long time, at different moments in my life, I was only at the Olympia for the first time in November 2011, for an Anna Calvi concert. I often go to the cinema or theatre alone, I really enjoy doing so, it allows me to watch and listen with greater intensity. I was also alone that evening and, at one point during the concert, I physically felt the emotion caused by the movement and fading of the lights in contrast to this magnificent theatre’s somewhat romantic monumentality, which bears the signs of time and all its stories. Beyond the music, over the stage. By the end of the concert, I could not leave the hall, and as it emptied from the audience, Olympia became more and more imposing, magical and mysterious. I left last, with the desire to make its architecture itself the main character of an artwork, to turn Olympia itself into a spectacle, no longer just the elegant frame or the iconic background of something that happens on stage. The opportunity came a few months later, when the Pavillon of the Palais de Tokyo decided to celebrate its tenth anniversary with an exhibition entitled This and There, curated by the artist Claude Closky, in the spaces of the Fondation Pernod Ricard. The idea behind the show was for each artist to choose a place or a time outside the space (There) where something would happen (This), the trace or coordinate of which would then be present in the exhibition. I chose Olympia. I proposed to activate the theatre with a light choreography, an action written for the house lights only, to be performed only once, for a chosen audience of guests. Une pièce unique. Without this production context, and without the generous helpfulness of Colette Barbier, the then-director of the Foundation, I doubt I would have ever had the entire empty theatre at my disposal. It was fantastic!

RSS: Je m’appelle Olympia immediately evokes a personification of space. How did you perceive the theatre coming to life?

AG: As I said, it was a physical sensation, an intuition even before than an idea. Sometimes places speak to us, or unexpectedly reveal themselves. The image that took shape in my mind was that of a choreography of lights that suddenly come on in the empty space of the auditorium, at a time of day when no show is scheduled and the theatre is resting, uninhabited and silent. Like an explosion of energy that has accumulated over the years; like the unexpected revelation of a secret life which concerns nobody except the building. What has Olympia experienced? How many things has it seen? How many stories have intertwined over the years under its electric blue vault? Privileged spectator, silent witness, intimate confidant, historical memory, space of the possible. The first-person singular gives it back a leading role. It is the theatre itself that speaks.

RSS: How has your perception of the venue changed from spectator to director? What does it mean to conduct an orchestra of lights? What rhythm defines the score?

AG: I first worked on the rhythmic composition, writing a score for the thirteen of the coloured lighting channels that are permanently integrated into the building, then I designed a choreography, where lights instead of bodies acted live in the space. The time of the live action was central. At that moment I thought: I am playing the theatre. A concert for lights solo. For someone like me who has never learnt to play an instrument, but loves music deeply and has seen dozens of concerts in front row right by the speakers, it was an incredible experience. Incidentally, the switchboard that controls the house lights was behind the stage, in a position that does not allow the person activating it to see the hall. So I had to ask a technician to press the buttons for me, according to the instructions I whispered to him in my headphones, while I stayed on stage, hidden behind the closed curtain. Like an orchestra conductor, listening to the space I dictated the rhythm of the picture changes, of the entrances, exits, pauses and fades. Those entering the theatre found themselves at first in a completely empty, silent space, immersed in a suspended semi-darkness. In front, the closed curtain, almost as if to deny to the gaze the habit of addressing the scene directly. As long as all of a sudden the lights began to vibrate, charged with electricity, fibrillating, until they exploded in a rhythmic movement that lasted some thirty minutes. Then, suddenly, with a fade to black, the return to penumbra. Only the light of two red quartz crystals vigilantly watching over the room.

RSS: The alternation of light and dark suggests a mystified message—a Morse code for the soul. What emotions does it want to evoke in the spectator? What does Olympia say after introducing itself?

AG: Olympia speaks a mysterious language that I am not interested in decoding. Likewise, with my work, I never intentionally try to evoke some predetermined emotion in the viewer. Or even less to say something definitive, with no room for interpretation. The artworks are there, they are in the world, and they must resonate with the viewer. What interests me greatly, however, is the image at the origin of the work: that of a theatre that suddenly come on in, in the absence of any show. A gorgeous bachelor machine.

RSS: What is the role of the image in the rendering of the performance? What part does omission play in the evocation of a concept?

AG: The images that make up the series were shooted the very day of the live action. I do not always have such a perspective view, but on this occasion, also given the exceptionality of the location, I had already decided that I would realise the work in two distinct, complementary moments: the action for house lights, which has to do with time, duration, and live experience; and the photographs, which instead invest the space, and break down that same duration into frames, visible both individually and as a whole. The image is thus a second step, as a further form of articulation of thought, a way of remaining, of making the idea exist not through a simple documentation of the action, but in a new, different, synthesis. Even though these are images, time remains the central element: Je m’appelle Olympia is a time-based photograhic work.

RSS: How does the installation at MAN dialogue with the original performance?

AG: I thought of the exhibition space as a small theatre, accessed through a red velvet curtain. The floor is also bright red, like the seats of Olympia. I tried to create an ’other’ space, suspended, removed from the interference of sounds or signs. The sixteen photographs, in a black frame and white background, all installed at the same height, flow on the walls, embracing the entire space, which is made up of three passing compartments. The only break, in one of the recesses, is a suspended display case presenting the score for the house lights’ action, and the small frame with the April 2012 invitation. Arriving at the back of the room, turning around, the spectator finds himself in front of a shut curtain, like the one in Paris. The circle is closed.

Je m’appelle Olympia is a project winner of the “PAC2021—Piano per l’Arte Contemporanea” program promoted by the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity of the Italian Ministry of Culture.

The exhibition, curated by Chiara Gatti, is on view at the MAN Museum in Nuoro until September 17, 2023.

Je m’appelle Olympia is also an artist’s book in leporello format, published by NERO.

Alice Guareschi (1976) is an Italian visual artist based in Milano. Over the years she has worked with a wide range of media, such as writing, sculpture, still images and video. Her work has been exhibited in museums, public institutions, private galleries and film festivals in Italy and abroad.